Written texts are an essential element of diplomacy. Texts provide powers and accreditation for the diplomat. Texts contain his instructions and negotiating briefs. Texts are the main outcome of negotiations. For certain texts – or parts of texts – there exist stereotyped formulas: letters of accreditation, full powers, opening and final clauses of treaties, even diplomatic notes. For all texts that are meant to be shared with another party or other parties, there are traditional requirements of polite formulations. On the other hand, internal documents only follow the rules of the entity which employs them. For countries long active in international diplomacy, there used to be all sorts of regulations regarding the writing of dispatches, instructions, briefs, reports, etc. New forms and means of communicating have affected the manner in which documents of diplomacy are written today, be they internal or addressed to one or more external entities.

Documents exchanged between countries in the past were written in the single vehicular language then in use in Europe: Latin. In the 18th century French had become the generally accepted diplomatic language, so much so that even diplomatic notes addressed to the British Foreign Office by the Legation of the USA were written in that language. The 20th century saw a gradual emergence of English as a second and later even dominant diplomatic language. At the same time, a growing number of countries insisted on the use of their own language in diplomatic correspondence and joint diplomatic documents. As a result the United Nations admitted to five languages at its inception (Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish), to which Arabic has later been added by informal agreement. In the European Union, all twelve languages of the members are currently in use and their number is bound to grow as new members will be admitted. Translation and interpretation have therefore become a major element in present-day diplomatic life.

In this presentation, we will consider the issues of formal diplomatic documents, multi-language diplomatic texts, and the impact of information technology on diplomatic texts.

FORMAL DIPLOMATIC DOCUMENTS

Full powers were traditionally given by a proclamation addressed to no one in particular. Until recently at least, even the foreign secretary of the British government was provided with such powers by the queen, although practice and the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961 have long admitted that a foreign minister, by virtue of his position, had all powers necessary to deal with foreign governments and to represent his government in international fora.

Letters of accreditation are always addressed to a specific destinatory, head of state or government, foreign minister, secretary-general of an international institution, etc. Their content is stereotyped, stating the full confidence of the accrediting actor in the accredited person and expressing the hope that the actor of accreditation will accord full credence to that accredited person. Full powers for specific purposes may be written in the same manner.

Diplomatic notes addressed by one entity to another had stereotyped beginnings and endings: XXX presents its compliments to YYY and has the honour to… XXX avails itself of this opportunity to renew to YYY the expression of its highest consideration. Each entity had to be presented with its full name, e.g. “The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of”. In the operative text, shorter mentions, in particular “the Ministry”, would be used. Courtesy of language had to be respected even if the subject-matter was a strong protest or the notification of a rupture. Today, in most notes much of the formality is omitted and the style used is more reminiscent of the Aide-Mémoire of yore. Even where an agreement is embodied in an exchange of notes, it is no longer required that each side fully reproduces the content. It is considered sufficient if the note containing the offer states all relevant clauses whereas the note expressing acceptance simply refers to the offer and then states the terms of acceptance.

Treaties used to be written with much formality as regards the opening and the final clauses. The title mentioned the parties (two or more) in full and this was followed by an introductory statement again mentioning the parties in full as well as their representatives by name and title. This was mostly followed by a preamble and only then came the substantive clauses. The content of the final clauses varied but the style remained formal. For bilateral treaties there were two originals; each mentioning one of the parties first and being initialled and signed by the representative of that party on the left side. These originals were exchanged. Today, many treaties use simplified titles and mention of parties and omit the names of representatives altogether except at the bottom of the last page where the signatures have to be affixed.

Consent to be bound by a treaty other than by signature used to be expressed in a very formal document, known as an instrument of ratification or of accession (in the case of participation in a multilateral treaty by a non-signatory). Instruments of ratification of a bilateral treaty contained the full text of the national version followed by the statement of ratification. In the case of multilateral treaties the instrument was a proclamation of ratification or accession in stereotyped terms. It was handed over to the depository of the treaty in a formal ceremony. More recently, expression of consent to be bound has also been expressed by notification using the form of a diplomatic note. This possibility must be indicated in the final clauses of the treaty. The advantage of this approach is particularly evident in bilateral treaties, where it replaces the exchange of instruments of ratification by duly empowered representatives, an exchange that has to be minuted. Notification of consent to be bound can be forwarded by a diplomatic mission or even by mail.

MULTI-LANGUAGE DOCUMENTS

Except between countries using the same national or vehicular language, diplomatic documents, these days, tend to be written in two or more languages. In bilateral relations a difference is made between authentic languages and unofficial translations. If two languages are both authentic, the interpretation problems have to be solved by reference to both. Unofficial translations on the other hand have no value of authenticity. Sometimes, the unofficial translation is in the language of one party which is not used in international relations. Thus Israel used to insist that an unofficial translation in Hebrew be attached to bilateral agreements for which English would be used for the Israeli version. China on the other hand insists that all diplomatic documents emanating from it be written in Chinese, but accepts that an unofficial translation into English be attached to them.

The writing of treaties in several languages is a complex task, especially if one or more of these languages are not used during the actual negotiation. Versions in working languages are based on the records of simultaneous interpretation. Versions in other languages have to be prepared separately. All have to go before the drafting committee which therefore needs at least one member for each language. Preferably however members of a drafting committee should master two or more of the languages used so as to ensure proper concordance of texts. The drafts submitted to the committee are prepared by the secretariat of the negotiating body, which must check recordings of simultaneous interpretation and produce versions in languages which were not used as working languages. The complexity of the task of a drafting committee explains why, in some cases, it will re-convene after the treaty has already been authenticated, with the express competence of making linguistic adjustments between the various versions.

Problems akin to those encountered with multilingual texts may arise with diplomatic texts negotiated and written in a single language when two or more countries are involved. For German speakers from Austria, Germany and Switzerland the same word may not have exactly the same meaning. This is even more pronounced among countries using English as a vehicular language, or Spanish, whereas in the case of French the meaning attributed by France tends to be generally accepted.

THE IMPACT OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

Information technology allows for working on a text which is displayed on computer screens or projected on a wall screen from a computer if the negotiation takes place in a conference room. This text can be directly amended, including by inserting versions in brackets on the display, or proposed amendments can be written into hypertext links. This last approach is particularly useful in multilateral negotiations conducted on the Internet, either in real time encounters or, even more, when negotiators can make their input in their own time and the secretariat from time to time sums up the situation.

The recourse to information technology is probably going to modify the presentation of bilateral agreements. These are likely to be written in a single version and no longer put down in two original documents. The lengthy mention of parties with their full names and the names of negotiators is likely to disappear. Consent to be bound may be expressed by notification over the Internet.

Multilateral treaties are always written in a single original, so recourse to information technology will not change anything in this regard. But ratification and accession can be notified over the Internet just as in the case of bilateral treaties.

Information technology is also likely to help with multilingual texts. There already exists software for translation, although this can at best produce a very rough draft that will have to be carefully edited. By working on texts accessible over the Internet, translators from various countries will be able to compare notes and thus help to produce better adjusted versions in the various languages of the treaty.

Information technology however also presents potential problems regarding the finalisation of an agreed text, in particular if this takes place over the Internet. Safeguards will have to be found to prevent a party from tampering with a finally agreed version.

SOME FINAL REMARKS REGARDING THE GENERAL IMPORTANCE OF LANGUAGE

We are living in a time when attention to good use of language tends to lapse. Media often use deplorable language, both spoken and written, and there is a definite danger that future diplomats will no longer master properly even their own mother tongue, let alone vehicular languages like English, French or Spanish. This will create additional difficulties in the implementation of existing agreements. As is well known, unclear language is often used to mask divergencies under the appearance of agreement. When these divergencies re-appear as a result of differing interpretation by the parties concerned, it is essential that those who may be entrusted with proposing solutions to such disputes fully master the language(s) concerned.

Information technology could provide help in solving insufficient mastery of languages. Interactive teaching can force the student to really grapple with the language he is learning and thus to achieve more than just superficial fluency. New texts negotiated with recourse to information technology can be better understood because all successive versions and the reactions to them remain documented. Hopefully this will lead to a newly enhanced linguistic culture in diplomacy.

You may also be interested in

Positive Diplomacy

The message details how positive diplomacy serves as an effective tool in building relationships and resolving conflicts between nations. It emphasizes the importance of mutual respect, cooperation, and understanding in diplomatic interactions for achieving peaceful resolutions and fostering international cooperation. Using positive communication and dialogue, countries can work together to address common challenges and build a more stable and prosperous global community.

Wilton Park: sui generis knowledge organisation

In his paper, Colin Jennings describes the way Wilton Park – an executive agency of the British FCO – operates. He highlights some of the key reasons for its success, and identifies some specific outcomes of the conferences organised by Wilton Park. The author also offers a few reflection on knowledge management based on his many years of experience.

ConfTech Help Desk: Frequently asked questions

The resource contains a list of commonly asked questions about the set-up of online meetings and conferences and the use of online conferencing tools.

The School for Ambassadors

The School for Ambassadors" is a fictional story about a school that trains individuals to become diplomats and navigate international relations. The main character, Simona, faces challenges and grows through her experiences, learning valuable lessons about diplomacy and personal growth. The story highlights the importance of communication, cultural awareness, and adapting to new environments in the field of diplomacy.

Dialogue-based Public Diplomacy: A New Foreign Policy Paradigm?

The text explores dialogue-based public diplomacy as a potential new foreign policy paradigm, analyzing its effectiveness and implications for diplomatic practice in contemporary international relations.

Australia’s Diplomatic Deficit: Reinvesting in Our Instruments of International Policy

The text discusses the importance of Australia re-investing in its instruments of international policy to address its diplomatic deficit.

Lessons from two fields

A conversation between a diplomat and an interculturalist, combining real-life examples from the diplomatic field with intercultural theory.

[GUIDE] Who should be on your organising team?

Human resources is a common issue among event organisers. The size of your organising team depends on the size of your event (and your budget).

Diplomatic Classics: Selected texts from Commynes to Vattel

The message will focus on highlighting the importance of classic diplomatic texts from Commynes to Vattel in understanding diplomatic history and principles, fostering a deeper comprehension of international relations.

The Queen’s Ambassador to the Sultan: Memoirs of Sir Henry A. Layard’s Constantinople Embassy, 1877-1880

Once more students of Ottoman diplomatic history are in debt to the scholar-publisher, Sinan Kuneralp, for Sir Henry Layard was one of the most remarkable and controversial of British ambassadors to Turkey in the nineteenth century and served there during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-8 – and yet the volumes of his memoirs dealing with this period have hitherto languished unpublished in the British Library, in part perhaps because of their size. (Layard admits himself to having been ‘somewhat minute, perhaps a great deal too much so’, p. 692.)They are here published almost in their entir...

Routledge Handbook of Public Diplomacy

The Routledge Handbook of Public Diplomacy explores the field's evolution, challenges, and strategies in the modern interconnected world. It investigates the role of both state and non-state actors in shaping international relations through communication and cultural exchange, emphasizing the importance of building relationships and understanding diverse perspectives for effective public diplomacy efforts.

The role of diplomatic missions in Open Government

The purpose of this research paper is to assess the degree to which Open Government values and principles are being implemented by the diplomatic missions of Moldova and Malta, particularly in regards to their work with civil society and citizens' participation in policy-making.

The inertia of Diplomacy

Diplomacy is used to manage the goals of foreign policy focusing on communication. New trends affect the institution of diplomacy in different ways. Diplomacy has received an additional tool in the form of the Internet. In various cases of interdependence and dependence interference in a country’s affairs is accepted. Multilateral cooperation has created parliamentary diplomacy and a new type of diplomat, the international civil servant. States and their diplomats are in demand to curb the excesses of globalization. The fight against terrorism also brought additional work for diplomac...

The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Diplomacy

Book by Geoff Berridge

[HOW-TO] How to use Jitsi for hosting an event

Jitsi is a set of open-source projects that enables users to create secure video conferences easily.

High Noon in Southern Africa: Making Peace in a Rough Neighbourhood

The text is about the challenges of achieving peace in Southern Africa amid regional conflicts and political instability.

Twitter for Diplomats

Twitter for Diplomats is not a manual, or a list of what to do or not to do. It is rather a collection of information, anecdotes, and experiences. It recounts a few episodes involving foreign ministers and ambassadors, as well as their ways of interacting with the tool and exploring its great potential. It wants to inspire ambassadors and diplomats to open and nurture their accounts – and it wants to inspire all of us to use Twitter to also listen and open our minds.

Diplomacy, international intervention and post-War Reconstruction

This paper focuses on interactions between states, international organisations and local authorities in the implementation of the Dayton Accords for Bosnia and Herzegovina. It stresses the importance of reassessing the very mechanism of functioning of the international community and its efforts for post-war reconstruction, including the issues of mutual cooperation, elaboration of existing structures and vision and perspective for the future.

A Selection of New diplomatic memoirs

I have just written a review article on these six books of British diplomatic memoirs for the English Historical Journal, so here I shall just provide some notes on those that I believe to be most valuable to students of diplomacy.

Do the Experts Mean What Their Metaphors Say? An Exploration of Metaphor in Mediation Literature

The message explores the use of metaphor in mediation literature to determine if experts truly align with what their metaphors suggest.

Philosophy of Rhetoric

The author introduces a series of Essays on Rhetoric, explaining their origins and interconnection. This work has been a lifelong pursuit since 1750 and is structured based on a plan laid out in the first two chapters.

Soft Power by Joseph Nye

In his book, Nye reminds us that many countries have "soft power" to different extents. Their origins are different, but they work the same way as the "U.S.'s soft power."

A Diplomat’s Handbook of International Law and Practice

The following text outlines guidelines for diplomats on international law and practice.

The Cinderella Service: British Consuls since 1825

The British Consul Service has evolved over the years since 1825, adapting to modern times while maintaining its traditional values and responsibilities.

Just a Diplomat

Close students of the new, Conservative Party Mayor of London, the at once engaging and alarming Boris Johnson, will know that he has Turkish cousins. One of these is Sinan Kuneralp, a son of the late Zeki Kuneralp, probably the most distinguished and well liked Turkish diplomat of his generation. Sinan Kuneralp is a scholar-publisher and runs The Isis Press in Istanbul, a house at the forefront of publishing scholarly works and original documents on the Ottoman Empire, chiefly in English and French. The three works noticed here are all its products and reflect the publisher’s own special in...

DiploDialogue – Metaphors for Diplomats

On Diplo’s blog, in Diplo’s classrooms, and at Diplo’s events, dialogues stretch over a series of entries, comments, and exchanges and may even linger. DiploDialogue summarises. It’s like in sports events: DiploDialogue aims to bring focus by deleting what, in hindsight, is less relevant. In this first DiploDialogue, Katharina Höne and Aldo Matteucci discuss the usefulness of analogies and metaphors for understanding international relations and diplomacy.

Language and Diplomacy: Preface

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): In the preface below, Jovan Kurbalija and Hannah Slavik introduce the chapters in the book, and extract the general themes covered by the various authors.

Diplomatic Reporting: No need to compete with media (CNN, BBC)

In the late 1990s, when Ambassador Nabil Fahmy became Egyptian ambassador in the United States, he decided to change diplomatic reporting from his embassy. Although it was in the early days of the Internet, most of his reasoning about diplomatic reporting is as relevant today as it was more than decade ago.

Visa Denial Diplomacy

The text discusses how diplomats can use visa denials as a diplomatic tool to express dissatisfaction or send a message to another country. It highlights that while visa denials can strain relations, they can also be a strategic way to convey disapproval or communicate diplomatic signals. Diplomats may utilize this tactic to convey a variety of messages to other nations, influencing their behavior or actions through the denial of visas.

On the proper use of violence: reflections on the fall of the Soviet Union

Professor Andre Liebich approaches the potential and limits of persuasion through the analysis of the use of coercion in political life. Two concepts – persuasion and coercion – are usually seen in binary way, as Dr Vella indicates in his article Persuasion is winning over by argument; coercion is subjecting by compulsion. Prof.

Diplomatenleben

A must-have for German-speaking students of Swiss diplomacy (and diplomacy generally) since the Second World War is Dr. Max Schweizer’s recently published Diplomatenleben.

Diplomats at War: British and Commonwealth diplomacy in wartime

In their Preface, the editors of Diplomats at War say that the two world wars in the twentieth century had a “catalytic impact upon the practice of diplomacy”; among other things, they continue, this produced “an unprecedented revolution” in the way heads of mission conducted their business.

Managing Global Chaos

The message deals with strategies for managing global chaos. It discusses the importance of adaptability, resilience, and communication in navigating turbulent international waters. Leaders are advised to anticipate challenges, foster collaboration, and maintain a proactive approach to addressing crises on a global scale. The text emphasizes the need for flexibility and innovation to effectively manage chaos in a rapidly changing world.

[HOW-TO] Comment utiliser Zoom pour organiser des réunions en ligne

La facilité d'utilisation de Zoom l'a mérité une place de choix parmi les plateformes en ligne les plus populaires au monde. Dans ce guide, nous vous montrons comment l'utiliser.

[HOW-TO] Comment participer à une réunion sur Zoom

Zoom est l'un des outils en ligne les plus populaires. Si vous êtes novice, voici un guide simple pour accéder à votre salle en ligne en Zoom.

[GUIDE] Livestreaming on social media platforms

The number of social media users has increased exponentially. By livestreaming your meeting on social media, you can scale your outreach.

Global health diplomacy: Advancing foreign policy and global health interests

Attention to global health diplomacy has been rising but the future holds challenges, including a difficult budgetary environment. Going forward, both global health and foreign policy practitioners would benefit from working more closely together to achieve greater mutual understanding and to advance respective mutual goals.

Prenegotiation and Mediation: The Anglo-Argentine Diplomacy after the Falklands/Malvinas War (1983-1989)

This paper studies the process of prenegotiation and the role of mediators during the negotiations between the Argentine and British governments about the dispute over the sovereignty of the Falkland/Malvinas Islands from immediately after the war of 1982 to 1990. In this period, the relationship between both governments evolved from rupture and no-relations to the agreement on the conditions to negotiate the renewal of full diplomatic relations concluded in early 1990. In a preliminary process of prenegotiation, the governments of Switzerland, initially, and the United States played a ro...

The Matrix of Face: An Updated Face-Negotiation Theory

The message provides an in-depth discussion on the updated Face-Negotiation Theory, titled "The Matrix of Face.

Diplomacy under a Foreign Flag: When nations break relations

The text is about diplomatic relations between countries and the implications of breaking these ties.

Persuasion, trust, and personal credibility

Ambassador Kishan Rana indicates the cultivation of relations and the credibility of diplomats as the basis for persuasion in diplomacy. He provides an initial taxonomy of the type of relations that diplomats should cultivate. When it comes to credibility, Ambassador Rana presents the main ways of developing and maintaining credibility in diplomatic relations. The more credible the diplomat, the more likely it is that their persuasion with local interlocutors will be successful.

The Evolution of Diplomatic Method

The Evolution of Diplomatic Method discusses the changing nature of diplomacy over time. From traditional methods to modern practices, diplomacy has adapted to technological advancements and global challenges. The article emphasizes the importance of evolving diplomatic strategies to effectively address the complexities of the contemporary world.

Byzantium and Venice: A study in diplomatic and cultural relations

This book traces the diplomatic, cultural and commercial links between Constantinople and Venice from the foundation of the Venetian republic to the fall of the Byzantine Empire. It aims to show how, especially after the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Venetians came to dominate first the Genoese and thereafter the whole Byzantine economy. At the same time the author points to those important cultural and, above all, political reasons why the relationship between the two states was always inherently unstable.

European Union external action structure: Beyond state and intergovernmental organisations diplomacy

This dissertation analyses the organisation of the external action structures of the European Union. As an international actor which is beyond a state, but also different to traditional international organisations, the EU has created a “diplomatic constellation” in which diplomacy from member states is not substituted but complemented by EU external action.

[HOW-TO] The 8 rules of conduct for online meetings

The online world has some unwritten but recommended rules of (good) behaviour. Keep them in mind when you're attending an online meeting or event.

The Permanent Under-Secretary of State: A brief history of the office and its holders

As the title of this booklet indicates, it is only a brief history of this increasingly influential office in the British Foreign & Commonwealth Office. Nevertheless, as one would expect from its provenance, it is completely authoritative, fluently written, draws on previously under-exploited archives, and includes many nineteenth century photographs never previously published.

Cyber-diplomacy: Managing Foreign Policy in the Twenty-first Century

Cyber-diplomacy: Managing Foreign Policy in the Twenty-first Century" discusses the importance of digital diplomacy in modern international relations. It explores how governments can leverage technology to engage with other countries, protect national interests, and navigate cyber threats effectively. This book offers insights into how cyber-diplomacy is reshaping traditional diplomatic practices and the key role it plays in shaping foreign policy in the digital age.

Persuading and resisting persuasion

Dr Alex Sceberras Trigona stresses that not only persuasion but also resisting persuasion is highly important for small states, which tend to be seen as the ‘diplomatic prey’ of great powers. He analyses three examples of successful persuasion from Maltese diplomatic history. First were the negotiations on Maltese neutrality, which required a lot of persuasion of two major Cold War powers and numerous regional players in the Mediterranean.

Virtual Reality and the Future of Peacemaking (Briefing Paper #14)

The briefing paper discusses the potential of virtual reality in fostering peacebuilding efforts worldwide. Through VR technology, individuals can develop empathy, understand different perspectives, and communicate effectively, facilitating conflict resolution. VR applications can simulate real-life scenarios, promote dialogue, and reduce prejudice by experiencing situations from another's point of view. This innovative approach has the potential to enhance peacebuilding initiatives and create a more connected and understanding global community.

The Work of Diplomacy

The message explores the importance and intricacies of the diplomatic process, emphasizing its pivotal role in negotiating peace, resolving conflicts, and fostering international relationships. Diplomacy requires skill, tact, and strategy to navigate complex political landscapes effectively, ultimately aiming to promote stability and cooperation between nations.

EU Turkey negotiations: Obstacles to Turkey’s application to join the EU

Turkey’s accession to the European Union is one of the most controversial topics the EU faces. There is a division both between EU Politicians and European citizens about Turkey’s accession to the EU. For a number of factors, the Turkish application has not been perceived by the EU in the same way as other applications. In fact, various Chapters are blocked due to the uneasy relationship which exists between Turkey and some EU Member States.

South Africa, the Colonial Powers and ‘African Defence’: The rise and fall of the white entente, 1948-60

This book describes the fate of South Africa's drive, which began in 1949, to associate itself with Britain, France, Portugal and Belgium in an African Defence Pact. It describes how South Africa had to settle for an entente rather than an alliance, and how even this had been greatly emasculated by 1960. In light of this case, the book considers the argument that ententes have the advantages of alliances without their disadvantages, and concludes that this is exaggerated.

All Fall Down: America’s fateful encounter with Iran

All Fall Down is the definitive chronicle of Americas experience with the Iranian revolution and the hostage crisis of 1978-81. Drawing on internal government documents, it recounts the controversies, decisions and uncertainties that made this a unique chapter in modern American history. From his personal experiences, the author draws revealing portraits of the people who engaged in this test of wills with an Islamic revolutionary regime.

Amarna Diplomacy: The Beginnings of International Relations

The text discusses the emergence of diplomatic relationships during the Amarna period, highlighting how this era marked the start of international relations.

Diplomacy and Power: Studies in Modern Diplomatic Practice

The text explores the complex relationship between diplomacy and power, analysing their interconnectedness and interactions on the global stage.

The Role of Nigeria in Restoring Peace in West Africa

Remmy Nweke attempts a search into the rationale behind Nigeria‟s decision to make Africa the cornerstone of her foreign policy.

The Death of Ambassador Chris Stevens, the Need for ‘Expeditionary Diplomacy,’ and the Real Lessons for U.S. Diplomacy

The text discusses the death of Ambassador Chris Stevens, emphasizes the necessity of "Expeditionary Diplomacy," and highlights key lessons for U.S. diplomacy.

Persuasion

In "Persuasion", the protagonist, Anne Elliot, faces societal pressures and second chances as she navigates love and relationships. This classic novel by Jane Austen explores themes of social class, family dynamics, and the consequences of past decisions on one's future. Anne's character development and resilience in the face of adversity are central to the story, making it a timeless tale of love, perseverance, and personal growth.

Intractable Syria? Insights from the Scholarly Literature on the Failure of Mediation

The article discusses the challenges and reasons behind the failure of mediation efforts in Syria based on scholarly literature.

Under the Wire: How the Telegraph Changed Diplomacy

Review by Geoff Berridge

Diplomacy: The world of the honest spy

In a world of diplomacy, honesty is key even for spies.

The New Diplomacy

Shaun Riordan was a British diplomat for 16 years before resigning in 2000 to take up private consultancy work and journalism in Spain, where he had ended his diplomatic career as political officer in the embassy. He has written a conceptually flawed, often vague, sometimes contradictory, and essentially polemical attack on 'traditional diplomacy'. It is also peppered with New Labour jargon ('stakeholders', 'global governance', 'civil society'), has its fair measure of superficially examined mantras, misquotes Clausewitz, and sports a shop-soiled title - is he not aware that Abba Ebban publish...

Persuasion through negotiation at the Congress of Vienna 1814-1815

Dr Paul Meerts discusses persuasion in the context of the Vienna Congress (1814–1815), one of the most successful diplomatic events in history. The Vienna Congress created long-lasting peace and set the basic rules of multilateral diplomacy and protocol. Dr Meerts’s paper focuses on how the Vienna Congress addressed one of the main challenges of any negotiations: the more actors you have around the table, the less effective those negotiations are.

Tech Diplomacy: Actors, Trends, and Controversies

In today’s world, tech diplomacy bridges governments and tech companies, focusing on governance, policy, and cooperation in digital technologies and AI. This publication examines its definition, relevance, key actors, methods, and global hubs. It builds on prior reports and highlights Denmark’s pioneering efforts in establishing a dedicated tech diplomacy policy.

[GUIDE] Using FOSS platforms for your online meetings

Free and open source software (FOSS) platforms are a great option for those who prefer a tool developed in a collaborative and public manner.

Conflict resolution and peace building (disseration by Unisa Sahid Kamara)

Unisa Kamara's dissertation seeks to give an account of the Sierra Leone conflict and the different measures and strategies including diplomatic attempts and efforts that were employed by various parties in trying to secure a peaceful and durable solution to it. The paper discusses the peace building measures and activities that were employed in sustaining the Sierra Leone peace process after the attainment of a negotiated settlement.

Message on Switzerland’s International Cooperation in 2013-2016

The text discusses Switzerland's international cooperation activities from 2013 to 2016.

Regional water cooperation in the Arab – Israeli Conflict: A case study of the West Bank

The conflict between Israel and Arab countries, with several devastating wars, is about territory and land, and maybe just as crucially on the water that flows through that land. This dissertation, an analysis of the management of water in the West Bank, as a case study, seeks to underline the possibility of using soft power diplomacy, in addition to mediation and water cooperation, for a more collaborative kind of approach to the conflict.

Language and Power

The text discusses the relationship between language and power, highlighting how language can be used to manipulate and control individuals and societies. It explores how those in power often dictate the norms and values through language, influencing perceptions and behaviors. The text also emphasizes the importance of recognizing and challenging power dynamics embedded in language to promote equality and social change. Language is portrayed as a tool that can both reinforce and challenge power structures within a society.

Talking to Americans: Problems of language and diplomacy

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): Professor Paul Sharp discusses negotiation with American mediators. He notes that most literature on negotiation is written to advise Americans and other Westerners about negotiating with foreigners.

Beyond diplomatic – the unravelling of history

In his paper, Robert Alston travels through time to rekindle an important highlight – as well as a personal highlight – in the history of knowledge management. His journey takes him back to the 1850s, which saw Antonio Panizzi’s efforts in creating a universal repository of knowledge in the British Museum; and to the 1990s, a time in which he acquired first-hand experience at the same museum, drawing conclusions on the various available ways of navigating large bibliographical and archival databases.

Framing an argument

Dr Biljana Scott’s article on framing an argument introduces the linguistic and rhetoric aspects of persuasion. The way in which we frame an issue largely determines how that issue will be understood and acted upon. By dissecting Obama’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech of December 2010, Dr Scott illustrates the main techniques for framing an argument.

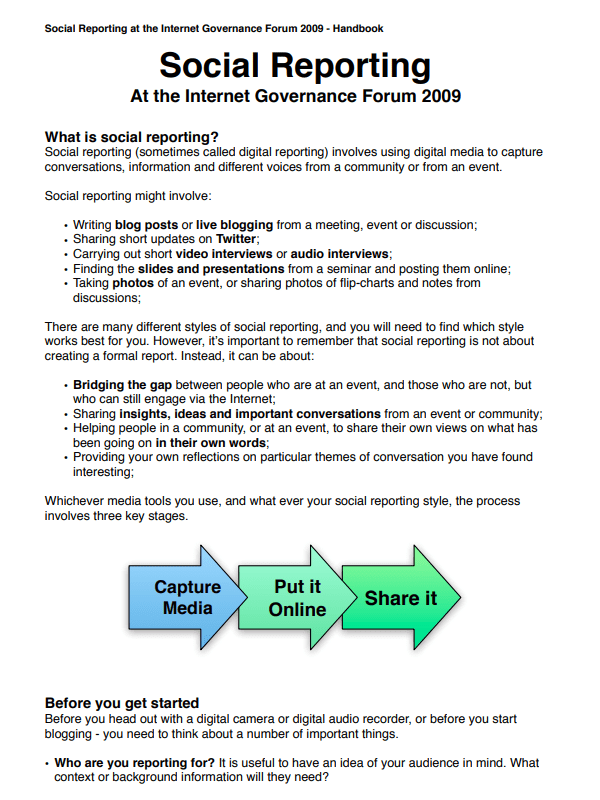

Handbook on Social Reporting

A Social Reporting Handbook was created in response to the growing trends and needs of E-participation during important global and regional policy forums: it provided useful guidance on what social reporting is, why it is needed, and how to report from the events. The international and regional policy forums are not only taking place inside conference centres, but also across the world via Internet tools such as remote participation and social media. It is important to help involve professionals to embrace social media tools in order to extend their personal and institutional capabilities to l...

The International Climate Change regime: A Guide to Rules, Institutions and Procedures

The International Climate Change regime is a comprehensive guide that outlines the rules, institutions, and procedures related to addressing climate change on a global scale.

Keeping the Peace in the Cyprus Crisis of 1963-64

After some difficulties, a UN force was established in Cyprus (UNFICYP) following the collapse of the bicommunal independence constitution of this former British colony - a constitution which the Greek Cypriots had always felt too favourable to the Turkish minority - at Christmas 1963. In this book, Alan James, Professor Emeritus of Keele University and leading authority on peacekeeping, provides what is likely to be regarded as the definitive history of the creation of this force.

Persuasion as a social phenomenon

Aldo Matteucci explores the relevance of social context for persuasion. Since persuasion leads to change, we should look into the mechanisms of change in society. Change is a social phenomenon. Change occurs when the intentionalities of individuals transmute into ‘collective intentionalities’. In this process, enablers play a key role.

Action-Forcing Mechanisms

The message following this prompt will discuss the concept of Action-Forcing Mechanisms, which are tools or processes designed to prompt individuals or organizations to take specific actions or make decisions within a certain timeframe. These mechanisms are often put in place to ensure accountability, compliance with regulations, or timely responses to important issues.

How the ‘inscrutables’ negotiate with the ‘inscrutables’: Chinese negotiating tactics vis-à-vis the Japanese

I had the opportunity to participate in the five major negotiations between China and Japan from 1972 to 1975 (i.e., the talks over the normalization of diplomatic relations, and the aviation, trade, shipping and fishery agreements), and to observe the tactics, both offensive and defensive, used by the Chinese participants. Personal impressions are bound to be biased, but fortunately there are at least two books which give us detailed accounts of negotiations between China and Japan in the post-war period. These are The Record of Fishery Talks between China and Japan and The Secret Memorandum ...

21st Century Diplomacy: A practitioner’s guide

Kishan Rana is a man of lengthy and varied experience in the Indian Foreign Service, ending his career as ambassador to Germany. Since then he has spent many years as a globe-trotting trainer of junior diplomats on behalf of DiploFoundation. Few people, therefore, are as well placed to write a practitioners’ guide to the diplomatic craft; and, insofar as concerns the content of his book, which can be found described here, he has not disappointed.

Interplay between Telecommunications and Face-to-Face Interactions: A Study Using Mobile Phone Data

The study explores the relationship between telecommunications and face-to-face interactions using mobile phone data.

Language and negotiation: A Middle East lexicon

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): Professor Raymond Cohen writes that "when negotiation takes place across languages and cultures the scope for misunderstanding increases. So much of negotiation involves arguments about words and concepts that it cannot be assumed that language is secondary." With numerous examples of the culturally-grounded references, associations and nuances of certain words and phrases in English and the Middle Eastern languages (Arabic, Turkish, Farsi and Hebrew), Cohen introduces his project of developing a negotiating lexicon of the Middle East as a guide for condu...

The Internet and diplomats of the 20th century

The Internet and diplomats of the twenty century: how new information technologies affect the ordinary work of diplomats.

Diplomacy by other means

Diplomacy by other means

In Confidence: Moscow’s Ambassador to Six Cold War Presidents

The book "In Confidence: Moscow's Ambassador to Six Cold War Presidents" gives an inside look at diplomatic relations during the Cold War by sharing the experiences of Moscow's ambassador to the United States.

Back Channel to Cuba: The hidden history of negotiations between Washington and Havana

This book went to press after the much-publicised handshake between US president Barack Obama and Cuban president Raul Castro at the memorial service for Nelson Mandela in December 2013 – but before their historic, simultaneous announcements a year later, assisted by a prisoner exchange and the good offices of the Vatican, that they were resolved to end their 50 years of estrangement and normalise relations.

Modernising Dutch Diplomacy

The Dutch government is making investments in the modernization of its diplomatic services to enhance its efficiency, effectiveness, and digital capabilities. This upgrade aims to position the Netherlands as a leader in global diplomacy by adapting to the changing international landscape and embracing innovation.

Camp David: Peacemaking and Politics

The Camp David Accords were pivotal in bringing peace between Israel and Egypt, mediated by President Carter in 1978, despite challenges and initial reluctance. This historic agreement demonstrated the value of diplomatic efforts and personal relationships in resolving conflicts.

The Office of Ambassador in the Middle Ages

The text discusses the role and responsibilities of an ambassador in the Middle Ages. It touches upon the importance of diplomatic skills, cultural awareness, and the power dynamics involved in representing a kingdom or ruler in foreign territories. The text emphasizes the ambassador's role in negotiation, communication, and fostering positive relationships to advance their country's interests.

The Roads from Rio: Lessons Learned from Twenty Years of Multilateral Environmental Negotiations

The text discusses key lessons learned from two decades of multilateral environmental negotiations, emphasizing insights gained since the Rio conference.

Ripeness theory and the Oslo talks

The text discusses the relevance of ripeness theory in the context of the Oslo talks.

Last Man Standing: Memoirs of a political survivor

Jack Straw was the ablest and wisest of Tony Blair’s foreign secretaries and served in this capacity from 2001 until he was ungratefully dumped without warning by his leader in 2006. Afterwards he hit the headlines by courageously publishing his dislike of the full veil worn my some Muslim women, on the grounds that this was such a visible statement of separation and difference that it complicated community relations and was, in any case, a cultural preference rather than a religious obligation. (Straw was then and still is the Labour MP for a Bradford constituency with a large Muslim popula...

Foreign Ministries: Managing Diplomatic Networks and Optimizing Value

This is a collection of papers presented at the 2006 Conference on Foreign Ministries hosted by DiploFoundation in May 2006, in Geneva. The overarching theme is the adaptation and reform that these ministries have undertaken, in the shape of country experiences and the transformation implemented in specific areas such as the application of information technology for outreach to domestic publics, adaptation in consular services and outsourcing options. Some of the challenging issues addressed cover relations between civil servants and politicians, the role of sub-state entities in diplomacy, an...

Cyprus: the search for a solution

Lord Hannay, a senior British diplomat with great experience of multilateral diplomacy, retired in 1995 but was then persuaded to accept the position of Britain’s Special Representative for Cyprus. In this role he played an influential part in the UN-led effort to broker a settlement to the Cyprus conflict until the negotiations temporarily foundered in May 2003, when, with a mixture of relief and regret, he stepped down. (There is a postscript on the referendums held on the island in 2004 on the fifth version of Kofi Annan’s settlement plan.) He has written a brilliant account of the cour...

[GUIDE] An in-depth survey of online meeting platforms

Your starting point to choosing the right platform is: how many people will connect to my meeting or event? Or how much will I have to pay for my monthly subscription? If you're organising several meetings, or in charge of your organisation's events, you might consider a mix of platforms. Keep your options open to ensure maximum flexibility.

International Diplomacy Volume I: Diplomatic Institutions

The message provides information related to international diplomacy found in "International Diplomacy Volume I: Diplomatic Institutions.

Enhancing Global Governance: Towards a New Diplomacy

The text is about the importance of improving global governance through a new approach to diplomacy.

Diplomacy for the New Century

The text discusses the importance of diplomacy in the modern era, emphasizing the need for updated approaches and strategies in international relations. Diplomacy plays a crucial role in addressing global challenges and fostering cooperation among nations in the 21st century.

The UN and the world diplomatic system: lessons from the Cyprus and US- North Korea talks

In Bourantonis, D. and M. Evriviades (eds), A United Nations for the Twenty-First Century(Kluwer Law International, 1996), pp. 105-16

[HOW-TO] How to use Join.me for hosting an event

Join.me is a user-friendly video conferencing platform that allows users to connect to video calls by phone or internet (VoIP).

Leaders’ rhetoric and preventive diplomacy – issues we are ignorant about

In this paper, Drazen Pehar analyses the argumentation made by George Lakoff of the University of California at Berkeley in his seminal paper on ‘Metaphor and War’, in which he tried to deconstruct the rhetoric U.S. president George Bush used to justify the war in the Gulf. He also analyses a reading by psycho-historian Lloyd deMause, whose theory differs from Lakoff’s. Throughout his analysis, Pehar describes the role of rhetoric in diplomatic prevention of armed conflicts, and its several functions, and concludes that the methods of preventive diplomacy depend heavily on the theory of...

Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion

Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion" explores the principles of influence and persuasion, delving into why people say yes to requests. Through research and examples, it sheds light on the factors that influence decision-making and offers insights on how to navigate these tactics in everyday interactions. Understanding these principles can help individuals become more aware of subtle persuasion techniques and make more informed choices in various situations.

The Ambassadors and America’s Soviet Policy

The Ambassadors and America's Soviet Policy discusses the roles of three prominent American ambassadors in shaping U.S. policy towards the Soviet Union during the early Cold War period. These diplomats employed various strategies to navigate the complexities of Soviet-American relations, including engaging in diplomacy, intelligence gathering, and negotiation. Overall, their efforts helped influence U.S. foreign policy towards the Soviet Union and contributed to the eventual end of the Cold War.

The Search for Peace

The text discusses the importance of seeking peace within oneself and in the world around us. It emphasizes the impact of personal inner peace on creating a harmonious environment globally. The text suggests that by finding peace within ourselves, we can contribute to fostering peace on a larger scale.

Negotiating across cultures

The text is about the importance of understanding cultural differences in negotiations. It highlights the need for awareness of varying communication styles, etiquette, and values when engaging in cross-cultural negotiations. By acknowledging and respecting cultural nuances, negotiators can build trust, establish rapport, and achieve successful outcomes in diverse settings.

Ambiguity versus precision: The changing role of terminology in conference diplomacy

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): Of central concern in the field of negotiation is the use of ambiguity to find formulations acceptable to all parties. Professor Norman Scott looks at the contrasting roles of ambiguity and precision in conference diplomacy. He explains that while documents drafters usually try to avoid ambiguity, weaker parties to an agreement may have an interest in inserting ambiguous provisions, while those with a stronger position or more to gain will push for precision.

Pragmatics in diplomatic exchanges

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): Edmond Pascual interprets diplomatic communication with the linguistic tools of pragmatics. He begins by reminding us that while the diplomat is a "man of action," the particular nature of the diplomat's action is that it consists of speech. Pascual applies three concepts of pragmatics to diplomatic discourse: speech as an intentional act; the effects of the act of speech; and the role of the unsaid in the act of speech.

German Strategy for International Digital Policy

The German government's Strategy for International Digital Policy outlines their commitment to safeguarding democracy and freedom online, promoting human rights, advocating for a global, open, free, and secure internet, enhancing technology partnerships, supporting cross-border data flows, shaping international standards, ensuring sustainable and resilient digital societies, and utilizing digitalization to address global challenges. This strategy aligns with various policy goals and emphasizes the importance of cooperation at global, regional, and national levels to advance digital governance,...

[HOW-TO] How to use the Mentimeter app in Zoom

Mentimeter has recently become available in the Zoom Marketplace, making it easier to use during online meetings. Mentimeter is an online voting tool that enables more effective and interactive meetings. You can use this powerful combination of Zoom and Mentimeter together whilst remote working or distance teaching. Mentimeter integrated into Zoom enables live polls, live brainstorming, engaging whiteboards, or simple voting. This encourages participants to engage and interact with the session.

Documenting diplomacy, Evaluating documents: The case of the CSCE

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): Rather than individual documents, Dr Keith Hamilton looks at the process and purpose of compiling collections of documents. He focuses on his own experience as the editor of Documents on British Policy Overseas, and particularly on his work publishing a collection of documents concerning the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe from 1972 until 1975.

Peace Negotiations and Time: Deadline Diplomacy in Territorial Disputes

The text discusses the importance of time in peace negotiations for territorial disputes, emphasizing how deadlines can impact diplomacy and the need for effective time management in reaching agreements.

Getting to the Table: The Process of International Prenegotiation

The discussed text focuses on the process of international prenegotiation, highlighting the importance of understanding the dynamics and relationships between parties before formal negotiations begin.

The Expert Negotiator: Strategy, Tactics, Motivation, Behaviour and Leadership

The key points on negotiation strategies, tactics, motivation, behavior, and leadership are covered in the book "The Expert Negotiator." It provides valuable insights and guidance on enhancing negotiation skills.

Persuasion, the Essence of Diplomacy

This journey through persuasion in diplomacy was initiated by Professor Kappeler’s long experience in both practicing diplomacy and in training diplomats.

Politics Among Nations

The text "Politics Among Nations" discusses the nature of international relations, emphasizing the importance of power and national interests in shaping diplomatic interactions. It explores the role of diplomacy and military endeavors in maintaining stability and resolving conflicts on a global scale. "Politics Among Nations" delves into the complexities of state behavior and strategic decision-making within the framework of the international system.

This Side of Peace: A Personal Account

This Side of Peace: A Personal Account" provides an insightful narrative detailing personal experiences related to peace.

Secret Channels: The Inside Story of Arab-Israeli Peace Negotiations

Secret Channels: The Inside Story of Arab-Israeli Peace Negotiations" delves into the clandestine negotiations that paved the way for peace agreements between Arab nations and Israel. It provides insight into the complexities, challenges, and breakthroughs that occurred during these diplomatic efforts, offering a behind-the-scenes look at the intricate process of brokering peace in the Middle East.

Health, security and foreign policy

Over the past decade, health has become an increasingly important international issue and one which has engaged the attention of the foreign and security policy community. This article examines the emerging relationship between foreign and security policy, and global public health. It argues that the agenda has been dominated by two issues – the spread of selected infectious diseases (including HIV/AIDS) and bio-terror. It argues that this is a narrow framing of the agenda which could be broadened to include a wider range of issues. We offer two examples: health and internal instability,...

Journeying Far and Wide: A Political and Diplomatic Memoir

Kaiser was an active Democrat and 'noncareer officer' in the US Foreign Service under three Democratic presidents: Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter. His memoir, which is uncluttered with the trivial detail sometimes found in this genre and written with great verve, will be valued by diplomatic historians of the whole period since the Second World War. (Kaiser had served earlier as Assistant Secretary of Labor for International Affairs in the Truman administration.)

Governance and conflict in the Mano River Union States: Sierra Leone a case study

The MRU states (Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone) experienced more than two decades of bitter conflicts. With the exception of Guinea which was spared a full-scale civil war, the other three neighbouring MRU states went through violent civil conflicts which resulted in massive human suffering, social dislocation and the destruction of the region's economy.

Peacemaking 1919

The message examines the peacemaking efforts of 1919, reflecting on the challenges faced during the time and lessons learned from the process.

[HOW-TO] How to use UberConference for hosting an event

This guide will provide basic information on the use of UberConference video communication platform.

Getting Our Way: 500 Years of Adventure and Intrigue: The Inside Story of British Diplomacy

The message summarizes the book "Getting Our Way: 500 Years of Adventure and Intrigue: The Inside Story of British Diplomacy.

Diplomacy for a Crowded World

The message emphasizes the importance of diplomacy in a world facing increasing population growth and competition for resources. Diplomacy is portrayed as a crucial tool for navigating the complexities of a crowded world, fostering cooperation, and finding peaceful solutions to global challenges.

Frontline Diplomacy: The U.S. Foreign Affairs Oral History Collection on CD-ROM

The ADST is a private, non-profit organization whose mission is ‘to spread knowledge about the practice and history of modern American diplomacy’. To this end, its Oral History Project, created in 1985 under the direction of former Consul-General Stuart Kennedy, has devoted considerable resources to conducting, recording, and editing interviews with retired members of the US Foreign Service, among others.

On Behalf of My Delegation,…: A Survival Guide for Developing Country Climate Negotiators

The one hundred pages of this book are in fact a useful Survival Guide for those approaching climate change negotiations for the first time. It has been written for developing country delegates, but delegates from other countries can also profit from its reading the same way that a similar survival guide for industrialized country delegates would be useful for those coming from developing countries, because it is necessary to know both sides of the story

Secret, lies and diplomats

The text discusses confidential conversations between diplomats including secrets and falsehoods.

Bertie of Thame: Edwardian Ambassador

Explore the life of Bertie of Thame, an Edwardian ambassador, to gain insights into his diplomatic achievements and the impact he had on international relations during his time.

Inside Diplomacy

This is a book on diplomacy in general and the Indian Foreign Service (IFS) in particular. It is also a gem, and a large gem. It breathes life, wisdom, and good humour, and is full of rich detail. I found it thoroughly absorbing. Students of diplomacy at all stages of their careers will find it immensely useful, while those in a position to influence the future shape of the IFS will discover a whole raft of constructive suggestions for reform fearlessly advanced.

The Demilitarization of American Diplomacy: Two cheers for striped pants

The trenchant contribution to this subject of the outstanding American scholar-diplomat Laurence Pope is published in Palgrave’s ‘Pivot’ series of short books designed to be brought out quickly.

Diplomatic Security under a Comparative Lens – Or Not?

“Diplomatic security” is the term now usually preferred to “diplomatic protection” for the steps taken by states to safeguard the fabric of their diplomatic and consular missions, the lives of their diplomatic and consular officers, and the integrity of their communications; it has the advantage of avoiding confusion with the controversial legal doctrine of diplomatic protection.

Diplomacy and Journalism in the Victorian era: Charles Dickens, the Roving Englishman and the “white gloved cousinocracy”

The Victorian era saw the convergence of diplomacy and journalism, with figures like Charles Dickens embodying this relationship. Dickens, known as the Roving Englishman, navigated political and social landscapes, shedding light on the "white gloved cousinocracy" of the time.

Twentieth-Century Diplomacy: A Case Study of British Practice, 1963-1976

Some years ago, John Young, Professor of International History at the University of Nottingham and long-serving Chair of the British International History Group, turned his thoughts and research in the direction of diplomatic procedure. This is the first monograph to be the product of his shift in direction and it is to be most warmly welcomed. It is original in focus, impeccably researched (private papers and oral history transcripts have been sifted as well official documents in The National Archives), crisply written, and altogether a major contribution to the contemporary history of diplom...

Global Health Diplomacy: Concepts, Issues, Actors, Instruments, Fora and Cases

The message provides information on global health diplomacy, covering concepts, issues, actors, instruments, fora, and cases.

Years of Upheaval

The text discusses the challenges and changes experienced over several years.

On the importance and essence of foreign cultural policy of states

Foreign cultural policy is in itself vital for establishing long lasting and deep relations between countries in international intercourse. But what we should equally bear in mind is that it is important to preserve the variety and the diversity of cultures in our efforts to bring about global cultural communication. Uniform culture is not culture and cannot be communicated.

The Yugoslav diplomatic service under sanctions

Sanctions adversely affect all the structures of the state and society, and render difficult, if not impossible, the normal operation of services, including the Foreign Service.This paper discusses the challenges faced by the Yugoslav diplomatic service when the country was under sanction.

Persuasion as the step towards convergence in negotiations

Ambassador Victor Camilleri argues that the essence of diplomacy is a search for a point of convergence. Persuasion is one of the methods through which a point of convergence can be reached. He gives central relevance in diplomacy to the firm grasp of the essential points of negotiation, including assessment of balance of force. This article analyses persuasion in multilateral diplomacy through a case study the Maltese initiative on the ‘Common heritage of mankind’.

[HOW-TO] How to use Mozilla Hubs for hosting an event

Hubs is a place where you can meet people in a 3D environment.

A Dictionary of Diplomacy

Like all professions, diplomacy has spawned its own specialized terminology, and it is this lexicon which provides A Dictionary of Diplomacy's thematic spine. However, the dictionary also includes entries on legal terms, political events, international organizations and major figures who have occupied the diplomatic scene or have written influentially about it over the last half millennium. All students of diplomacy and related subjects and especially junior members of the many diplomatic services of the world will find this book indispensable.

Essence of Diplomacy

Christer Jönsson is Professor of Political Science at Lund University in Sweden, where Martin Hall is a Researcher. Their book is described as an exercise in ‘theorizing’ diplomacy, that is, an attempt to provide a general account of its causes and consequences. (The authors are thus severe in denying the title of ‘theory’ to the ‘prescriptive tracts’ which scholar-diplomats have written about their art over hundreds of years, though I notice that they are more indulgent to the use of the term ‘political theory’ as in, for example, ‘liberal political theory’.)

I’ll be with you in a Minute Mr. Ambassador: The Education of a canadian Diplomat in Washington

The message shares insights from the book "I'll be with you in a Minute Mr. Ambassador: The Education of a Canadian Diplomat in Washington.

Theatre of Power: The Art of Signaling

Theatre of Power: The Art of Signaling discusses how strategic signaling plays a vital role in navigating power dynamics. Leaders can use various techniques to convey strength and influence, such as body language, attire, and other symbols. Mastering the art of signaling can help individuals assert dominance and command respect in various settings.

To End a War

The text is about the importance of peace negotiations as a way to end a war, highlighting the complexity and challenges involved in reaching a resolution through dialogue and compromise. It emphasizes the need for both parties to prioritize understanding and cooperation in order to achieve a lasting peace.

Equity and state representations in climate negotiations

The text examines the dynamics of equity and state representations within climate negotiations, highlighting the complexities and challenges of addressing fairness and inclusivity in global climate governance.

The origins – where is the connection between persuasion and rhetoric?

As ancient rhetoricians believed that language was a potent force for persuasion, they insisted that their students develop copia in all spheres of their art. Copia denotes an abundant and ready supply of language in any situation that arises. Why did ancient teachers of rhetoric insist on this practice? Well, they knew that training their students in different rhetorical arts prepared them for the multitude of communicative and persuasive possibilities that exist in language.

True Brits: Inside the Foreign Office

True Brits: Inside the Foreign Office" offers an in-depth look into the workings of the British Foreign Office, shedding light on the complexities of international relations and diplomacy.

The geopolitics of access to oil resources: The case of Uganda

Ten years ago, Uganda joined other sub-Saharan African Countries with new discoveries of oil; and just as the case always is, this news comes with high prospects for development and economic transformation. These ambitious projections are always based on the success stories of oil money in other countries without prejudice to the fear of the infamous oil curse that results from poor exploitation of oil revenues. With these aspirations at hand, Uganda has clearly stated in its national polices and development plans the fact that the country's development in the next 30 years shall be largely de...

The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy

The message provides information on modern diplomacy from The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy.

Diplomacy with a Difference: The Commonwealth Office of High Commissioner, 1880-2006

Book review by Geoff Berridge

Reflections on Persuasion in Diplomacy by Ambassador Joseph Cassar

In our families, in our jobs, in our political dynamic at a national level, we always try to persuade others, first and foremost. Since, diplomacy is part of the global human existence, it is natural that persuasion is an essential part and an essential tool of diplomacy … as much it is in your family life, in my family life, when you try to sort out trouble within your family, between your brothers and sisters, between your children and between your grandchildren at my age.

English Medieval Diplomacy

The text discusses English Medieval Diplomacy.

British Envoys to Germany 1816-1866

The text discusses the role and activities of British envoys in Germany from 1816 to 1866.

Brian Barder’s Diplomatic Diary

Sir Brian Barder, the senior British diplomat and author of the always sage and sometimes gripping What Diplomats Do, died in 2017 but, courtesy of the professional editorial hand of his daughter Louise, has left us another treat. This is what he called a diary and which for the most part has the form of a diary (dated daily entries), although originally it was a series of letters sent to friends from foreign parts. Compared to diplomatic memoirs, diplomatic diaries are a rarity. And since this one is the product of an acute observer who loved the English language and used it in a vigorous and...

The impact of the Internet on diplomatic reporting: how diplomacy training needs to be adjusted to keep pace

Over the last 20 years, the Internet has changed the ways in which we work, how we socialise and network, and how we interact with knowledge and information.

Don’t Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate

In "Don't Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate," the author emphasizes the importance of understanding values and framing in shaping debates effectively.

The Foreign Office

This book contains a comprehensive description of the British Foreign Office and the Foreign Service since the important Eden reforms of 1943.

Making Foreign Policy: A Certain Idea of Britain

In the course of his distinguished diplomatic career Sir John Coles worked in the Cabinet Office and was Private Secretary to the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher. At the time of his retirement in 1997 he was concluding over three years as Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office. His views on the problems now faced by British foreign policy-making and what might be done to correct them, which it is the main object of this book to present, thus demand close attention.

Le code du travail burkinabé face au télétravail: Comment adapter le code du travail burkinabé pour qu’il réponde aux exigences du travail à distance?

Les TICs et l’Internet particulièrement ont étouffé le fondement de la nécessaire présence physique du travailleur dans l’entreprise. Au Burkina Faso, ce contexte a créé de nouvelles opportunités dont le travail à distance, depuis l’accession du pays au cyberespace en 1996.

The Embassy: A story of war and diplomacy

This book tells the story of the vital role played by the US Embassy in Monrovia in helping to mediate an end to the brutal, 14-year civil war in Liberia in 2003.

From U Thant to Kofi Annan: UN Peacemaking in Cyprus, 1964-2004

2004 marked the fortieth anniversary of the United Nations presence in Cyprus. Since March 1964, the UN has been responsible for addressing and managing both peacekeeping and peacemaking efforts on the island.

[GUIDE] How to set up your online conferencing presentation

This tutorial will help you set up the scene, lighting, camera, and audio in your home office or studio environment for the optimal videoconference experience.

[HOW-TO] How to use Wonder for hosting an event

Wonder is a video communication platform that allows for larger online group gatherings that mirror on-site meetings.

Multilateral Conferences: Purposeful International Negotiation

The message will provide insights on the purpose and significance of multilateral conferences in facilitating international negotiations.

Digital Diplomacy as a foreign policy statecraft to achieving regional cooperation and integration in the Polynesian Leaders Group

Established in 2011, the Polynesian Leaders Groups serves to fulfill a vision of cooperation, strengthening integration on issues pertinent to the region and to the future of the PLG. Its nine – American Samoa, French Polynesia, Niue, Cook Islands, Tokelau, Tuvalu, Tonga and Wallis Futuna, is argued to have strength in numbers, resources and diversity, and a positive addition to the growing regional diplomacies in the South Pacific.

Persuasive Communication

The message provides insights and tips on Persuasive Communication. It emphasizes the importance of being clear, concise, and confident in communication to influence others effectively. It also highlights the significance of understanding the audience and tailoring the message to their needs and preferences. Overall, the message aims to help individuals improve their persuasive communication skills for better outcomes in various interactions.

Diplomatic culture and its domestic context

Is there a specific, distinctive diplomatic culture? Given the fact that the conduct of diplomacy is regulated by international law and by custom, and since the structures through which states conduct their external relations, both bilateral and multilateral, are standardized, it is fair to say that both the institutions and the process form a pattern of their own, unique to this profession. The professional diplomatist actors on the international stage, and their institutions, display certain shared characteristics.

The Years of Talking Dangerously

In "The Years of Talking Dangerously," the author delves into the complexities of communication in modern times, exploring how words can impact relationships, society, and even global events. The book examines the power of language to shape perceptions and provoke change, emphasizing the importance of thoughtful dialogue in navigating the challenges of today's world.

Building relations through multi-dialogue formats: Trends in bilateral diplomacy

The text discusses the importance of building relationships through various dialogue formats in bilateral diplomacy.

Language, signaling and diplomacy

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): Ambassador Kishan Rana introduces the dimension of diplomatic signalling. Beginning with a reference to the Bhagwad Gita, one of the sacred texts of the Hindus, Rana outlines the qualities of good diplomatic dialogue: not causing distress to the listener, precision and good use of language, and truthfulness.

The Blair Years: Extracts from the Alastair Campbell diaries

Until his resignation amid huge controversy in August 2003, Alastair Campbell was Tony Blair’s official spokesman and director of communications and strategy – ace spin doctor, closest confidante, and constant travelling companion. His diaries have probably been mined chiefly for their astonishing revelations about the internal machinations of his government and the run-up to the invasion of Iraq in 2003. However, they should also be read for the sharp and often amusing light they throw on certain aspects of diplomacy.

Developments in protocol

As times change so do customs generally. In diplomacy protocol too changes and develops, mirroring broader societal norms. This paper discusses developments in protocol and how it provides the commonly accepted norms of behaviour for the conduct of relations between states.

Diplomacy and Developing Nations: Post-Cold War foreign policy-making structures and processes

The text discusses how post-Cold War foreign policy-making structures and processes impact diplomacy with developing nations.

Transformational Diplomacy after the Cold War: Britain’s Know How Fund in Post-Communist Europe, 1989-2003

This is the long awaited history of the Know How Fund (KHF) produced by the recently retired Foreign and Commonwealth Office historian Keith Hamilton. Like other FCO ‘internal histories’, it was initially written ‘to provide background information for members of the FCO, to point out possible lessons for the future and evaluate how well objectives were met.’

The role of the diplomatic corps: the US-North Korea talks in Beijing, 1988-94

In J. Melissen (ed.), Innovation in Diplomatic Practice, pp. 214-30 (Macmillan, London, 1999), ISBN 0-333-69122-9/

Foreign Ministries in the European Union

Foreign Ministries in the European Union collaborate on a range of global issues, focusing on effective diplomacy, promoting human rights, and fostering peace and security. Regular meetings and coordinated efforts help countries in the EU amplify their impact on the international stage. By working together, they aim to address challenges such as climate change, terrorism, and conflicts around the world. These foreign ministries play a crucial role in shaping EU policies and strategies while representing the collective interests of member states.

DC Confidential: The controversial memoirs of Britain’s ambassador to the U.S. at the time of 9/11 and the Iraq War

DC Confidential: The controversial memoirs of Britain's ambassador to the U.S. at the time of 9/11 and the Iraq War.

Digital diplomacy: Conversations on Innovations in Foreign Policy

The text discusses the role of digital diplomacy in shaping innovative foreign policy strategies.

Room For Diplomacy: Britain’s Diplomatic Buildings Overseas 1800-2000

Mark Bertram joined the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works after reading architecture at Cambridge and remained in the civil service as architect, project manager, administrator, estate manager and – in his own words – ‘quasi diplomat’ for the next thirty years. He was the ministry’s regional architect in Hong Kong in the 1970s, moved to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office when it secured control of its own buildings abroad (the ‘diplomatic estate’) in 1983, and was soon head of the estate department. On surrendering that role in 1997, he became a professional adviser to the ...

The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Diplomacy, Third Edition

Indispensable for students of diplomacy and junior members of diplomatic services, this dictionary not only covers diplomacy's jargon but also includes entries on legal terms, political events, international organizations, e-Diplomacy, and major figures who have occupied the diplomatic scene or have written about it over the last half millennium.

The Professional Diplomat