Authors: Petru Dumitriu European UnionInternational Labour OrganizationUnited NationsWorld BankWorld Trade Organization

Democratic Intergovernmental Organizations? Normative Pressures and Decision-Making Rules

2015

You may also be interested in

Switzerland’s good offices: a changing concept, 1945-2002

Switzerland's role in international diplomacy evolved from the end of World War II to 2002, showcasing its changing concept of good offices.

The Role of Regional Cooperation in Eradicating Poverty and Aid Dependency in East Africa

The hypothesis of this thesis is that regional cooperation and integration are effective tools in alleviating poverty within nations and reducing their dependency on foreign or development aid.

The European Union and the Latin American and the Caribbean Dialogue: Building a Strong Partnership

The text discusses the importance of building a strong partnership between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean through dialogue.

Peacemaking 1919

The message examines the peacemaking efforts of 1919, reflecting on the challenges faced during the time and lessons learned from the process.

The IberoAmerican System and its Influence in the Ibero-American Regional Summit Diplomacy

The IberoAmerican System plays a crucial role in the Ibero-American Regional Summit Diplomacy, fostering collaboration and partnership between participating countries in the region.

From U Thant to Kofi Annan: UN Peacemaking in Cyprus, 1964-2004

2004 marked the fortieth anniversary of the United Nations presence in Cyprus. Since March 1964, the UN has been responsible for addressing and managing both peacekeeping and peacemaking efforts on the island.

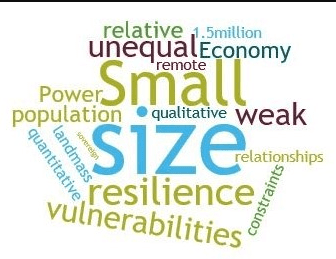

What are the priorities for small states in the international system?

There is no evidence that the vigorous political action needed to implement the recommendations of previous reports on the vulnerability of small states in the Commonwealth will be forthcoming in the near future. In matters of security, economics and particularly the environment, the collective interests of small states do not appear to have been recognized in the international community. Major donors find dealing with small individual demands from multiple small states difficult, but a regional approach simplifies matters and should be the primary area of concern. The Vulnerability Index prov...

Diplomacy Before and After Conflict

The importance of diplomacy in preventing conflicts is highlighted in this text. Diplomatic efforts both before and after conflicts are crucial for resolving disputes peacefully. Diplomacy plays a key role in preventing escalation of tensions, promoting understanding, and finding mutually acceptable solutions. It emphasizes the need for respectful communication, negotiation, and compromise to maintain peace and stability in the international arena. Diplomatic channels must be utilized effectively to address grievances, build trust, and foster cooperation among nations. Diplomacy is a vital too...

Leadership Selection in the Major Multilaterals

Inspired by the damaging leadership contest fiascos of recent years in certain international organizations, not least that in the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1998-9, this is a timely and important book. Kahler emphasises that if these bodies do not abandon their old, creaking 'club system of governance' and get their acts together, they will lose their already precarious support in the US Congress and forfeit that of their increasingly assertive members among the developing countries, particularly the large emerging market-economies. With the institutions of global governance thus put at...

Humanitarian intervention and international society

The text discusses the concept of humanitarian intervention within international society.

The MIKTA Way Forward (Briefing Paper #2)

Ms Rosen Jacobson assesses the potential, risk, and future of MIKTA, a cooperation scheme comprising Mexico, Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, Turkey, and Australia, which was officially launched in September 2013.

The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the Accra Agenda for Action

The Paris Declaration and Accra Agenda highlight key principles and actions for improving aid effectiveness in developing countries, emphasizing ownership, alignment, harmonization, managing for results, and mutual accountability among donors and recipients. They aim to enhance the impact of aid by promoting transparency, participation, and partnership in the development process.

UN Conferences: Media events or genuine diplomacy?

The text scrutinizes the nature of UN conferences, questioning whether they serve primarily as media spectacles or genuinely effective diplomatic forums for addressing global challenges.

Unvanquished: A U.S.-U.N. Saga

Question: When is a diplomatic victory not a diplomatic victory? Answer: When it is achieved by means of a veto in the Security Council of the United Nations. Nowhere is this maxim more tellingly illustrated than in the Council's meeting in New York in November 1996 which voted on the issue of whether or not to give a full second term (five years) to the Secretary-General, the University of Paris educated Egyptian scholar-diplomat, Dr Boutros Boutros-Ghali. Of the 15 members of the Council, 14 voted in favour and one voted against. Since that member was the United States this represented a vet...

Mainstreaming Development in the WTO

The text discusses the importance of incorporating development goals into the World Trade Organization's (WTO) agenda to ensure more inclusive and sustainable global trade policies. It emphasizes the need for a balance between trade liberalization and development objectives to address the challenges faced by developing countries in the global trading system. It calls for mainstreaming development in the WTO's decision-making processes to promote fair and equitable trade practices that benefit all member countries.

Enhancing Global Governance: Towards a New Diplomacy

The text is about the importance of improving global governance through a new approach to diplomacy.

Activities of the Department of Public Information: Strategic communications services

The Department of Public Information provides strategic communications services.

UN conferences on the spot – voices from civil society

In the fourth chapter of the book, Britta Sadou, focuses on non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Sadou introduces this particular group as civil society actors and continues by discussing possibilities provided to NGOs by various UN summits. The author highlights some of the main world conferences during the 1990s and early 2000s and poses two important questions - Has the time of those huge events come to an end? What could be the alternatives?

United Nations-Sponsored World Conferences: Focus on Impact and Follow-up

United Nations-sponsored world conferences aim to focus on the impact and follow-up actions of global initiatives.

Negotiating and Navigating Global Health: Case Studies in Global Health Diplomacy

The text presents case studies illustrating the complexities and strategies involved in negotiating and navigating global health issues, shedding light on the dynamic intersection of health diplomacy and international relations.

Reforming the United Nations: The Challenge of Working Together

Reforming the United Nations: The Challenge of Working Together" discusses the complexities of reforming the United Nations to enhance its effectiveness. It emphasizes the importance of collaboration and cooperation among member states to address global challenges and make the organization more responsive to current needs. The article highlights the need for transparency, accountability, and flexibility in the reform process to ensure the United Nations remains a relevant and impactful international institution.

21st century health diplomacy: A new relationship between foreign policy and health

The 21st century sees a shift towards the integration of foreign policy and health, emphasizing the importance of health diplomacy in global affairs.

Searching for Meaningful Human Control. The April 2018 Meeting on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (Briefing Paper #10)

In this briefing paper, Ms Barbara Rosen Jacobson analyses the debate of the April 2018 meeting of the Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW). The group was established to discuss emerging technologies in the area of lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS).

The Clash of Globalizations: Essays on the Political Economy of Trade and Development Policy

The Clash of Globalizations: Essays on the Political Economy of Trade and Development Policy explores the tensions between different approaches to globalization, examining how they impact trade and development policy.

The Kyoto Protocol: International Climate Policy for the 21st Century

The Kyoto Protocol is considered a fundamental agreement in international climate policy for the 21st century, aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to combat global warming.

Global Health Diplomacy: Concepts, Issues, Actors, Instruments, Fora and Cases

The message provides information on global health diplomacy, covering concepts, issues, actors, instruments, fora, and cases.

Engineering Influence: The Subtile Power of Small States in the CSCE/OSCE

The text discusses the significant impact small states have within the CSCE/OSCE through their diplomatic strategies and ability to shape agendas and outcomes.

Securing the Future of Multilateral Development Finance: Time for Europe to take the Initiative

The message emphasizes the importance of Europe taking the lead in securing the future of multilateral development finance.

European Union external action structure: Beyond state and intergovernmental organisations diplomacy

This dissertation analyses the organisation of the external action structures of the European Union. As an international actor which is beyond a state, but also different to traditional international organisations, the EU has created a “diplomatic constellation” in which diplomacy from member states is not substituted but complemented by EU external action.

The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy

The message provides information on modern diplomacy from The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy.

Diplomacy as an instrument of good governance

The functioning of diplomacy is influenced by a complicated combination of different interrelated factors. This paper briefly analyses their impact on the evolution of diplomacy and discusses how diplomacy as an instrument of good governance should adjust itself to meet the new challenges, to become more relevant, open and agile, to modify its methods and to fully utilise opportunities offered by the technological revolution.

Triangular Co-operation and Aid Effectiveness: Can triangular co-operation make aid more effective?

The text discusses the potential for triangular cooperation to enhance the effectiveness of aid.

Democratic Intergovernmental Organizations? Normative Pressures and Decision-Making Rules

At first sight, the very choice of the title of this book may indicate that the author, Alexandru Grigorescu, was not sure about the existence of such thing. Indeed, to be or not to be democratic is not a top concern on the internal agenda of international organizations. Therefore, Grigorescu’s fresh endeavour to find an answer to such a purposeful question is ab initio a praiseworthy academic démarche.

Small states and NATO: Influence and accommodation

The influence and accommodation of small states within NATO is a vital aspect of the alliance's dynamics. These states play a significant role in shaping NATO's decisions and policies, despite their size. It is essential for NATO to consider the perspectives and needs of small states to ensure their full engagement and commitment to the alliance's collective security goals. Balancing the interests of both small and large states is crucial for NATO's effectiveness and cohesion.

Use of language in diplomacy

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): Ambassador Stanko Nick takes a practical approach, examining issues such as the choice of language in bilateral and multilateral meetings, the messages conveyed by language choice, difficulties posed by interpretation, and aspects of diplomatic language including nuance, extra-linguistic signalling, and understatement. Language, according to Nick, is not a simple tool but "often the very essence of the diplomatic vocation."

Return to the UN: United Nations diplomacy in regional conflicts

‘… lively … persuasive … careful analysis… This is a very readable study, combining narrative strength with political acuity, and informative on the years of disappointment … Much has changed since the UN’s annus mirabilis, but Berridge’s conclusions still stand’, Nicholas Sims, London School of Economics, Millenium.

Herding Cats: Multiparty Mediation in a Complex World

Review by Geoff Berridge

Decision-Making in the UN Security Council: The case of Haiti, 1990-1997

Question: 'When is a "Foreword" not a "Foreword"? Answer: When it is written by Adam Roberts. This book started life as an Oxford doctoral thesis under the supervision of Professor Roberts, and the former supervisor has done both the former student and readers of this book a great service by prefacing it with a seven-page essay in which he underlines its importance in convincing detail. So this, unlike ninety-nine per cent of examples of the same genre, is a Foreword that should not be ignored.

Innovation in Diplomatic Practice

The text discusses the need for innovation in diplomatic practice to address modern challenges effectively. Diplomats must adapt to changing dynamics, such as digital diplomacy and non-state actors, to achieve diplomatic objectives successfully. Traditional diplomatic methods may need to be revised or replaced to meet the demands of contemporary international relations. Innovation and creativity are essential for diplomats to navigate complex global issues and promote peace and cooperation among nations.

Hanging Together: Cooperation and conflict in the seven power summits

The text discusses the dynamics of cooperation and conflict within seven power summits.

The World Bank’s Contribution to Poverty Reduction in Peru

Peru’s economy has improved significantly, however poverty is an imperative issue that is not progressing as expected.

Multilateral Conferences: Purposeful International Negotiation

Ron Walker was a member of the Australian diplomatic service for 37 years, for the last 22 of which (1975-96) he specialized in multilateral diplomacy. His book on this subject is not an academic book. Instead he has done for multilateral diplomacy what Kishan Rana has done for bilateral diplomacy, namely, provided on the basis of long and wide experience, much at a senior level, a splendid handbook of practical advice for the novice.

Security Council reform: Why it matters and why it’s not happening

This message discusses the importance of Security Council reform and the challenges hindering its progress.

The United Nations and Israel

This dissertation studies the relationship between the United Nations and Israel. Similar to most relationships, the one under review keeps evolving due to changing internal realities and emerging external factors.

Power: The nexus of global health diplomacy?

The text appears to be missing content within the triple quotes. Could you please provide the content so that I can summarize it for you?

Reforming the Working Methods of the UN Security Council: The Next ACT

ACT is a new group of 22 UN member states that is pressing for reform of the working methods of the UN Security Council in order to improve its accountability, coherence and transparency. To achieve its aims, ACT will have to avoid being caught up in the stalled debate over Council membership reform. The group, currently dominated by small states, will also need new partners from different geographical regions, and with more political weight. Moreover, if ACT wants to involve the permanent members of the Security Council, it may have to limit its emphasis on the role of the veto. ACT aim...

Declaration of the Global African Diaspora Summit

The text describes the Global African Diaspora Summit as a significant platform for discussing issues affecting people of African descent worldwide, fostering unity, and promoting economic development and social inclusion within the diaspora.

Framework of operational guidelines on United Nations support to South-South and triangular cooperation

The message provides a framework of operational guidelines for United Nations support to South-South and triangular cooperation.

Multistakeholder Diplomacy – Challenges and Opportunities

This book is a collection of papers from Diplo’s February 2005 conference in Malta and from research interns involved in our Multistakeholder Diplomacy internship programme.

International Diplomacy Volume III: The Pluralisation of Diplomacy

The message is not present.

The United Nations: An Introduction

The United Nations is an international organization aiming to promote peace, cooperation, and sustainable development among nations through diplomacy, dialogue, and collaboration. Its key bodies include the General Assembly, Security Council, and specialized agencies like the World Health Organization and UNICEF. By providing a platform for member states to address global challenges together, the UN plays a vital role in fostering international relations and addressing issues such as human rights, climate change, and armed conflicts.

WHO reform process: documents

The World Health Organization (WHO) reform process involves various documents that outline proposed changes and improvements to the organization.

The WTO Agreements: Deficiencies, Imbalances and Required Changes

The text discusses the deficiencies, imbalances, and necessary changes needed within the WTO Agreements.

Multilateral Diplomacy and the United Nations Today

As the world confronts new and ongoing challenges of globalization, international terrorism and an array of other global issues, the United Nations and its key attribute-multilateral diplomacy-are more important now than ever before. With new and updated essays that detail the experiences of a diverse group of practitioners and scholars who work in the field of diplomacy, this new edition covers in even greater breadth and depth the quintessential characteristics of multilateral diplomacy as it is conducted within the United Nations framework. Multilateral Diplomacy and the United Nations Toda...

The United Nations and Development: From Aid to Cooperation

The text examines the evolution of the United Nations' approach to development, emphasizing the transition from traditional aid-based strategies to collaborative cooperation frameworks aimed at sustainable development outcomes.

Envisioning Reform: Enhancing UN Accountability in the Twenty-first Century

The text discusses the need to enhance UN accountability in the twenty-first century through reform.

The Oxford Handbook on the United Nations

The Oxford Handbook on the United Nations offers a comprehensive examination of the organization, detailing its history, structure, functions, and impact on global affairs. Covering topics such as peace and security, human rights, development, and international law, this handbook provides valuable insights into the UN's role in addressing global challenges and promoting cooperation among member states. Scholars, policymakers, and students will find this resource to be a valuable reference for understanding the complexities of the United Nations and its significance in the international landsca...

The Organization of Global Negotiations: Constructing the Climate Change Regime

The text discusses the importance of organizing global negotiations to construct the Climate Change Regime effectively.

A New Wave for the Reform of the Security Council of the United Nations: Great Expectations but Little Results

The reform of the Security Council of the United Nations (UNSC) has been an elusive issue at the United Nations (UN). While practically all Member States agree on the need to change the structure of the most powerful body of the world organization, so far there has been no agreement about what elements of that reform or about the substance of the reform itself.

ASEAN Education Ministers Meeting (ASED)

Summary: The message will provide information related to the upcoming ASEAN Education Ministers Meeting (ASED).

International Diplomacy Volume IV: Public Diplomacy

The text explores the domain of public diplomacy within the broader context of international diplomacy, offering insights into the evolving strategies and practices of statecraft aimed at engaging and influencing foreign publics.

Negotiating Public Health in a Globalized World: Global Health Diplomacy in Action

The text is about the challenges and opportunities of negotiating in the global health diplomacy landscape, emphasizing the importance of collaboration and innovation to address public health issues on a global scale.

Global Health and Foreign Policy

Global health and foreign policy are closely intertwined as health issues have significant impacts on international relations and diplomacy. Collaborative efforts between countries are essential to address global health challenges and promote well-being worldwide.

International Diplomacy Volume II: Diplomacy in a Multicultural World

The text discusses the importance of multiculturalism in diplomacy to achieve mutual understanding and cooperation among nations, emphasizing the significance of cultural sensitivity and respect in international relations.

The future of (multilateral) diplomacy? Changes in response to COVID-19 and beyond

The year 2020 marked the 75th anniversary of the United Nations (UN). It is also the year that the world was faced with responding to the emergence of the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, an unprecedented global challenge that has left no area of society and no individual life untouched.

Funeral summits

Berridge, G. R. (1996) 'Funeral summits', in David H. Dunn (ed.), Diplomacy at the Highest Level: The evolution of international summitry (Macmillan - now Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke).

Security for small states

The text discusses the importance of small states being proactive in ensuring their security by engaging in partnerships, investing in defense capabilities, and utilizing diplomatic strategies. It emphasizes the need for small states to take ownership of their security and collaborate with allies to navigate global challenges effectively.

Preference-Dependent Economies and Multilateral Liberalization: Impacts and Options

The text examines the impacts and options surrounding multilateral liberalization within preference-dependent economies, shedding light on the complexities and considerations involved in navigating trade policies in such contexts.

The Roads from Rio: Lessons Learned from Twenty Years of Multilateral Environmental Negotiations

The text discusses key lessons learned from two decades of multilateral environmental negotiations, emphasizing insights gained since the Rio conference.

The International Climate Change regime: A Guide to Rules, Institutions and Procedures

The International Climate Change regime is a comprehensive guide that outlines the rules, institutions, and procedures related to addressing climate change on a global scale.

Small developing economies and the multilateral trading system: A Caribbean perspective

Small developing economies are often constrained in participating in the negotiation and regulation of multilateral trading rules due to severe cost and resource limitations. This article argues that, despite the costs and difficulties, small states must remain engaged in the multilateral trading system in order to ensure that their specialised commercial interests are recognised and to protect their rights. Umbrella entities like the Caribbean Regional Negotiating Machinery (CRNM) provide a means of maximising the influence of small states in an international forum such as the World Tra...

Diplomacy on a south-south dimension

Building international diplomacy requires understanding ourselves, others, and how we relate together. It also involves understanding how others relate among themselves. In efforts to internationalise and build a truly global future, the consideration of contacts among all parts of the world becomes critical. The sustained diplomatic cooperation that has taken place in the last 50 years between China and African nations is an instructive example. This major phenomenon is the focus of this paper.

Regional and Multilateral Trade Agreements: Complementary Means to Open Markets

The article discusses the benefits of both regional and multilateral trade agreements in opening markets effectively.

Towards a secure cyberspace via regional co-operation

The study Towards a secure cyberspace via regional co-operation provides an overview of the international dialogue on establishing norms of state behaviour and confidence-building measures in cyberspace.

Backstabbing for Beginners: My Crash Course in International Diplomacy

On 21 April 2004, the Security Council adopted resolution 1538(2004), the most embarrassing resolution in the history of the United Nations. The resolution appointed an independent high-level inquiry whose mandate was to 'collect and examine information relating to the administration and management of the Oil-for-Food Programme, including allegations of fraud and corruption on the part of United Nations officials, personnel and agents, as well as contractors, including entities that have entered into contracts with the United Nations or with Iraq under the Programme.'

ADF-13 Report: Supporting Africa’s Transformation

The message summarizes the content of the ADF-13 report, which focuses on supporting Africa's transformation.

What is Global Health Diplomacy? A Conceptual Review

The article explores the concept of global health diplomacy, highlighting its complexity and interdisciplinarity. It emphasizes the importance of collaboration between various sectors, such as health and foreign affairs, to address global health challenges effectively. Key components include negotiation, advocacy, and communication skills, alongside political awareness and cultural sensitivity. The review underscores the need for innovative strategies to tackle health issues on a global scale through diplomatic efforts that prioritize equity, solidarity, and cooperation among nations.

The globalization of public health: the first 100 years of international health diplomacy

Global threats to public health in the 19th century sparked the development of international health diplomacy. Many international regimes on public health issues were created between the mid-19th and mid20th centuries. The present article analyses the global risks in this field and the international legal responses to them between 1851 and 1951, and explores the lessons from the first century of international health diplomacy of relevance to contemporary efforts to deal with the globalization of public health.

Ten theoretical clues to understanding United Nations reform (Briefing Paper #6)

The message provides ten theoretical clues for understanding United Nations reform in Briefing Paper #6.

Managing Global Chaos

The message deals with strategies for managing global chaos. It discusses the importance of adaptability, resilience, and communication in navigating turbulent international waters. Leaders are advised to anticipate challenges, foster collaboration, and maintain a proactive approach to addressing crises on a global scale. The text emphasizes the need for flexibility and innovation to effectively manage chaos in a rapidly changing world.

The road to dignity by 2030: ending poverty, transforming all lives and protecting the planet

The message emphasizes the goal of achieving dignity by 2030 through ending poverty, transforming lives, and preserving the environment.

The Peace Brokers: Mediators in the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1948-79

The text discusses the role of mediators in the Arab-Israeli conflict from 1948 to 1979.

The impact of cultural diversity on multilateral diplomacy and relations

Basic concepts mean different things in different cultures. In multilateral relations this means that looking at such a concept is always culturally biased. As a result, an interpretation according to one culture also tends to criticise different interpretations according to other cultures. This paper discusses how important it is that diplomats and politicians pay attention to and accept the fact of cultural diversity. If they do, they will understand the underlying causes of many conflicting attitudes and they may become more inclined to seek compromise and consensual approaches rather than ...

The UN and the world diplomatic system: lessons from the Cyprus and US- North Korea talks

In Bourantonis, D. and M. Evriviades (eds), A United Nations for the Twenty-First Century(Kluwer Law International, 1996), pp. 105-16

International Diplomacy Volume I: Diplomatic Institutions

The message provides information related to international diplomacy found in "International Diplomacy Volume I: Diplomatic Institutions.

On Behalf of My Delegation,…: A Survival Guide for Developing Country Climate Negotiators

The one hundred pages of this book are in fact a useful Survival Guide for those approaching climate change negotiations for the first time. It has been written for developing country delegates, but delegates from other countries can also profit from its reading the same way that a similar survival guide for industrialized country delegates would be useful for those coming from developing countries, because it is necessary to know both sides of the story

Ambiguity versus precision: The changing role of terminology in conference diplomacy

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): Of central concern in the field of negotiation is the use of ambiguity to find formulations acceptable to all parties. Professor Norman Scott looks at the contrasting roles of ambiguity and precision in conference diplomacy. He explains that while documents drafters usually try to avoid ambiguity, weaker parties to an agreement may have an interest in inserting ambiguous provisions, while those with a stronger position or more to gain will push for precision.

Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

The Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change outlines international commitments to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to combat climate change.

Global Health, Aid Effectiveness and the Changing Role of the WHO

The text discusses the changing role of the World Health Organization (WHO) in the context of global health and aid effectiveness.

Multilateral Institutions: Building New Alliances, Solving Global Problems

The mountain of global problems, viz. the list of world tasks that can be solved only collectively by the international community, continues to grow. At the same time, the multilateral institutions find themselves in the midst of a difficult process of change, one marked by a high degree of mistrust and fragmentation in the international community as well as by a low level of willingness and ability to tackle global tasks in the multilateral framework. This trend has been due to certain unilateral reflexes that emerged when the Cold War drew to a close and above all to the experiences th...

Facing the challenges of an Africa-wide ICT strategy

'There is a need to address these challenges to enhance the capacity of the AU organs, institutions and member states to better respond to instances of ICT policy in Africa. As part of the evolving African governance architecture, there is a need to formulate an ICT strategy...' - Eliot Nsega from Uganda

What’s the World Health Organization For?

The text discusses the purpose and functions of the World Health Organization (WHO), highlighting its role in global health and disease prevention.

Assessing implementation mechanisms for an international agreement on research and development for health products

The Member States of the World Health Organization (WHO) are currently debating the substance and form of an international agreement to improve the financing and coordination of research and development (R&D) for health products that meet the needs of developing countries. In addition to considering the content of any possible legal or political agreement, Member States may find it helpful to reflect on the full range of implementation mechanisms available to bring any agreement into effect. These include mechanisms for states to make commitments, administer activities, manage financial co...

Common African Position on the Post-2015 Development Agenda

The participatory approach that led to the elaboration of the Common African Position (CAP) on the post-2015 Development Agenda involving stakeholders at the national, regional and continental levels among the public and private sectors, parliamentarians, civil society organizations (CSOs), including women and youth associations, and academia. This approach has helped address the consultation gap in the initial preparation and formulation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Diplomacy at the Highest Level: The Evolution of International Summitry

The text discusses the evolution of international summitry and how it has become a key tool for diplomacy at the highest levels.

Mediation in the Yugoslav Wars: The Critical Years, 1990-95

The book "Mediation in the Yugoslav Wars: The Critical Years, 1990-95" explores the role of mediation in the Yugoslav Wars during the crucial period from 1990 to 1995. It delves into the efforts made by various individuals and organizations to mediate the conflicts that arose during this time. Through a detailed examination of mediation attempts, the book sheds light on the complexities and challenges faced in trying to bring about peace in the region.

The Reform of the United Nations

The text discusses the Reform of the United Nations.

The Role of Small States in the Multilateral Framework

The current world geopolitical configuration shows how after the end of a bipolar world set by the top superpowers (United States and the Ex Soviet Republic) along with other major players (such as Germany, Great Britain, France, Japan and China, the P5 United Nations Security Council members + 1 with the full capacity of veto power in all world top decisions and procedures) set up a new world reconfiguration that has emerged since the end of the twenty century and mainly in the beginning of this 21th century standing driven from some centers of power and in parasailed with the political and e...

Summitry in the Americas: The End of Mass Multilateralism?

Summits among large numbers of leaders that convene on a periodic basis are the “new diplomacy.” In the Western Hemisphere, summits continue to multiply, whether in response to specific issues or to the desire by certain countries to assert their leadership. At the same time, skepticism regarding the value of summits has become widespread. A common view is that summits are largely photo ops for leaders and that their lofty communiqués are soon forgotten, leaving a wide gap between aspirations and implementation. These frustrations notwithstanding, summits are here to stay. Gathering...

The evolution of diplomacy in the Caribbean

This paper will focus on the development of diplomacy in the Caribbean and how it impacts the development of small Caribbean States, paying attention to the regional, bilateral and multilateral levels of diplomacy.

The study of regional integration

The study of regional integration involves examining the process of countries coming together to form agreements, policies, and institutions to promote cooperation and economic growth within a specific geographic area. This can involve various levels of integration, such as free trade agreements, customs unions, and common markets, with the ultimate goal of fostering closer relationships between nations to achieve mutual benefits and common goals.

Changing with the World: UNDP Strategic Plan 2014-17

With the changing world as the backdrop, and building on our core strengths, our vision is focused on making the next big breakthrough in development: to help countries achieve the simultaneous eradication of poverty and significant reduction of inequalities and exclusion. This is a vision within reach, with the eradication of extreme poverty and major reductions in overall poverty feasible within a generation. It should be possible as well to make significant inroads against income and non- income measures of inequality and exclusion within this time frame.

Multilateral Aid 2015: Better Partnerships for a Post-2015 World

The message emphasizes the importance of improving partnerships in multilateral aid for a post-2015 world.

The development of multilateral diplomacy and its fundamental role in global security and progression.

This dissertation is written to present the notion of peace and security to be the direct result of international cooperation through multilateral means

Global health diplomacy: How foreign policy can influence health

Ilona Kickbusch argues that public health experts need to work with diplomats in order to achieve global health goals.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change aims to address global warming by promoting international cooperation and agreements to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change impacts.

Our Global Neighbourhood

The text discusses the importance of global cooperation and the need for collaborative efforts to address various global challenges and create a sustainable and peaceful world. It emphasizes the interconnectedness of nations and the shared responsibility to work together for the betterment of all.

Multilateralism under Challenge? Power, International Order, and Structural Change

The values and institutions of multilateralism are not ahistorical phenomena. They are created and maintained in the context of specific demands and challenges, and through specific forms of leadership, norms, and international power configurations. All of these factors evolve and change; there is little reason to believe that multilateral values or institutions could or should remain static in form and nature. The relationship between the distribution of power, the nature of challenges and problems, and the international institutions that emerge to deal with collective challenges is const...

Alliances and Small Powers

This message was empty and did not contain any content to summarize.

The Role of Diplomacy in the Challenges to Maritime Security Cooperation in the Gulf of Guinea: Case Study of Nigeria

There is presently a pervading feeling that the West and Central African states are long overdue to take control of their maritime environment. However, these expectations show no indication of materialising in the short term.

The Procedure of the UN Security Council

The UN Security Council is a key body within the United Nations composed of 15 members, 5 permanent and 10 elected, responsible for maintaining international peace and security. It addresses threats to peace, enacts sanctions, and authorizes military action when necessary, with decisions requiring at least 9 affirmative votes. The Council operates through meetings, where issues are discussed and decisions are made. Additionally, it has subsidiary bodies and committees to address specific matters. The members hold significant responsibility in addressing global challenges and conflicts effectiv...

Trends and Progress in International Cooperation: Report of the Secretary-General

The report discusses the current state and trends in international cooperation.

Digital Diplomacy as a foreign policy statecraft to achieving regional cooperation and integration in the Polynesian Leaders Group

Established in 2011, the Polynesian Leaders Groups serves to fulfill a vision of cooperation, strengthening integration on issues pertinent to the region and to the future of the PLG. Its nine – American Samoa, French Polynesia, Niue, Cook Islands, Tokelau, Tuvalu, Tonga and Wallis Futuna, is argued to have strength in numbers, resources and diversity, and a positive addition to the growing regional diplomacies in the South Pacific.

The Hypocrisy Threatening the Future of the Internet

The message highlights the threat of hypocrisy to the future of the internet, raising concerns about the negative impact of inconsistent actions and standards on the digital landscape.

The Grand Decade for Global Health: 1998-2008

Jon Lidén's text examines the significant developments and achievements in global health during the pivotal period from 1998 to 2008, highlighting key initiatives and challenges that shaped the landscape of public health on a global scale.

Manual on Compliance with and Enforcement of Multilateral Environmental Agreements

The text provides comprehensive guidance on compliance with and enforcement of multilateral environmental agreements, offering practical strategies and tools for enhancing global environmental governance.

Climate for Change: Non-state Actors and the Global Politics of the Greenhouse

The text explores the role of non-state actors in global climate politics, analyzing their impact on greenhouse gas emissions and environmental policies. These actors include businesses, NGOs, and local governments, who often operate independently of national governments to address climate change. Their efforts are crucial in mitigating the effects of global warming and pushing for stronger environmental regulations on a global scale.

Consensus Rule Processes

The text highlights the benefits and challenges of consensus processes, emphasizing that while they ensure decisions meet all parties' interests and garner support, they can be slow, have a high probability of failure, and may not work for quick decisions, favoring those who oppose change and can delay progress by refusing compromise, necessitating control of escalation and skilled facilitation for successful outcomes.

Summitry as intercultural communication

In one of his last essays before his premature death in 1972, Martin Wight described international conferences as ‘the set pieces punctuating the history of the European states-system, moments of maximum communication’.

Old diplomacy in New York

The message details the use of old diplomacy in New York, focusing on traditional methods being employed to navigate modern challenges.

A Tipping Point for the Internet: Predictions for 2018 (Briefing Paper #9)

The briefing paper discusses various predictions for the internet in 2018, focusing on key trends and developments that will shape the digital landscape. Key areas include the rising importance of cybersecurity, the impact of artificial intelligence on online platforms, growing concerns over data privacy, increased regulation of tech giants, and the potential for blockchain technology to revolutionize various industries. These trends are expected to drive significant changes in how we use and interact with the internet in the coming year.

Reforming the World Trade Organisation: Developing Countries in the Doha Round

In tne text, the focus is on the necessity of reforming the World Trade Organisation to better support developing countries participating in the Doha Round negotiations. Key points likely include addressing imbalances in trade rules, improving access to markets, and ensuring fair treatment for developing nations in the global trade arena.

Tunis Agenda for the Information Society

The Tunis Agenda for the Information Society highlights the need to bridge the digital divide, prioritize the development of ICT infrastructure in developing countries, promote internet governance principles, and ensure a people-centered, inclusive, and development-oriented information society. It emphasizes the importance of multilateralism, capacity building, and creating an enabling environment for sustainable ICT development. The document serves as a roadmap for advancing the global information society and ha...

Multilateral Conferences and Diplomacy: A Glossary of Terms for UN Delegates

The text will provide a glossary of terms related to multilateral conferences and diplomacy for UN delegates.

Multilateral Diplomacy: The United Nations System at Geneva: A Working Guide

The message provides guidance on the United Nations System at Geneva, focusing on multilateral diplomacy.

The Role of the United Nations in Making Progress Towards Peace in Burundi

The United Nations plays a crucial role in facilitating peace efforts in Burundi through conflict resolution, peacekeeping, and promoting dialogue among various stakeholders in the region.

Reform of the United Nations Security Council

The text discusses the need for reform of the United Nations Security Council to make it more representative and effective in addressing global security challenges.

Strengthening the region’s participation

‘Witnessing the open community policy development process at the AfriNIC community led me to further appreciate the importance of the Policy Research Phase of the Diplo IGCBP. AfriNIC-13 was an eye opener...’ - Maduka Attamah from Nigeria

Caribbean Diplomacy: Research on Diplomacy of Small States

With little recourse to traditional economic and political power in their international relations, diplomacy for Caribbean states is a key mechanism to achieve the realisation of the region’s overall development agenda. The Caribbean is no stranger to diplomatic challenges.

The New Economic Diplomacy

The New Economic Diplomacy focuses on how the intersection of economics and foreign policy is shaping international relations in the modern world. It discusses how economic tools are increasingly being used to achieve political objectives and how countries are utilizing economic diplomacy to advance their interests on the global stage. This shift towards a more economically driven approach to diplomacy reflects the changing dynamics of international relations and highlights the growing importance of economic considerations in foreign policy decision-making.

Summits: Six Meetings that Shaped the Twentieth Century

Summits: Six Meetings that Shaped the Twentieth Century" explores the impact of six key summits in the 20th century, highlighting their significance in shaping global politics and history. These meetings, involving world leaders like Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, and Kennedy, influenced major events such as the Cold War, arms control negotiations, and diplomatic relations. Through detailed analysis, the book demonstrates how these summits played a crucial role in shaping the geopolitical landscape of the 20th century.

Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems: Mapping the GGE Debate (Briefing Paper #8)

The paper discusses the ongoing debate in the Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS) and the varying perspectives on the need for regulation and control of these weapons.

Unvanquished: A U.S.-U.N. Saga

In November 1996, the U.S. wielded its veto power in the U.N. Security Council to prevent Boutros Boutros-Ghali from securing a second term as Secretary-General, despite overwhelming support. The U.S. had attempted various tactics, including disinformation and pressure on other council members, to oust him. Boutros-Ghali's memoir sheds light on the U.S.'s dismissal of diplomacy in this instance, emphasizing the power dynamics at play. The event underscored the potential weakening of the U.N. diplomatic system.

How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance

The book "How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance" presents a blueprint for solving global problems by leveraging networks of individuals and organizations. It explores the potential for a new era of collaboration and innovation to address pressing issues on a global scale, highlighting the power of interconnectedness and collective action in shaping a better future for all.

Culture and Organizations: Software of the Mind

This text explores the role of culture in shaping organizations and individuals' behaviors and beliefs. It explains how culture influences the way people act and interact within a specific group or society, serving as a mental software that guides thoughts and actions. Understanding cultural differences is crucial for effective communication and collaboration in diverse settings.

Multilateral Negotiations: From Strategic Considerations to Tactical Recommendations

The text provides strategic insights and tactical recommendations for navigating multilateral negotiations effectively, offering guidance on achieving diplomatic goals in complex international settings.

Multilateral Diplomacy for Small States: The Art of Letting Others Have Your Way

Multilateral Diplomacy for Small States: The Art of Letting Others Have Your Way

Surrender is Not an Option: Defending America at the United Nations and Abroad

In the book "Surrender is Not an Option: Defending America at the United Nations and Abroad," the author emphasizes the importance of standing firm in defense of America's interests, explaining that surrender should never be considered as a viable option in international relations. The book likely offers insights into strategies for navigating diplomatic challenges while maintaining a strong stance on key issues.

Work Programme on Electronic Commerce

The text outlines the World Trade Organization's work program on electronic commerce, focusing on discussions and negotiations aimed at establishing rules and frameworks to govern digital trade in the global economy.

United Nations Handbook 2015-16

The United Nations Handbook 2015-16 provides comprehensive information on the organization's structure, goals, and activities. It serves as a valuable resource for understanding the UN's role in promoting peace, security, and development globally. The handbook covers various topics such as peacekeeping, human rights, and sustainable development, offering insights into the UN's efforts to address pressing global challenges. This resource is essential for policymakers, diplomats, students, and anyone interested in international relations.

Prenegotiation and Mediation: The Anglo-Argentine Diplomacy after the Falklands/Malvinas War (1983-1989)

This paper studies the process of prenegotiation and the role of mediators during the negotiations between the Argentine and British governments about the dispute over the sovereignty of the Falkland/Malvinas Islands from immediately after the war of 1982 to 1990. In this period, the relationship between both governments evolved from rupture and no-relations to the agreement on the conditions to negotiate the renewal of full diplomatic relations concluded in early 1990. In a preliminary process of prenegotiation, the governments of Switzerland, initially, and the United States played a ro...

Modernising Dutch Diplomacy

The Dutch government is making investments in the modernization of its diplomatic services to enhance its efficiency, effectiveness, and digital capabilities. This upgrade aims to position the Netherlands as a leader in global diplomacy by adapting to the changing international landscape and embracing innovation.

Small States in International Relations

The text discusses how small states navigate the complexities of international relations, highlighting their unique challenges and strategies for exerting influence on the global stage.

Strengthening Regional Management: A Review of the Architecture for Regional Co-operation in the Pacific

The review focuses on the architecture for regional co-operation in the Pacific and aims to strengthen regional management in the area.

International Organisation in World Politics

The text highlights the increasing importance of international organizations since the end of the Cold War, particularly the United Nations and the European Union, in addressing major security issues and global challenges, while also emphasizing the emergence of a structure of global governance and the role of international non-governmental organizations and social movements in shaping global civil society.

Knowledge management: experience from international organisations

In this chapter, John Pace decribes the three-phase evolution of knowledge management in the human rights program of the United Nations. The realisation that knowledge management is a necessity came during the third phase. The author also describes the complex system of monitoring bodies and ad hoc mechanisms, and the developments that took place following four decisions taken in the mid-eighties.

A United Nations for the Twenty-First Century

The United Nations needs to be reformed to effectively address global challenges in the modern era. More representation, increased funding, and a focus on prevention rather than reaction are crucial for the organization to be successful in the twenty-first century.

Internet Governance: A Grand Collaboration

This publication is an edited collection of papers contributed to the United Nations ICT Task Force Global Forum on Internet Governance (New York, 25 - 26 March 2004). The papers provide useful information on how many different organizations are already governing the Internet and its effects on society.

Modern Diplomacy – Opening address

Opening address of the Honourable Dr. George F. Vella, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Environment of Malta.

Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is a comprehensive plan that outlines 17 goals aimed at ending poverty, protecting the planet, and ensuring prosperity for all. It addresses challenges such as climate change, inequality, and peace and justice. The agenda emphasizes the importance of partnerships, data, and financing in achieving these goals. Implementing the agenda requires a collective effort from governments, businesses, civil society, and individuals to create a more sustainable and equitable world by the year 2030.

Global Health and the Foreign Policy Agenda

Global health initiatives are a vital component of foreign policy. Efforts to address healthcare challenges worldwide can improve international relations and promote stability. Investments in global health can yield benefits for both public health and diplomatic relations, demonstrating a commitment to global cooperation and solidarity. As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, prioritizing global health in foreign policy agendas is crucial for fostering a safer and more prosperous global community.

Regional water cooperation in the Arab – Israeli Conflict: A case study of the West Bank

The conflict between Israel and Arab countries, with several devastating wars, is about territory and land, and maybe just as crucially on the water that flows through that land. This dissertation, an analysis of the management of water in the West Bank, as a case study, seeks to underline the possibility of using soft power diplomacy, in addition to mediation and water cooperation, for a more collaborative kind of approach to the conflict.

Contemporary Diplomacy: Representation and Communication in a Globalized World

The text discusses how diplomacy has evolved in the present globalized world, focusing on representation and communication.

The complexification of the United Nations system

The United Nations system has become increasingly complex over time, with the addition of specialized agencies, funds, and programs working alongside the main intergovernmental bodies.

Development Co-operation Report 2015: Making Partnerships Effective Coalitions for Action

The text discusses the importance of effective partnerships and coalitions for action in development cooperation as outlined in the Development Co-operation Report 2015.

Outcome document of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development: Addis Ababa Action Agenda

The Addis Ababa Action Agenda outlines commitments made at the Third International Conference on Financing for Development to address global financial challenges and promote sustainable development.

The History and Politics of UN Security Council Reform

Dimitris Bourantonis, Assistant Professor of International Relations at the Athens University of Economics and Business and a well-published writer on the UN over many years, has provided a very valuable service for students of the world body by writing this short book.

Diplomacy at the UN

The message will provide insights about diplomacy at the United Nations.

Environmental Diplomacy: Negotiating More Effective Global Agreements

The text is likely an article discussing the importance of environmental diplomacy in negotiating effective global agreements.

Perspectives on Africa’s Integration and Cooperation from OAU to AU

The text provides insights on Africa's integration and cooperation from the OAU to the AU.

Message on Switzerland’s International Cooperation in 2013-2016

The text discusses Switzerland's international cooperation activities from 2013 to 2016.

We the Peoples: The Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century

The world did celebrate as the clock struck midnight on New Year’s Eve, in one time zone after another, from Kiribati and Fiji westward around the globe to Samoa. People of all cultures joined in—not only those for whom the millennium might be thought to have a special significance. The Great Wall of China and the Pyramids of Giza were lit as brightly as Manger Square in Bethlehem and St. Peter’s Square in Rome. Tokyo, Jakarta and New Delhi joined Sydney, Moscow, Paris, New York, Rio de Janeiro and hundreds of other cities in hosting millennial festivities. Children’s faces ref...

Ahead of the Curve? UN Ideas and Global Challenges

Ideas and concepts are arguably the most important legacy of the United Nations. Ahead of the Curve? analyzes the evolution of key ideas and concepts about international economic and social development born or nurtured, refined or applied under UN auspices since 1945. The authors evaluate the policy ideas coming from UN organizations and scholars in relation to such critical issues as decolonization, sustainable development, structural adjustment, basic needs, human rights, women, world employment, the transition of the Eastern bloc, the role of nongovernmental organizations, and global govern...

Hanging In There: The G7 and G8 Summit in Maturity and Renewal

The G7 and G8 summits have evolved over time, transitioning from a focus on economic issues to a broader range of global challenges. Despite criticism, they remain relevant due to their ability to adapt and address current issues like climate change and cybersecurity. The summits have provided a platform for dialogue and cooperation among world leaders, underscoring the importance of multilateralism in today's interconnected world.

Multilateral Conferences: Purposeful International Negotiation

The message will provide insights on the purpose and significance of multilateral conferences in facilitating international negotiations.

Organisational culture of UN agencies: The need for diplomats to manage porous boundary phenomena

The goal of this article is to introduce readers to the complexity of the organisational culture of UN agencies in order to limit possible misunderstandings about the functioning of the UN and its agencies and in order to make diplomatic interactions with UN agencies as efficient and as effective as possible.

Palestinian statehood diplomacy: The Palestinian UN bids of 2011-2012

The Palestinian Authority (PA) launched an intense diplomatic campaign to garner a supporting vote in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), which was finally realized in 2012 by an upgrade to a 'non member observer state', granting Palestine a set of new privileges. It represents a victory for Palestinian diplomacy and presents a model of statehood diplomacy that received support as much as criticism. It stirred discussions about statehood and state recognition, and exposed the limited success of international interventions in post-conflict state building efforts.

A History of the United Nations. Volume I: The Years of Western Domination 1945-1955

The United Nations was formed in 1945 with a focus on maintaining world peace and promoting cooperation among nations. Initially dominated by Western powers, the organization's structure and policies evolved over the years to address global challenges and represent a more diverse membership.

The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations

"The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations" is a thought-provoking and insightful book that delves into the realm of public diplomacy and its significance in the context of modern international relations. Authored by Jan Melissen, a renowned scholar in the field, this book offers a comprehensive analysis of the evolving nature of diplomacy and the growing importance of soft power.

The Milennium Development Goals Report 2015

The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015 reflects on the progress made towards achieving the eight goals set by world leaders in 2000. It highlights significant accomplishments in areas such as poverty reduction, child mortality, and access to clean water. However, challenges remain, including disparities among regions and persistent inequalities. The report emphasizes the need for continued efforts to address these issues and accelerate progress towards sustainable development.

The Greening of Machiavelli: The Evolution of International Environmental Policy

The Greening of Machiavelli: The Evolution of International Environmental Policy" discusses the transformation of environmental policy on a global scale, reflecting a shift towards sustainability and cooperation.

Renewing the United Nations System

Our object in this study is to analyse the present state of the UN 'system' and to suggest changes and reforms which might allow it to function in a more systematic and effective manner. This study is the fourth in a sequence analysing salient problems in the working of the United Nations system and recommending how to equip it better to meet the enormous challenges of a new era. Each study has benefited from the sponsorship and consistent encouragement of the Dag Harnrnarskjold Foundation (Uppsala, Sweden) and the Ford Foundation (New York, USA). The work began in 1989-1990 with issues ...

Coercive Cooperation: Explaining Multilateral Economic Sanctions

The text discusses how multilateral economic sanctions can be effective in coercing cooperation from targeted states by increasing the costs of noncompliance.

The inertia of Diplomacy

Diplomacy is used to manage the goals of foreign policy focusing on communication. New trends affect the institution of diplomacy in different ways. Diplomacy has received an additional tool in the form of the Internet. In various cases of interdependence and dependence interference in a country’s affairs is accepted. Multilateral cooperation has created parliamentary diplomacy and a new type of diplomat, the international civil servant. States and their diplomats are in demand to curb the excesses of globalization. The fight against terrorism also brought additional work for diplomac...

EspriTech de Genève

EspriTech de Genève, embodying the tech spirit of Geneva, focuses on responsible, human-centred AI that intertwines historical thought with modern governance and coding. Rooted in the city's rich thining and humanitarian heritage, it transforms classical values into practical AI applications. EspriTech de Genève is a technically and financially viable approach to AI transformation, moving from concept to actionable results in everyday technology use.

Global Warming and Global Politics

Global warming is a pressing issue with far-reaching consequences. It is crucial that global politics address this problem collaboratively, as it affects all nations and requires collective action. The impact of climate change is evident worldwide, and political leaders must prioritize sustainability and environmental protection in their policies. Cooperation on a global scale is necessary to combat the effects of global warming and ensure a sustainable future for all. Political decisions and policies have a significant impact on the environment, and it is essential for leaders to prioritize t...

China is waking up to the benefits of good diplomacy in Asia

China is realizing the advantages of effective diplomacy in Asia.

Multilateralism and the End of History

The essay delves into the significance of multilateralism in the post-Cold War era, exploring its role in shaping global politics during a time when some believed that the end of the Cold War marked the "end of history." It discusses how multilateralism has become a key feature in navigating international relations and addresses the challenges and opportunities associated with this cooperative approach to diplomacy. The essay concludes by emphasizing the continued relevance and potential of multilateralism in today's complex and interconnected world.

United Nations, Divided World, 2nd ed

The message is a placeholder and does not contain any actual content to summarize.

Reinventing NATO’s Public Diplomacy

In "Reinventing NATO's Public Diplomacy," the focus is on adapting NATO's communication strategies to engage with diverse audiences effectively. This entails addressing challenges such as information overload and the spread of disinformation, emphasizing the importance of credibility, transparency, and innovation in public diplomacy efforts. The article highlights the necessity for NATO to evolve its approach to public diplomacy to remain relevant in today's rapidly changing information landscape.

Global Environmental Politics

Global Environmental Politics discusses the intricate relationships between politics, society, and the environment. It delves into how political decisions impact environmental issues and how societal actions can influence political agendas regarding global environmental challenges. By examining the interplay between various stakeholders, policies, and power dynamics, the book sheds light on the complexities of environmental governance on a global scale.

Development Co-operation Report 2014: Mobilising Resources for Sustainable Development

The Development Co-operation Report 2014 emphasizes the importance of mobilizing resources for sustainable development. It highlights the need for effective partnerships, innovative financing mechanisms, and increased transparency to achieve development goals. The report also stresses the importance of policy coherence, human rights-based approaches, and the engagement of a wide range of stakeholders in development efforts.

The ‘Working’ Non-Aligned Movement: Between Belgrade, Cairo, and Baku – The NAM’s Leadership Visibility

The objective of this chapter is to highlight lessons learned, promote best practices, and carry takeaways that are useful for other levels of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), or even other forums.

Regionalism versus Multilateralism

The literature on regionalism versus multilateralism is growing as economists and political scientists grapple with the question of whether regional integration arrangements are good or bad for the multilateral system. Are regional integration arrangements "building * blocks or stumbling blocks," in Jagdish Bhagwati's phrase, or stepping stones toward multilateralism?

5th MIKTA Foreign Ministers’ Meeting: Joint Communiqué

The Joint Communiqué issued at the 5th MIKTA Foreign Ministers' Meeting emphasizes the commitment to enhancing cooperation in various fields such as global health, climate change, sustainable development, and peace and security. The document reaffirms support for a rules-based international order, multilateralism, and the United Nations. MIKTA members also expressed solidarity in addressing challenges brought by the COVID-19 pandemic and agreed on the importance of equitable global vaccine distribution. The meeting highlighted the significance of promoting regional peace and stability, unders...

The Parliament of Man: The Past, Present and Future of the United Nations

The United Nations, established in 1945, aims to promote peace, security, and cooperation among countries worldwide. It provides a platform for global dialogue and decision-making on various issues, striving to uphold human rights and international law. While facing challenges and limitations, the UN continues to play a crucial role in addressing global challenges and advocating for a more peaceful and sustainable world.

Governance fore Health in the 21st Century: A study conducted for the WHO Regional Office for Europe

The study conducted for the WHO Regional Office for Europe focuses on governance for health in the 21st century.

How should the WHO reform: An analysis and review of literature

The WHO should focus on enhancing its governance structure, accountability, and flexibility to effectively address global health challenges. Strengthening collaboration with other organizations, improving funding mechanisms, and prioritizing transparency and inclusivity are crucial for successful reform.

International Relations and Global Climate Change

International relations play a crucial role in addressing global climate change. Cooperation among nations is essential to develop and implement effective solutions to combat climate change. Additionally, international agreements like the Paris Agreement serve as frameworks for countries to work together towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating the impacts of climate change on a global scale. By fostering collaboration and sharing resources, countries can make significant progress in the fight against climate change.

Negotiating the Balkans: The Prenegotiation Perspective

The issues, the activities and the relations preceding the formal international negotiations have increasingly become an area of a special theoretical interest.

Preventive Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: Redefining the ASEAN Way

Preventive Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: Redefining the ASEAN Way" discusses how ASEAN can enhance preventive diplomacy to address conflicts and maintain stability in the region. It emphasizes the need for early intervention, building trust among member states, and utilizing a regional approach to prevent conflicts before they escalate. The author advocates for a proactive and inclusive approach to diplomacy to uphold peace and security in Southeast Asia.

Valletta Statement on Multilateral Trade

The Valletta Statement on Multilateral Trade emphasizes the importance of a rules-based multilateral trading system in fostering sustainable development and economic growth. It calls for the preservation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) as the cornerstone of global trade governance. The statement stresses the need for WTO reform to address current challenges, defend against protectionism, and ensure that the organization remains responsive to the evolving needs of its members. It highlights the significance of multilateral cooperation in promoting a level playing field for all countries a...

Diplomacy with a Difference: The Commonwealth Office of High Commissioner, 1880-2006

Book review by Geoff Berridge

A New Diplomacy for Sustainable Development: The Challenge of Global Change

The text discusses the need for a new diplomacy approach to address the challenges of global change and foster sustainable development.

The Environmental Movement in the Global South

The message explores the environmental movement in the Global South, focusing on the challenges faced and the strategies employed to address environmental issues in developing countries.

How Much is a Seat on the Security Council Worth? Foreign Aid and Bribery at the United Nations

Ten of the fifteen seats on the U.N. Security Council are held by rotating members serving two-year terms. We find that a country’s U.S. aid increases by 59 percent and its U.N. aid by 8 percent when it rotates onto the council. This effect increases during years in which key diplomatic events take place (when members’ votes should be especially valuable) and the timing of the effect closely tracks a country’s election to, and exit from, the council. Finally, the U.N. results appear to be driven by UNICEF, an organization over which the United States has historically exerted great ...

Saving the Mediterranean: The Politics of International Environmental Cooperation

The text discusses the complexities of international environmental cooperation in the Mediterranean region, focusing on the political aspects involved in efforts to save the environment.

Small States at the United Nations

The proliferation of small states in the past few decades has brought small and larger states on the same playing field. Their increase in number triggered a wave of studies, raised concern by 'realists' and some powerful states, and led to an affirmation that at the United Nations, all states are equal, regardless of size.

The Charter of the United Nations: A Commentary

The Charter of the United Nations: A Commentary offers an in-depth analysis of the United Nations Charter. It explores the history, structure, and principles of the Charter, highlighting its role in promoting peace and cooperation among nations. The commentary also delves into the Charter's provisions on issues such as human rights, security, and international law, providing valuable insights for scholars, diplomats, and practitioners in the field of international relations.

EU Strategy for Africa

The EU Strategy for Africa aims to strengthen partnerships with African countries through political dialogue and cooperation on various issues, including peace and security, migration, trade, and investment. It prioritizes sustainable development, job creation, green growth, and digitalization to foster a mutually beneficial relationship between the EU and Africa. By working together, the EU and African countries can address common challenges, promote prosperity, and achieve shared goals for the benefit of both regions.

The challenge of regionalism

The challenge of regionalism is to balance the benefits of local autonomy with the need for cooperation and unity on broader issues. It seeks to foster collaboration among neighboring areas while respecting their unique identities and interests. Regionalism aims to address common challenges and opportunities through shared goals and strategies, promoting sustainable development and collective well-being. It requires finding a delicate equilibrium between fostering regional cohesion and preserving individual identities, all while working towards common objectives for the greater good of the reg...

The Diplomacy of Micro States

The message explores how small states navigate the world of international diplomacy and form strategic alliances to maximize their influence.

The latest from Diplo and GIP

Tailor your subscription to your interests, from updates on the dynamic world of digital diplomacy to the latest trends in AI.

Subscribe to more Diplo and Geneva Internet Platform newsletters!

Diplo: Effective and inclusive diplomacy

Diplo is a non-profit foundation established by the governments of Malta and Switzerland. Diplo works to increase the role of small and developing states, and to improve global governance and international policy development.