First, his birth was illegitimate, so the records of his early life are either largely fictitious or non-existent. Second, because he was a whistleblower but relatively impecunious, he went to great lengths to cover his own literary tracks in order to safeguard his salaried income, so it is by no means easy to identify his writing, especially his newspaper articles. Third, because aristocrats both inside and outside the Foreign Office were desperate to contrive his downfall a whole raft of damaging myths was created about his official conduct and particular events in his life, and these have been constantly re-cycled – and inevitably embellished. … Finally, he left no personal collection of private papers – no private correspondence, no diaries, no unpublished memoirs…

Berridge closes his book with these words:Grenville-Murray’s ultimate misfortune was that his two great patrons, Dickens and Palmerston, tugged him in opposite directions: the former to the literary exposure of social evils, the latter to the important work of diplomacy. He was no saint but it remains to his credit that, despite the tension between them and the strain that simultaneously plying these two trades imposed on his family, he made such a valuable contribution to both over such a long period. He deserves a better place in history than that pegged on the lazy re-cycling of the myths that he was a ‘scurrilous’ journalist deservedly ‘horsewhipped’ by a nobleman he had offended.

Two observations about this lively chronicle of an extraordinary life in diplomacy and journalism: first, its contemporary relevance (you can’t help noticing the partial parallels with another equally talented Murray whose controversial diplomatic career was eventually terminated by a hostile and exasperated Foreign Office); and, secondly, what an excellent film could be made of Berridge’s book, one that would be exciting and funny in equal parts. Conversion of the text to a film script wouldn’t be exceptionally difficult. It might need a voice-over narrator for which Geoff Berridge’s own distinctive voice would be ideal. In the introduction to his book on his own website, Berridge sets out no fewer than 16 reasons for his decision to publish it as an ordinary PDF file on his website rather than submitting it to his publishers for publication as a book, whether in hard covers, as a paperback or as an e-book, or any combination of the three. All book publishers should take the precaution of thinking carefully about the professor’s 16 reasons, which have significant lessons for them. The downside seems to be the greater difficulty in spreading awareness of the existence of the book on a single semi-private website: very little chance of reviews in specialist or general interest journals or newspapers, no mentions in publishers’ lists or advertisements. It’s there, absolutely free and ready to be downloaded, but how many people know about it? It’s even quite easy to send it from one’s own computer to a Kindle, if you have a Kindle account, so that you can add it to your Kindle library to read on the train, or plane, or in your favourite Chinese restaurant when lunching or dining alone. So please heed this earnest plea: if you’re prompted by this to download and read A Diplomatic Whistleblower in the Victorian Era, and if you enjoy it as much as I did, spread the word about it, and send your friends and family without delay to https://grberridge.diplomacy.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/GrenvilleMurray.01.pdf. PS: Full disclosure: Geoff Berridge is an old friend. A few years ago I made some modest contributions as Editorial Consultant to the first edition of his extraordinarily useful and readable Dictionary of Diplomacy: please see the Preface to the First Edition in subsequent editions. More recently he has proved an excellent mentor and literary godfather helping in very many ways to bring my own first (and last) book, What Diplomats Do, into a not particularly startled world — please see https://www.barder.com/4229. Note: Review was first published on Brian Barder’s website and is reposted here with permission from the author. Review by Brian BarderYou may also be interested in

Twentieth-Century Diplomacy: A Case Study of British Practice, 1963-1976

Some years ago, John Young, Professor of International History at the University of Nottingham and long-serving Chair of the British International History Group, turned his thoughts and research in the direction of diplomatic procedure. This is the first monograph to be the product of his shift in direction and it is to be most warmly welcomed. It is original in focus, impeccably researched (private papers and oral history transcripts have been sifted as well official documents in The National Archives), crisply written, and altogether a major contribution to the contemporary history of diplom...

A Diplomatic Whistleblower in the Victorian Era: The Life and Writings of E. C. Grenville-Murray, Second Edition (Revised) 2015

Unlike Bradley Manning and Edward Snowden, the most well-known whistleblowers of the present day, Eustace Clare Grenville-Murray (1823-1881), the illegitimate son of an English duke and an actress who was also a lover of Lord Palmerston, did not make public highly classified documents. Instead, while serving as a diplomat behind the fragile shield of anonymity, he employed satire and ridicule in books, periodicals, and newspapers to attack the aspects of diplomacy he disliked.

DC Confidential: The controversial memoirs of Britain’s ambassador to the U.S. at the time of 9/11 and the Iraq War

DC Confidential: The controversial memoirs of Britain's ambassador to the U.S. at the time of 9/11 and the Iraq War.

The Architecture of Diplomacy: Building America’s Embassies, 2nd ed

The Architecture of Diplomacy: Building America's Embassies, 2nd ed. explores the intricate design process behind creating US embassies worldwide, showcasing the significance of architecture in diplomacy and international relations. It delves into the cultural, historical, and political considerations that shape embassy structures, emphasizing the crucial role architecture plays in representing American values and promoting diplomatic relationships globally. This revised edition offers a comprehensive look at the evolving architectural landscape of US embassies and the impact of design on dipl...

The ‘Working’ Non-Aligned Movement: Between Belgrade, Cairo, and Baku – The NAM’s Leadership Visibility

The objective of this chapter is to highlight lessons learned, promote best practices, and carry takeaways that are useful for other levels of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), or even other forums.

Amarna Diplomacy: A Fully-fledged Diplomatic System in the Near East?

The text analyses diplomatic relations during the Amarna period in ancient Egypt, examining the structure, protocols, and effectiveness of the diplomatic system in facilitating communication and negotiation among the various Near Eastern powers of the time.

Diplomacy with a Difference: The Commonwealth Office of High Commissioner, 1880-2006

Book review by Geoff Berridge

The Congress of Arras, 1435

The Congress of Arras in 1435 was a diplomatic gathering aimed at negotiating peace between France and Burgundy after years of conflict. The congress resulted in the Treaty of Arras, in which Burgundy agreed to abandon its alliance with England and recognize the authority of the French king, Charles VII, thus contributing to the eventual reunification of France under his rule. This diplomatic achievement marked an important step towards ending the Hundred Years' War and establishing a more unified France.

Diplomacy in Ancient Greece

The text discusses ancient Greek diplomacy, highlighting the significance of alliances, treaties, and negotiations in maintaining peace and balance of power among city-states. It also mentions the practice of sending envoys to conduct diplomatic missions and the use of oratory skills to influence decisions in the Greek world. Diplomacy played a crucial role in managing conflicts, resolving disputes, and fostering relationships between city-states in Ancient Greece.

The Cinderella Service: British Consuls since 1825

The British Consul Service has evolved over the years since 1825, adapting to modern times while maintaining its traditional values and responsibilities.

The First Resort of Kings: American cultural diplomacy in the twentieth century

The text discusses the significance of American cultural diplomacy throughout the twentieth century, highlighting its role as an essential tool for promoting American values and influence on a global scale.

Twentieth Century Diplomacy: A case study of British practice, 1963-1976

The book review discusses a case study of British diplomacy from 1963 to 1976. It delves into various diplomatic methods employed during this period, such as resident embassies, special missions, summitry, state visits, and dealing with unfriendly governments. The study highlights the importance of traditional diplomatic practices alongside newer forms, showing how they complement rather than compete with each other. The review praises the book's thorough research and insightful analysis, suggesting it as a model for enhancing understanding of diplomatic practices in different contexts.

The languages of the Knights

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): In his examination of the languages used by the Knights of St John in Rhodes and Malta during the 14th to 16th centuries, Professor Joseph Brincat applies the methodology of historical linguistics. As an international and multi-lingual entity, the Order faced difficulties with its administrative methods intimately linked to linguistic issues.

British Diplomacy and the Descent into Chaos: The career of Jack Garnett, 1902-19

I am in favour of biographies of relatively obscure individuals like Jack Garnett because there are plenty of them on the famous; moreover, studies of this kind often turn up interesting details (including how the famous were seen from the foothills) and stimulate thought on bigger questions. John Fisher’s well written and thoroughly researched study of this early twentieth century British diplomat, into which contextual detail is expertly woven, is no exception.

The Falkland Islands War: Diplomatic Failure in April 1982

The text discusses how the Falkland Islands War of April 1982 was a diplomatic failure.

Diplomacy at the Highest Level: The Evolution of International Summitry

The text discusses the evolution of international summitry and how it has become a key tool for diplomacy at the highest levels.

Politics and Culture in International History, 2nd ed

The message focuses on the interactions between politics and culture in international history, emphasizing its complexities and interconnected nature. It delves into how political decisions and cultural aspects influence each other, shaping the course of international relations.

Gerals Firzmaurice (1965-1939), Chief Dragoman of the British Embassy in Turkey

Gerals Fitzmaurice (1865-1939) was the Chief Dragoman of the British Embassy in Turkey.

The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey

If God ever gave mankind a mission – it was not so much to multiply as to walk. And walk we did, to the farthest corners of the earth. Homo sapiens sapiens is the only mammal to have spread from its place of origin, Africa, to every other continent – before settling down to sedentary life ogling a TV screen or monitor, that is.

The Summer Capitals of Europe, 1814-1919

This is an original work, meticulously researched, rich in detail, and written in a clear and – here and there – refreshingly pungent style. Soroka is a Russian scholar but at ease in English.

The Breaking of Nations

Robert Cooper is Director-General of External and Politico-Military Affairs for the Council of the EU and thus a man steeped in world affairs. Though he makes no claim to establishing a ‘theory’ of how nations grow and decay, he has presented in this slim volume a rigorous typology of today’s nations. His thoughts are worth setting out in some detail.

Curing the Sick Man: Sir Henry Bulwer and the Ottoman Empire, 1858-1865

This is the first book of a very promising young historian. Laurence Guymer, who is head of the Department of History at Winchester College and a research associate in the School of History at the University of East Anglia, has produced a biography of Sir Henry Bulwer that successfully challenges the conventional account of this colourful mid-Victorian figure. It also raises the question of how ‘diplomatic success’ is judged.

The Dust of Empire: The Race for Mastery in the Asian Heartland

Central Eurasia refers to the countries in the Caucasus and to the five countries of Central Asia: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. These countries that had once been part of the Russian and Soviet Empire were broken off and set adrift when the Soviet Union self-destructed at the end of 1991. They belatedly joined Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran, three countries that also emerged from the sphere of influence of an empire, the British one, to become – in the words of Charles De Gaulle speaking of the newly independent African states – the dust of empire.

The Diplomacy of Ancient Greece – A Short Introduction

Employed against a warlike background, the diplomatic methods of the ancient Greeks are thought by some to have been useless but by others to have been the most advanced seen prior to modern times.

A New Generation Draws the Line: Kosovo, East Timor and the Standards of the West

Note: The author of this review compares Noam Chomsky's A New Generation Draws the Line: Kosovo, East Timor and the Standards of the West and David Fromkin's Kosovo Crossing: American Ideals meet Reality on the Balkan Battlefields.

The Queen’s Ambassador to the Sultan: Memoirs of Sir Henry A. Layard’s Constantinople Embassy, 1877-1880

Once more students of Ottoman diplomatic history are in debt to the scholar-publisher, Sinan Kuneralp, for Sir Henry Layard was one of the most remarkable and controversial of British ambassadors to Turkey in the nineteenth century and served there during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-8 – and yet the volumes of his memoirs dealing with this period have hitherto languished unpublished in the British Library, in part perhaps because of their size. (Layard admits himself to having been ‘somewhat minute, perhaps a great deal too much so’, p. 692.)They are here published almost in their entir...

The origins, use and development of hot line diplomacy

The text is about the history, usage, and evolution of hot line diplomacy.

Renaissance Diplomacy and the Reformation

We invite you to continue our walk along timeline of Evolution of diplomacy and technology. In May, our next stop is Renaissance diplomacy and the impact of the invention of the printing press on diplomacy in the Reformation period.

Machiavelli’s Legations

The text provided for summarization appears to be missing. Could you please provide the content you would like summarized?

Studies in Dipomatic History and Historiography in honour of G. P. Gooch, C. H.

This book is a tribute to G. P. Gooch, exploring the realms of Diplomatic History and Historiography through a collection of studies.

The History of Diplomatic Immunity

This is a massive book in more than one sense. It is over 700 pages long, including an invaluable bibliography which itself stretches over 70 pages. While dwelling chiefly on the Western tradition, it also takes in the Ottoman Empire and the Far East.

Room for Diplomacy: The history of Britain’s diplomatic buildings overseas, 1800-2000

Mark Bertram joined the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works after reading architecture at Cambridge and remained in the civil service as architect, project manager, administrator, estate manager and – in his own words – ‘quasi diplomat’ for the next thirty years.

The Rise of Modern Diplomacy, 1450-1919

The text discusses how modern diplomacy evolved between 1450 and 1919, highlighting the changes in diplomatic practices, the emergence of new diplomatic actors, and the impact of historical events on diplomacy during this period.

Strategic Public Diplomacy: The Evolution of Influence

Strategic Public Diplomacy: The Evolution of Influence" explores the development of public diplomacy strategies, focusing on their impact and evolution over time.

Secret Channels: The Inside Story of Arab-Israeli Peace Negotiations

Secret Channels: The Inside Story of Arab-Israeli Peace Negotiations" delves into the clandestine negotiations that paved the way for peace agreements between Arab nations and Israel. It provides insight into the complexities, challenges, and breakthroughs that occurred during these diplomatic efforts, offering a behind-the-scenes look at the intricate process of brokering peace in the Middle East.

Nation, Class, and Diplomacy: The dragomanate of the British embassy in Constantinople, 1814-1914

In Markus Msslang and Torsten Riotte (eds.), The Diplomats’ World: A Cultural History of Diplomacy, 1815-1914 (Oxford University Press for the German Historical Institute, London: Oxford and New York, 2008), pp. 407-31

The Forgotten French

The text discusses the impact and significance of French immigrants on American history and culture, highlighting their contributions and accomplishments that are often overlooked or forgotten.

Years of Upheaval

The text discusses the challenges and changes experienced over several years.

Under the Wire: How the telegraph changed diplomacy

Nickles, who is a State Department historian, has written the first full-length study of this important and intriguing subject. Excluding an introduction and short conclusion, it has seven chapters presented in three parts ('Control', 'Speed', and 'The Medium'), each having a chapter devoted to a case study: the Anglo-American crisis of 1812, the further Anglo-American crisis of 1861 ('the Trent affair'), and the Zimmerman telegram of January 1917 - which of course also involved the United States.

International Diplomacy Volume III: The Pluralisation of Diplomacy

The message is not present.

Guicciardini on Diplomacy: Selections from the Ricordi

Guicciardini reflects on diplomacy, emphasizing the importance of discretion, understanding the motives of others, and the necessity of adapting strategies based on changing circumstances. Diplomats should aim to achieve favorable outcomes while safeguarding their state's interests.

The Secret History of Dayton: U.S. Diplomacy and the Bosnia Peace Process 1995

The Secret History of Dayton: U.S. Diplomacy and the Bosnia Peace Process 1995 recounts the behind-the-scenes negotiations and strategies employed by American diplomats during the Dayton Peace Accords that ended the Bosnian War. The U.S. played a crucial role in brokering peace between the warring factions and outlining the terms of the agreement that led to the successful resolution of the conflict.

FDR’s Ambassadors and the Diplomacy of Crisis: From the rise of Hitler to the end of World War II

What effect did personality and circumstance have on US foreign policy during World War II? This incisive account of US envoys residing in the major belligerent countries – Japan, Germany, Italy, China, France, Great Britain, USSR – highlights the fascinating role played by such diplomats as Joseph Grew, William Dodd, William Bullitt, Joseph Kennedy and W. Averell Harriman. Between Hitler's 1933 ascent to power and the 1945 bombing of Nagasaki, US ambassadors sculpted formal policy – occasionally deliberately, other times inadvertently – giving shape and meaning not always intended by ...

Getting Our Way: 500 Years of Adventure and Intrigue: The Inside Story of British Diplomacy

The message summarizes the book "Getting Our Way: 500 Years of Adventure and Intrigue: The Inside Story of British Diplomacy.

The Practice of Diplomacy: Its evolution, theory and administration

First published in 1995, the long-awaited second edition of this valuable textbook on the history of diplomacy has at last appeared. The first chapter has been expanded to include non-European traditions, and a wholly new chapter has been added to take account of developments over the last 15 years. It is for the main part a work of relaxed authority, clearly written, and – unusually for an introductory work – full of intriguing detail which it would be difficult if not impossible to find in other secondary sources.

Finance, Trade and Politics in British Foreign Policy, 1815-1914

The text explores the interplay of finance, trade, and politics in British foreign policy from 1815 to 1914. It discusses how economic factors influenced decision-making and shaped diplomatic relations during this period.

Lord Elgin and the Marbles

The text provides a thorough examination of the controversy surrounding Lord Elgin's acquisition of the Parthenon Marbles, offering insights into the historical, cultural, and ethical dimensions of their removal from Greece to Britain.

A History of Diplomacy in the International Development of Europe, vol. 1

Although special questions and particular periods of diplomatic history have been carefully studied and ably discussed by historical writers, it is a noteworthy fact that no general history of European diplomacy exists in any language.

The Ambassadors: From Ancient Greece to the Nation State

The Ambassadors: From Ancient Greece to the Nation State explores the historical role of ambassadors, tracing their origins in ancient Greece through to the present day practices of representing nations on the international stage. The book delves into the evolution of diplomacy, the duties and responsibilities of ambassadors, as well as the impact they have had on shaping the relations between states throughout history. Through a detailed examination of the development of diplomatic protocols and practices, readers gain insight into the crucial role ambassadors play in promoting peace, resolvi...

The History of Diplomatic Immunity

A thorough and extensive book on diplomatic immunity covering Western tradition, the Ottoman Empire, and the Far East. It provides a comprehensive historical overview, but its heavy reliance on examples and cases sometimes clouds key ideas. The authors occasionally overemphasize reciprocity's role in diplomatic relations, overlooking other significant factors. The book also paints a bleak picture of late 20th-century diplomacy, neglecting positive aspects like the strengthening of the international system. Despite some flaws, the reviewer recommends it to students.

Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana

The book "Back Channel to Cuba" discusses the negotiations between Washington and Havana, leading up to the historic announcement of the normalization of relations in December 2014. The authors highlight the failed methods employed by the U.S. in dealing with Cuba and emphasize the importance of common interests in facilitating diplomatic discussions. The book provides a detailed account of the various forms of "back-channel" diplomacy utilized, showcasing the intricate negotiations between the two countries. Despite some criticisms of the structure of the book, the work is considered richly d...

Blundering Into Disaster: Surviving the First Century of the Nuclear Age

Blundering Into Disaster: Surviving the First Century of the Nuclear Age" discusses the history of nuclear weapons, their impact on global politics, and the potential threats they pose to humanity. The book explores past nuclear incidents and the dangers of accidental nuclear conflict, emphasizing the need for responsible decision-making to prevent catastrophic outcomes.

Side-Lights on English Society, or Sketches from Life, Social and Satirical

The text provides insight into English society through social and satirical sketches from daily life.

The Collision of Two Civilisations: The British Expedition to China 1792-4

The text discusses the British expedition to China in 1792-94, examining the clash between two cultures.

The Imperial Component in Iran’s Foreign Policy: Towards Arab Mashreq and Arab Gulf States

One of the most important developments the Middle East has witnessed in the 20th centaury was the success of the Iranian revolution of Islamist ideology, with ambitions to control.

Back Channel to Cuba: The hidden history of negotiations between Washington and Havana

This book went to press after the much-publicised handshake between US president Barack Obama and Cuban president Raul Castro at the memorial service for Nelson Mandela in December 2013 – but before their historic, simultaneous announcements a year later, assisted by a prisoner exchange and the good offices of the Vatican, that they were resolved to end their 50 years of estrangement and normalise relations.

International Diplomacy Volume IV: Public Diplomacy

The text explores the domain of public diplomacy within the broader context of international diplomacy, offering insights into the evolving strategies and practices of statecraft aimed at engaging and influencing foreign publics.

The Counter-Revolution in Diplomacy, and Other Essays

This book brings together for the first time a large collection of essays (including three new ones) of a leading writer on diplomacy. They challenge the fashionable view that the novel features of contemporary diplomacy are its most important, and use new historical research to explore questions not previously treated in the same systematic manner.

Just a Diplomat

Close students of the new, Conservative Party Mayor of London, the at once engaging and alarming Boris Johnson, will know that he has Turkish cousins. One of these is Sinan Kuneralp, a son of the late Zeki Kuneralp, probably the most distinguished and well liked Turkish diplomat of his generation. Sinan Kuneralp is a scholar-publisher and runs The Isis Press in Istanbul, a house at the forefront of publishing scholarly works and original documents on the Ottoman Empire, chiefly in English and French. The three works noticed here are all its products and reflect the publisher’s own special in...

English dragomans and oriental secretaries: the early nineteenth-century origins of the anglicization of the British embassy drogmanat in Constantinople

The text discusses the early 19th-century origins of the anglicization of the British embassy drogmanat in Constantinople, focusing on English dragomans and oriental secretaries.

Instruzione e formazione del diplomatico: la tradizione inglese

The text discusses English traditions in diplomatic instruction and training.

A kind of diplomatic incantation: Exchanging British and Japanese diplomats in the Second World War

The content discusses how British and Japanese diplomats were exchanged during World War II in a diplomatic ritual that followed strict protocols to ensure the safety and respect of both parties.

To Begin the World Anew: The Genius and Ambiguities of the American Founders

When I feel dispirited about the current crop of political leaders in Switzerland or around the world, I like to take refuge in one of the most uplifting political stories of mankind – the American Revolution.

History and the evolution of diplomacy

Update: Visit our page on History of Diplomacy and Technology, where we try to discover how civilizations dealt with ‘new’ technologies, from simple writing, via the telegraph, to the internet.

A Diplomatic Whistleblower in the Victorian Era

It’s not often that a fascinating and important new book — in this case about an accomplished diplomat, journalist, whistle-blower, novelist, dissembler and controversial celebrity of Victorian times — is made available, totally free of charge, to anyone with a computer, internet access and Adobe software for downloading a book-length PDF file. This is what Professor Emeritus G R Berridge, prolific writer and author of the classic textbook Diplomacy: Theory and Practice, has done with his latest book, A Diplomatic Whistleblower in the Victorian Era: The Life and Writings of E. C. ...

British Diplomacy in Turkey, 1583 to the Present: A Study in the Evolution of the Resident Embassy

The text discusses the evolution of the resident embassy in Turkey from 1583 to the present, focusing on British diplomacy in the region. It delves into the historical development and changes in diplomatic practices over time.

The Office of Ambassador in the Middle Ages

The text discusses the role and responsibilities of an ambassador in the Middle Ages. It touches upon the importance of diplomatic skills, cultural awareness, and the power dynamics involved in representing a kingdom or ruler in foreign territories. The text emphasizes the ambassador's role in negotiation, communication, and fostering positive relationships to advance their country's interests.

The Ambassadors and America’s Soviet Policy

The Ambassadors and America's Soviet Policy discusses the roles of three prominent American ambassadors in shaping U.S. policy towards the Soviet Union during the early Cold War period. These diplomats employed various strategies to navigate the complexities of Soviet-American relations, including engaging in diplomacy, intelligence gathering, and negotiation. Overall, their efforts helped influence U.S. foreign policy towards the Soviet Union and contributed to the eventual end of the Cold War.

Guicciardini’s Ricordi: The Counsels and Reflections of Francesco Guicciardini

Francesco Guicciardini was born into a long-established patrician family in Florence in 1483. He trained and then practised successfully as a lawyer, but in January 1512 was sent by the signoria, despite his youth, as ambassador to Spain.1 His mission was conducted against a background of acute tension and at a time when the goodwill of Ferdinand the Catholic — that master of deceit’ 2 — was of the first importance to the republic. (Ferdinand’s soldiers, only recently allied to those of Pope Julius II against Florence’s ally, France, were entering the nearby Romagna.) Guicciardini re...

The Washington Embassy: British ambassadors to the United States, 1939-77

The Washington Embassy: British ambassadors to the United States from 1939 to 1977 examines the role and impact of British ambassadors in the United States during this time period.

British Envoys to Germany 1816-1866

The text discusses the role and activities of British envoys in Germany from 1816 to 1866.

Diplomacy with a Difference: The Commonwealth Office of High Commissioner, 1880-2006

In writing her history of the origins and evolution of the office of high commissioner, Dr Lloyd, who is a Senior Lecturer in International Relations at Keele University, has drawn on a vast range of sources. She has sifted through archives of public and private papers not just in Britain but in Ireland, Canada, and South Africa; and she has conducted many interviews and much correspondence with former high commissioners.

The British Diplomatic Service 1815-1914

The British Diplomatic Service from 1815 to 1914 showcases the evolution of a prestigious institution that adapted to the changing political landscape of the 19th century. This period saw the service expand its reach globally, employing both traditional aristocratic diplomats and a growing number of professionals. The diplomatic corps played a vital role in maintaining British interests abroad, while facing challenges such as increased international competition and demands for specialized knowledge. The period also witnessed the professionalization of diplomatic practices and the development o...

Diplomatic integration with Europe before Selim III

The text explores the historical dynamics and mechanisms of diplomatic integration between European powers and the Ottoman Empire before the era of Selim III, examining the factors, strategies, and challenges involved in this complex process of diplomatic engagement and interaction.

The Argentine seizure of the Malvinas [Falkland] Islands: History and Diplomacy

The Argentine seizure of the Malvinas [Falkland] Islands is a historical event that involves complex diplomatic implications.

U.S. Propaganda in the Middle East – The Early Cold War Version

The text discusses the use of U.S. propaganda in the Middle East during the early Cold War era.

Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World

Ask anyone who was the person that most influenced world history: few would mention Genghis Khan. Arguably, however, Genghis Khan and the Mongols were the dominant force that shaped Eurasia and consequently the modern world. Not for what they destroyed – though they wrought much destruction all over the continent – but for what they built. They came close to uniting Eurasia into a world empire, and in so doing they spread throughout it technologies like paper, gunpowder, paper money, or the compass – and trousers. They revolutionised warfare. More lastingly, in the words of the author: '...

Notes on the origins of the diplomatic corps: Constantinople in the 1620s

The diplomatic corps in Constantinople during the 1620s played a crucial role in diplomatic activities, managing relationships with foreign powers, facilitating negotiations, and gathering intelligence. The ambassadors stationed there were required to navigate complex political landscapes, cultural differences, and personal rivalries. This era marked the beginning of professionalized diplomacy, where ambassadors were trained in the art of negotiation and represented their countries' interests with skill and tact.

A History of Diplomacy in the International Development of Europe, vol. 3

The text provided was empty. Could you please provide the content you would like to be summarized?

Diplomacy and Power: Studies in Modern Diplomatic Practice

The text explores the complex relationship between diplomacy and power, analysing their interconnectedness and interactions on the global stage.

The Power of Small States: Diplomacy in World War II

This Is an inquiry into how the governments of small and militarily weak states can resist the strong pressure of great powers even in crisis periods. The continued existence and, in deed, startling increase in the number of small states may seem paradoxical in the age of superpowers and the drastically altered ratio of military strength between them and the rest of the world. It is well known that the ability to use violence does not alone determine the course of world politics. Some of the other determinants can be observed with exceptional clarity in the diplomacy of the small ...

The Origins of the Diplomatic Corps: Rome to Constantinople

The evolution of the diplomatic corps can be traced back to ancient Rome, where envoys played a key role in maintaining relationships with other civilizations. As the Roman Empire transitioned to Constantinople, the concept of diplomatic missions continued to develop, becoming more formalized and structured. From humble beginnings in Rome to the sophisticated diplomatic corps of Constantinople, the foundations of modern diplomacy were laid, shaping the interactions between nations for centuries to come.

Byzantine Diplomacy: Papers of the Twenty-fourth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies

A detailed examination of Byzantine diplomacy, from its emergence to its fall to the Ottoman Turks, is presented in the collection of papers from the 24th Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies held in 1990 in Cambridge. The volume covers political relations, societal aspects, and even includes a mysterious communication from an ancient emperor. Published on behalf of the Society for the Promotion of Byzantine Studies, this book is part of a series focusing on various aspects of Byzantine history.

Foreign ministries and the management of the past

In his paper, Keith Hamilton looks at Foreign Ministries’ treatment of historical diplomacy, and specifically, the publication of diplomatic documents. Through his historical analyses, the author examines the various aims of these documents, such as, to shed light on past developments and help in current and future negotiations; to influence parliamentarians and a wider public; and to further international relations’ studies.

Amarna Diplomacy: The Beginnings of International Relations

The text discusses the emergence of diplomatic relationships during the Amarna period, highlighting how this era marked the start of international relations.

Tilkidom and the Ottoman Empire: The Letters of Gerald Fitzmaurice to George Lloyd, 1906-15

Gerald Henry Fitzmaurice was Chief Dragoman at the British Embassy in Constantinople before the First World War and George Ambrose Lloyd was a young Honorary Attaché based in the Embassy from the autumn of 1905 until the end of 1906. In Gerald Fitzmaurice (1865-1939), which leans heavily on the private letters that Fitzmaurice wrote to Lloyd between 1906 and 1915, I describe the ups and downs of the close friendship which developed between them. I also deal more or less fully with many of the subjects raised in the letters. Why, then, publish them separately?

Misunderstood: The IT manager’s lament

Communication between information technologists and their clients – including diplomats - does not work as well as it should. We know that information technology has become ubiquitous. We also know that diplomats rely extensively on web services, electronic mail and documents in electronic form. Yet when communication does not work well, technologists poorly understand the needs of the diplomatic community. As a result, technical solutions may not address the real needs of end-users. This paper is a study on inter-professional miscommunication.

International Diplomacy Volume II: Diplomacy in a Multicultural World

The text discusses the importance of multiculturalism in diplomacy to achieve mutual understanding and cooperation among nations, emphasizing the significance of cultural sensitivity and respect in international relations.

Kautilya’s Arthasastra on war and diplomacy in Ancient India

Kautilya's Arthasastra offers insights into war and diplomacy in Ancient India, emphasizing strategic thinking, espionage, alliances, and statecraft.

The Professional Diplomat

The message provides guidance and advice on professionalism and diplomacy in interpersonal interactions. It emphasizes the importance of maintaining composure, being respectful, and considering others' perspectives in order to navigate social situations effectively.

The evolution of diplomacy in the Caribbean

This paper will focus on the development of diplomacy in the Caribbean and how it impacts the development of small Caribbean States, paying attention to the regional, bilateral and multilateral levels of diplomacy.

The Diplomats, 1939-1979

The message provides a brief overview of a diplomatic history spanning the years from 1939 to 1979.

A History of Diplomacy in the International Development of Europe, vol. 2

The message provides an overview of the evolution of diplomacy in Europe, highlighting its significance in international development.

The Evolution of Diplomatic Method

The Evolution of Diplomatic Method discusses the changing nature of diplomacy over time. From traditional methods to modern practices, diplomacy has adapted to technological advancements and global challenges. The article emphasizes the importance of evolving diplomatic strategies to effectively address the complexities of the contemporary world.

Diplomacy of Image & Memory: Swiss Bankers and Nazi Gold

The text discusses the perception of Swiss bankers in relation to their handling of Nazi gold during World War II.

Beyond diplomatic – the unravelling of history

In his paper, Robert Alston travels through time to rekindle an important highlight – as well as a personal highlight – in the history of knowledge management. His journey takes him back to the 1850s, which saw Antonio Panizzi’s efforts in creating a universal repository of knowledge in the British Museum; and to the 1990s, a time in which he acquired first-hand experience at the same museum, drawing conclusions on the various available ways of navigating large bibliographical and archival databases.

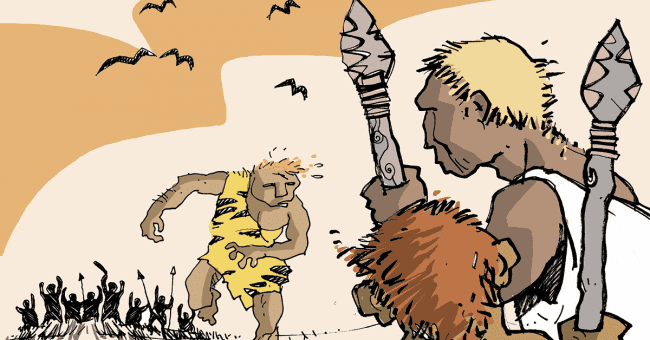

Searching for the prehistoric origins of diplomacy

What if diplomacy had started in the first contact between two distinct bands of nomadic Homo sapiens hunter-gatherers in the Palaeolithic period, even before the advent of agriculture and the transition from nomadism to Neolithic sedentary societies? In this post, prepared especially for this blog, a summary of the author’s argument, originally published by the Cambridge Review of International Affairs [1], is presented to DiploFoundation readers searching for the ancient origins of the diplomatic practice.

The British Interests Section in Kampala, 1976-7

The message below provides an overview of the activities and challenges faced by the British Interests Section in Kampala between 1976 and 1977.

The Invisible Weapon: Telecommunications and International Politics 1851-1945

The text discusses the impact of telecommunications on international politics from 1851 to 1945.

Public diplomacy: Sunrise of an academic field

The text discusses the emergence and growth of public diplomacy as a field of study within academia.

The Beijing-Washington Back-Channel and Henry Kissinger’s Secret Trip to China

The text discusses the Beijing-Washington back-channel and Henry Kissinger's covert visit to China.

Relations between Cyprus and Germany 1960 to 1968

Antonis Sammoutis attempts an examination of relations between Germany and Cyprus during the years 1960-1968. He starts by examining bilateral relations in the first three years of the Republic of Cyprus and then going into the most crucial year of the conflict in Cyprus - 1964. Sammoutis then examines the years 1965-1968 ending with a summary of the main issues along with the main conclusions drawn from the research.

England and the Avignon Popes: The practice of diplomacy in late medieval Europe

In England and the Avignon Popes, Karsten Plöger, who is a Research Fellow at the German Historical Institute in London, has provided an invaluable book not only for students of medieval diplomatic method but for students of diplomacy in general. It is a work of immense and meticulous scholarship: exhaustively researched, well organized, carefully worded, penetrating, and beautifully written.

Did diplomatic immunity exist in the ancient Near East?

The text discusses the concept of diplomatic immunity in the ancient Near East.

The Nineteenth Century Foreign Office

The Nineteenth Century Foreign Office discusses the evolution of foreign diplomacy during the 1800s, emphasizing the growth of Britain's diplomatic service, the influence of key diplomats and foreign secretaries, and the changing dynamics of international relations during this time period. It explores the impact of major events such as the Congress of Vienna, the Crimean War, and the development of the British Empire on the role and function of the Foreign Office. The article highlights the significant role played by diplomats and foreign secretaries in shaping British foreign policy and navig...

English Medieval Diplomacy

The text discusses English Medieval Diplomacy.

Summits: Six Meetings that Shaped the Twentieth Century

Summits: Six Meetings that Shaped the Twentieth Century" explores the impact of six key summits in the 20th century, highlighting their significance in shaping global politics and history. These meetings, involving world leaders like Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, and Kennedy, influenced major events such as the Cold War, arms control negotiations, and diplomatic relations. Through detailed analysis, the book demonstrates how these summits played a crucial role in shaping the geopolitical landscape of the 20th century.

The Diplomats, 1919-1939

The message outlines the diplomatic efforts and challenges between 1919 and 1939, exploring key events and agreements during this period.

The Expansion of International Society

The text discusses the expansion of international society, highlighting the growth and interconnectedness of nations, cultures, and people globally. It emphasizes the importance of understanding and embracing diversity in order to foster cooperation and mutual respect on a global scale.

Ottoman Diplomacy

In tne text "Ottoman Diplomacy," the Ottoman Empire's diplomatic practices are explored, focusing on their use of ambassadors, gifts, and protocol to maintain relationships with other powers. This diplomacy was essential to the empire's survival and success throughout its history.

Under the Wire: How the Telegraph Changed Diplomacy

Review by Geoff Berridge

Japanese middle-power diplomacy

In the realm of international relations, Japan engages in middle-power diplomacy, showcasing its influence and capabilities while fostering beneficial relationships on the global stage.

Politics and Diplomacy in Early Modern Italy: The structure of diplomatic practice, 1450-1800

This collection of essays, edited and well introduced by Daniela Frigo of the University of Trieste, reflects the comparatively recent rediscovery of interest in the diplomacy of their own peninsula by Italian historians. (The only non-Italian contributor is Christopher Storrs.) All of the essays are of a high standard and most contain much new research. Adrian Belton is, therefore, also to be congratulated for making them accessible to English readers by means of his excellent translation.

Peacemaking 1919

The message examines the peacemaking efforts of 1919, reflecting on the challenges faced during the time and lessons learned from the process.

King Cotton Diplomacy: Foreign Relations of the Confederate States of America

The text discusses the foreign relations strategy of the Confederate States of America known as King Cotton Diplomacy, which aimed to leverage the economic power of cotton to gain support from European nations during the Civil War.

A Manual of Greek Antiquities

Jevons and Gardner’s collaborative effort provides a fascinating glimpse into the fascinating world of ancient Greece, from its temples and sculptures to its social customs and religious practices.

Philosophy of Rhetoric

The author introduces a series of Essays on Rhetoric, explaining their origins and interconnection. This work has been a lifelong pursuit since 1750 and is structured based on a plan laid out in the first two chapters.

Post Cold War diplomatic training

Victor Shale's paper refers to a specific time period: the post-Cold War period which brought about new forms of conflicts, and high levels of terrorism. In the light of the change in traditional diplomacy, his paper examines multistakeholder diplomatic training and its importance as an approach in penetrating different cultures, and examines whether this approach could be used to minimise intractable conflicts.

The Turkish Embassy Letters

In "The Turkish Embassy Letters," the author describes her experiences during her stay in Turkey. She shares her observations on the culture, customs, and traditions of the Turkish people. Through her letters, she provides insight into the societal norms and interactions she encounters, offering a unique perspective on life in Turkey.

Documenting diplomacy, Evaluating documents: The case of the CSCE

Part of Language and Diplomacy (2001): Rather than individual documents, Dr Keith Hamilton looks at the process and purpose of compiling collections of documents. He focuses on his own experience as the editor of Documents on British Policy Overseas, and particularly on his work publishing a collection of documents concerning the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe from 1972 until 1975.

Bertie of Thame: Edwardian Ambassador

Explore the life of Bertie of Thame, an Edwardian ambassador, to gain insights into his diplomatic achievements and the impact he had on international relations during his time.

Munitions of the Mind: A history of propaganda from the ancient world to the present era

The text discusses how propaganda has been used throughout history, dating back to ancient times, up to the present era.

Negotiating with the Chinese Communists: The United States Experience, 1953-1967

The message provides a summary of the negotiation process with the Chinese Communists between 1953 and 1967, focusing on the United States' experience.

The Law of Nations or Principles of the Law of Nature Applied to the Conduct and Affairs of Nations and Sovereigns

The Law of Nations discusses principles of law applied to nations and sovereigns, guiding their conduct and affairs.

In Confidence: Moscow’s Ambassador to Six Cold War Presidents

The book "In Confidence: Moscow's Ambassador to Six Cold War Presidents" gives an inside look at diplomatic relations during the Cold War by sharing the experiences of Moscow's ambassador to the United States.

The post-modern state and the world order

1989 marked a break in European history. What happened in 1989 went beyond the events of 1789, 1815 or 1919. These dates, like 1989, stand for revolutions, the break-up of empires and the re-ordering of spheres of influence. But these changes took place within the established framework of the balance of power and the sovereign independent state. 1989 was different. In addition to the dramatic changes of that year – the revolutions and the re-ordering of alliances – it marked an underlying change in the European state system itself. To put it crudely, what happened in 1989 was not jus...

Diplomacy and Secret Service

Intelligence officers working under diplomatic protection are rarely out of the news for long, and the last two years have been no exception. How did the relationship between diplomacy and secret intelligence come about? What was the impact on it of the bureaucratization of secret intelligence that began in the late nineteenth century? Is diplomatic immunity the only reason why intelligence officers still cluster in embassies and consulates today? What do their diplomatic landlords think about their secret tenants and how do the spooks repay the ambassadors for their lodgings? These are among ...

US Public Diplomacy: A Cold War Success Story?

The post-'9/11' revival of interest in US public diplomacy encompasses a wide variety of opinions, all overwhelmingly critical.

An English Consul in Turkey: Paul Rycaut at Smyrna, 1667-1678

The text discusses the experiences of Paul Rycaut as an English Consul in Smyrna, Turkey, from 1667 to 1678. Rycaut successfully navigated the complex diplomatic and commercial landscape of the Ottoman Empire during his tenure, maintaining good relations with local authorities and overseeing trade agreements. His role as a mediator between European powers and the Ottomans was crucial in ensuring stability and cooperation in the region during this period.

A Diplomat in Japan

The first portion of this book was written at intervals between 1885 and 1887, during my tenure of the post of Her Majesty's minister at Bangkok. I had but recently left Japan after a residence extending, with two seasons of home leave, from September 1862 to the last days of December 1882, and my recollection of what had occurred during any part of those twenty years was still quite fresh. A diary kept almost uninterruptedly from the day I quitted home in November 1861 constituted the foundation, while my memory enabled me to supply additional details. It had never been my purpose to...

A History of the United Nations. Volume I: The Years of Western Domination 1945-1955

The United Nations was formed in 1945 with a focus on maintaining world peace and promoting cooperation among nations. Initially dominated by Western powers, the organization's structure and policies evolved over the years to address global challenges and represent a more diverse membership.

Regionalism in the Post-Cold War World

Regionalism in the Post-Cold War World emphasizes the shift towards regional cooperation and integration following the end of the Cold War. It discusses how national interests can align with regional cooperation and highlights the importance of regional organizations in addressing common challenges such as security, economic development, and environmental issues. Overall, it examines the evolving nature of regionalism in the contemporary global landscape.

The Parliament of Man: The Past, Present and Future of the United Nations

The United Nations, established in 1945, aims to promote peace, security, and cooperation among countries worldwide. It provides a platform for global dialogue and decision-making on various issues, striving to uphold human rights and international law. While facing challenges and limitations, the UN continues to play a crucial role in addressing global challenges and advocating for a more peaceful and sustainable world.

International Diplomacy Volume I: Diplomatic Institutions

The message provides information related to international diplomacy found in "International Diplomacy Volume I: Diplomatic Institutions.

Ellsworth Bunker: Global Troubleshooter, Vietnam Hawk

The message focuses on the life and career of Ellsworth Bunker, depicting him as a global troubleshooter and a Vietnam Hawk.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: Comet of the Enlightenment

The text discusses Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's influential role in the Enlightenment period, emphasizing her advocacy for inoculation against smallpox. Her writings and personal experiences helped spread the practice across Europe and challenge prevailing medical beliefs.

Byzantium and Venice: A study in diplomatic and cultural relations

This book traces the diplomatic, cultural and commercial links between Constantinople and Venice from the foundation of the Venetian republic to the fall of the Byzantine Empire. It aims to show how, especially after the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Venetians came to dominate first the Genoese and thereafter the whole Byzantine economy. At the same time the author points to those important cultural and, above all, political reasons why the relationship between the two states was always inherently unstable.

Diplomatic Classics: Selected texts from Commynes to Vattel

The message will focus on highlighting the importance of classic diplomatic texts from Commynes to Vattel in understanding diplomatic history and principles, fostering a deeper comprehension of international relations.

The Long Affair: Thomas Jefferson and the French Revolution

Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence (1776) and third president of the United States (1801-9), was one of the warmest and most influential American supporters of the French revolution. He had also been a diplomat. In fact, he had joined the American mission in France in 1784, and replaced Benjamin Franklin as minister in the following year. He witnessed the outbreak of the revolution in 1789 and was then appointed secretary of state by George Washington. This scintillating book by Conor Cruise O'Brien, himself a former diplomat, analyses the blossoming and slow - very sl...

Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities

The text discusses the distinctions between privileges, immunities, and facilities in the context of diplomatic relations. It explains how privileges exempt diplomats from certain laws, while immunities protect them from legal processes in the receiving state. Diplomatic facilities are provided to aid in the duties of diplomatic missions. The history of diplomatic privileges and immunities is traced from ancient times to modern diplomacy, highlighting the role these concepts play in international relations. The text also touches on the evolution of diplomatic practices, from the Renaissance to...

The latest from Diplo and GIP

Tailor your subscription to your interests, from updates on the dynamic world of digital diplomacy to the latest trends in AI.

Subscribe to more Diplo and Geneva Internet Platform newsletters!

Diplo: Effective and inclusive diplomacy

Diplo is a non-profit foundation established by the governments of Malta and Switzerland. Diplo works to increase the role of small and developing states, and to improve global governance and international policy development.