[WebDebate #9 summary] Science diplomacy: approaches and skills for diplomats and scientists to work together effectively

Author: Ana Andrijevic

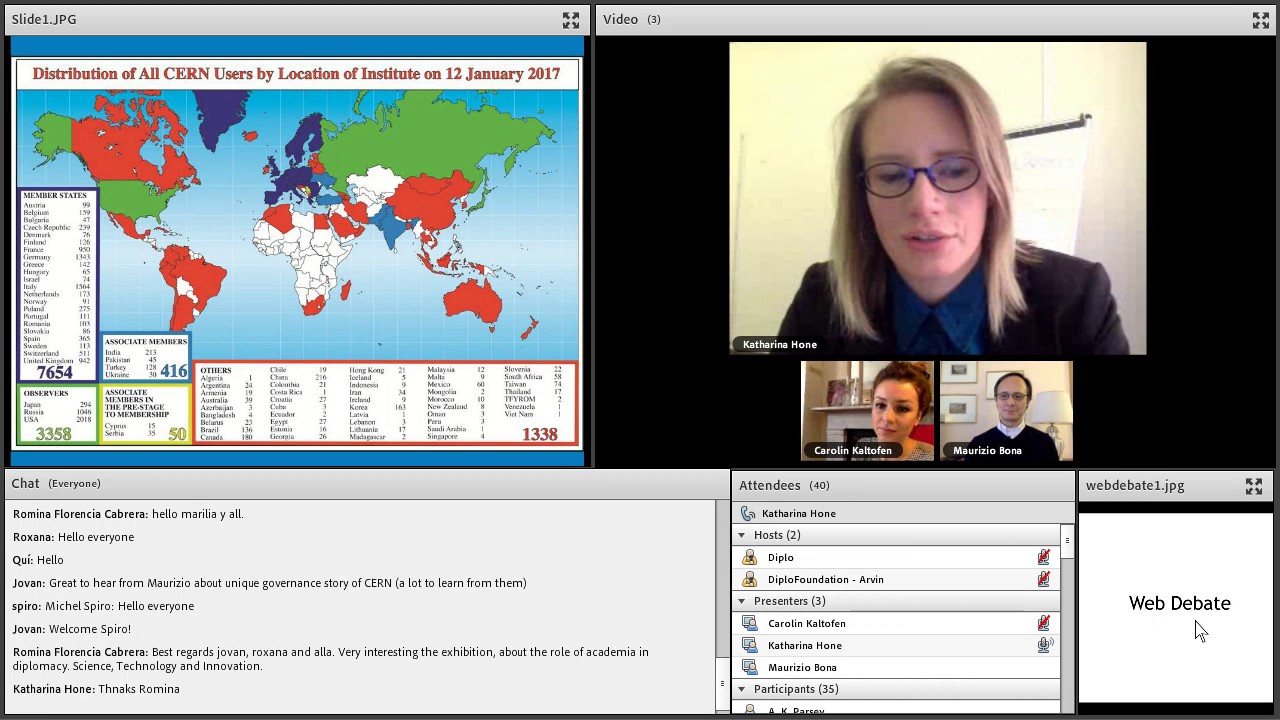

The WebDebate on ‘Science diplomacy: approaches and skills for diplomats and scientists to work together effectively’ was organised by DiploFoundation within the framework of the International Forum on Diplomatic Training (IFDT) and moderated by Dr Katharina Höne, Project Manager and Researcher Online Learning at DiploFoundation. The first speaker was Dr Maurizio Bona, Senior Advisor for Relations with Parliaments and Science for Policy and Senior Advisor on Knowledge Transfer at CERN. He gave an overview CERN’s actions in international relations, and in particular in a multilateral context. In his opinion, CERN is a good example considering its position as an international scientific institution and also as an intergovernmental organisation with 22 member states. He stressed the importance of CERN as a major stakeholder in technology developments and as such, an important stakeholder for the development of society and education across the world.

Regarding the position of CERN, he underlined the importance of dialogue, which is, as he noted, an intrinsic element of science. He noted that science has its own universal language which facilitates dialogue. Diplomats have been essential since the creation of CERN from the ashes of the Second World War in helping scientists develop international relations with other institutions. Bona also stressed the importance of improving collaboration between diplomats and scientists. From the scientific side, he noted that scientists have not been as communicative as they should be and this requires some more effort on their part. On the other hand, he added that diplomats should try to get to know the scientific world better in order to maintain an openness in discussions and build strong collaborations. Finally, he summarised his speech in three points: first, science has a key role to play in dialogue and peace; secondly, while science and diplomacy seem to be worlds apart, they can both contribute to improved dialogue and collaboration; thirdly, scientists and diplomats should take further steps towards each other.

The second speaker was Dr Carolin Kaltofen, Research Associate in Science Diplomacy at the Department of Science, Technology, Engineering and Public Policy at University College London. She said that science diplomacy has become quite a popular term in recent years, although the connection between science and diplomacy is not new. She stressed several reasons for the increasing importance of science diplomacy including the fact that there are more opportunities to engage in professional international or cross-border research, facilitated by increasing national and international prosperity. Further, security and development depend increasingly on technology. In Kaltofen’s opinion, most of today’s challenges require global collaboration. She highlighted the three dimensions of science diplomacy. The first concerns science in diplomacy, whereby science is seen as a tool to inform foreign policy objectives with scientific advice. The second relates to diplomacy for science to facilitate international science cooperation, which involves the participation of international stakeholders to develop large-scale projects with larger infrastructure in cases where costs and risks go beyond any one country’s abilities. The third involves science for diplomacy and describes the use of science cooperation to improve international relations between countries. She ended her remarks with key points on the possibility of teaching science diplomacy, but insisted that any kind of training on science diplomacy has to be context specific. She added that there is a lack of awareness of what diplomacy really needs; cautioned that efforts should go beyond a focus on states and include non-state actors; and argued that a lot more engagement with practitioners, such as CERN’s science community, is needed in order to gauge what types of training are need.

The discussion was followed by a Q&A on the contribution of CERN to peaceful relations among states. Bona underlined the importance of CERN’s neutrality and highlighted that CERN has respected this principle since its creation after the Second World War despite the complex political situation between Western countries and the Soviet Union. He insisted on the fact that all scientists, no matter their country of origin, were invited to contribute to the work done at CERN and that, therefore, there was no possibility for states to take advantage of CERN’s work for political reasons.

The question of trust was also raised during the discussion and Bona stressed that CERN’s policy was strictly apolitical. He added that the promotion of dialogue is a natural outcome of scientific collaboration because it is inclusive, thrives on transparency, and demands effectiveness and evaluation by scientific peers. Regarding transparency, he insisted that everything which is done at CERN has always been published and available as widely as possible to the public.

Further reading

- AAAS and The Royal Society (2010) New frontiers in science diplomacy

- P. A. Berkman et al. (2009) Science Diplomacy. Antarctica, Science, and the Governance of International Spaces

- D. Copeland (2011) Science Diplomacy: what’s it all about

- N. Fedoroff (2010) Science Diplomacy in the 21st Century

- E. Hollander (2015) How does science diplomacy cope with the challenges facing diplomacy more broadly?

- R. Saner (2015) Science Diplomacy to support global implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- https://www.sciencediplomacy.org/

- https://home.cern/

- https://www.ucl.ac.uk/steapp

Ana Andrijevic works as a legal junior associate at Diplofoundation and focuses her work on the Geneva Internet Plaform. She holds a Master degree in International and European Law from the University of Geneva.