It was gratifying that such a banal theme seemed to resonate with so many, to the point we had over 100 registered for the Webinar. My thanks to all of you. And my apologies if I did not respond to all the points made. In the following, please find my summary and comments on the discussion held on 30 Jan 2015. The recording of the whole discussion can be found here.

I have studied the operation of foreign ministries and diplomatic systems since 1999, but my interest in this subject was sparked by a three-day seminar I attended at Clarens, Switzerland, way back in 1967. I remain a student, still learning and gathering information, so I am open to correction and new ideas.

Can we start a blog discussion on the themes that flow from our discussion? This summary is intended to spark further conversation.

A. Let me first offer a few general observations.

- Many in different diplomatic services want to know what happens in other countries. Of course, ideas and experiences of others cannot be easily transplanted from one place to another. Some are rooted in specific traditions and context. We also have our own ‘legacy systems’, and rules that apply in the entire home civil service that cannot be easily altered. But even with these caveats, it is useful to know what happens elsewhere.

- Human resource (HR) management in any diplomatic service is one of the most important tasks; people are virtually the only real resource of the MFA. But does this receive the attention it deserves from the top management?

- Promotions connect with many other issues: recruitment, training (at entry and throughout the career), annual assessments, grievance redress, fair treatment, gender treatment, retirement processes, post-retirement activity, and others. HR is a vast and complex subject.

- Besides the executive branch, foreign ministries also employ support staff, and specialists as well. Their promotion and welfare are important, including avenues for support staff to rise to the executive branch (for instance, in India some 20% of positions in the executive ‘A Branch’ are reserved for those promoted from the ‘B’ or support branch.

- When high selectivity or ‘merit’ is applied, methods to handle those not promoted, in terms of their morale and future career, also have to be considered.

B. Rather than summarize our extensive discussion, let me highlight points that struck me, and leave it to you to add to this your observations on other issues that should also be considered. A couple of comments that came in via email are also covered.

- MFA coordination on management issues in the West: Yes, as Jovan pointed out, EU members have a mechanism for regular discussion among those that handle MFA and diplomatic service management. In addition, a group of some 15 Western countries set up by Canada about a decade back holds annual meetings of HR directors. No other regional group or cluster meets in this fashion.

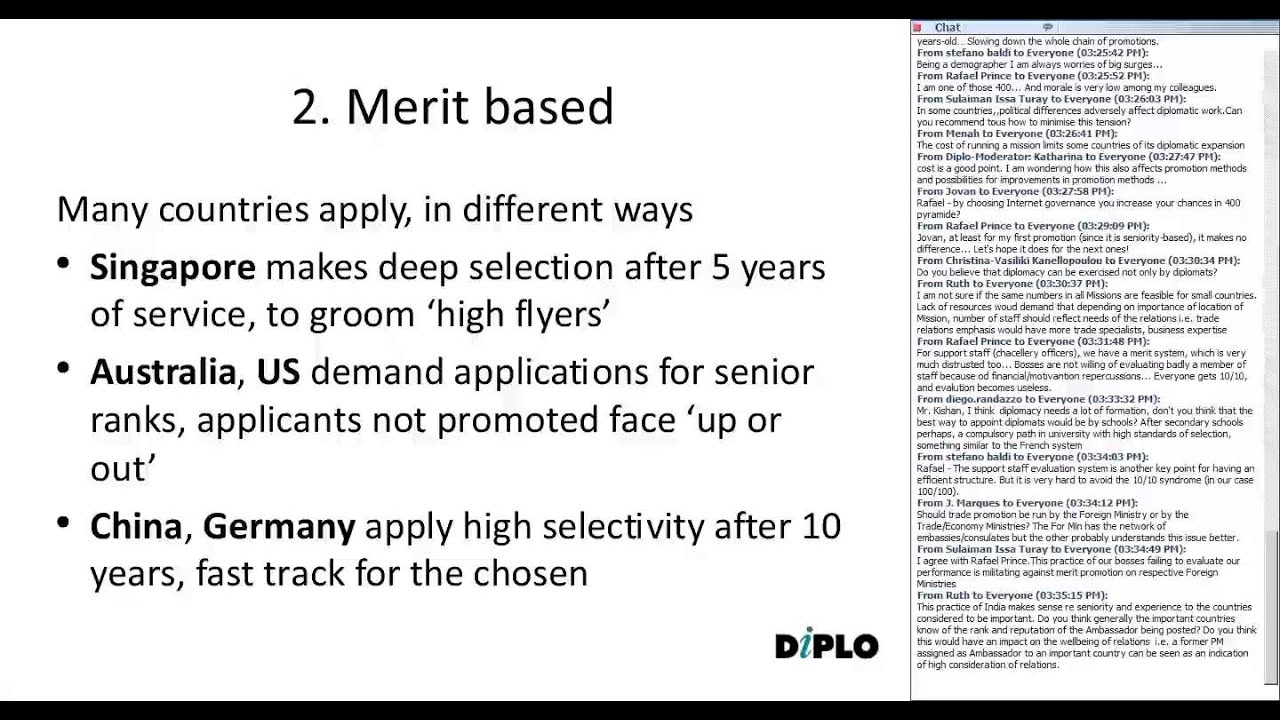

- Assessing merit: This is at the heart of HR management. Annual reports are one device, but as several noted, line managers are often unwilling to make harsh judgments, and most may give 10/10 to everyone, or give an ‘outstanding’ grading. Exams? They can be more objective, but may not capture the range of skillsets that diplomacy involves. Another method (as in Singapore) is to use a review board composed of several senior officials that take into account annual reports, reputation, and impressions gathered from diverse sources. But it would work only if the process is perceived as credible.

- Can management practices really be ‘exported’ across cultures? Each country or system has its ‘legacy’ culture and practices, which has to be taken into account if borrowed ideas are brought in. Without a ‘buy-in’, this cannot work. That is where the UK method of reform carried out by the FCO in 1999/2000 was outstanding; it relied upon teams of young officials, gently mentored but not ‘run’ by a few seniors came up with path-breaking reform ideas. [See: The New Mandarins, John Dickie (2004), the first two chapters are key.] The German Foreign Office used a like method in 2002.

- Academic qualifications: For entry into the diplomatic service, a few countries seek Master’s level degrees, while most seem to require only Bachelor level qualifications. In general, better academic qualifications should help one’s career. Do higher-level degrees, say a PhD, add to a diplomat’s capabilities? Evidence seems unclear. It may be more relevant to consider the subject of specialization, and its relevance to the work in hand, be it environment or international finance or something else. The Latin American practice of requiring ambassadors-to-be to write PhD-type thesis papers seems paradoxical.

- Would professional HR management help foreign ministries? If personnel affairs are marked by favoritism, or other malpractices, one may wish for professionals to sort out the problems. But the key issue is to end the malpractices, and diplomatic personnel that have the authority to act in a dispassionate fashion can do this. It also helps to establish norms, say for the length of tenure at posts, and ‘rotation’ between hard, moderate and soft assignments. Example: India now gives generous allowances to those that serve at tough assignments (say Afghanistan and Iraq); it has no problem in finding volunteers for these places. It is unprofessional to permit officials to stay at some places for long periods.

- Research on MFA practices: This is a major gap. No one has attempted objective assessment of ‘political’ vs. ‘career’ ambassadors, even in respect of the USA where around 30% of appointments are made from outside career ranks. Other HR practices also need objective study. This also applies to the application of methods borrowed from the corporate world, including balanced score cards (BSCs) and key performance indicators (KPIs). The UK has shown in recent years some weariness with ‘managerialist’ ways. These are fit subjects for dissertations by those who study MFAs, including perhaps diplomats on sabbaticals.

- Balanced career pyramids in diplomatic services: This is a good goal, even if it is hard to practice, when manpower needs change. At the apex, if ambassador appointments are given in large measure to those from outside the career track, a large bulge develops. Budget constraints may also block an adequate number of senior posts, which also produces distortions. Elsewhere, shortages may develop at junior levels and a bulge in middle ranks.

- Dangers of outsourcing: Brian Barder’s What Diplomats Do gives examples of mis-directed outsourcing. Germany had a like experience when they hired a top management consultancy company to advise the Foreign Office; they came up with a ‘costing’ approach (of the kind used by lawyers, consultants and others who tally the hours devoted to different tasks) that turned out to be useless in diplomatic work, and even for consular work.

- How many missions should a small country have and of what size: Numbers will depend on specific circumstance. For example, Namibia gained independence in 1991, thanks in part to international efforts; it keeps a few missions in places where it feels it received special support. As for size of missions, I have an impression – subjective, and perhaps inaccurate – that some small countries tend to have larger missions than warranted. With a sharpening budget crunch that is almost inevitable in most countries, is it likely that more countries may opt for very small missions, and even ‘non-resident ambassadors’? (The latter are based at home and travel to the assignment country from time to time, rather different from concurrently accredited envoys.)

- Who should handle trade promotion, the MFA or the Trade/Commerce Ministry? In India we strongly opt for the MEA as the key driver, even though our 70-odd ‘commercial wings’ in embassies are funded by our Commerce Ministry. Most staff are from MEA (though we have recently agreed to take some from Commerce and elsewhere too). 25-odd countries have combined foreign and trade ministries, including Australia, Canada, the Scandinavian countries, and South Korea. You may like to see Economic Diplomacy: India’s Experience – about 25% of the book is available for free download:

- What languages should be studied? The choices will depend on the region, priorities and size of the diplomatic service, but it seems to me that small countries too have much to gain through a realistic foreign language study plan, rather than view this as simply unaffordable. Equally, high-grade English competence is a sine qua non for this profession, and not just for multilateral work.

- Competencies for a diplomat: I think Harold Nicolson gave the best set of needed qualities; I do not recall the full text but it has the words: of course I have taken these other qualities for granted (or something to that effect). My list of skills: advocacy, communication plus persuasion, credibility, likability, interest in others, people management, teamwork.

C. Here are some suggested readings:

- House of Commons, Foreign Affairs Committee, The Role of the FCO in Government, 7th Report of Session 2010-12, Vol.1 [this is available on the internet].

- Paschke Report, German Foreign Office, 2000 [https://grberridge.diplomacy.edu/paschke-report/].

- Review of the Dickie book (The New Mandarins: The Making of British Foreign Policy, John Dickie, IB Tauris, London, 2004), Business Standard, 2005.

- Lowy Institute, Australia’s Diplomatic Deficit: Reinvesting in our instruments of international policy, March 2009 [https://www.voltairenet.org/IMG/pdf/Australia_Diplomatic_Deficit.pdf].

- Rana, Kishan S, Chatterjee, Bipul, eds. Economic Diplomacy: India’s Experience, CUTS, Jaipur, 2011, [https://www.cuts-international.org/Book_Economic-Diplomacy.htm].

I much look forward to further dialogue on this subject.

Kishan S Rana

Recoding of webinar: