A blog post from the perspective of a small state

In only one month, drastic changes happened in the daily lives of the people of Trinidad and Tobago. As the global spreading of COVID-19 became more apparent, small Caribbean states like Trinidad and Tobago switched from an observational interest of what was happening on the other side of the world, to awaiting when the inevitable spread will reach their shores. Of particular concern for Trinidad and Tobago was the expected influx of visitors to the twin island state for Carnival 2020. Although the deluge of cases feared didn’t occur at that time, it was never far from our thoughts.

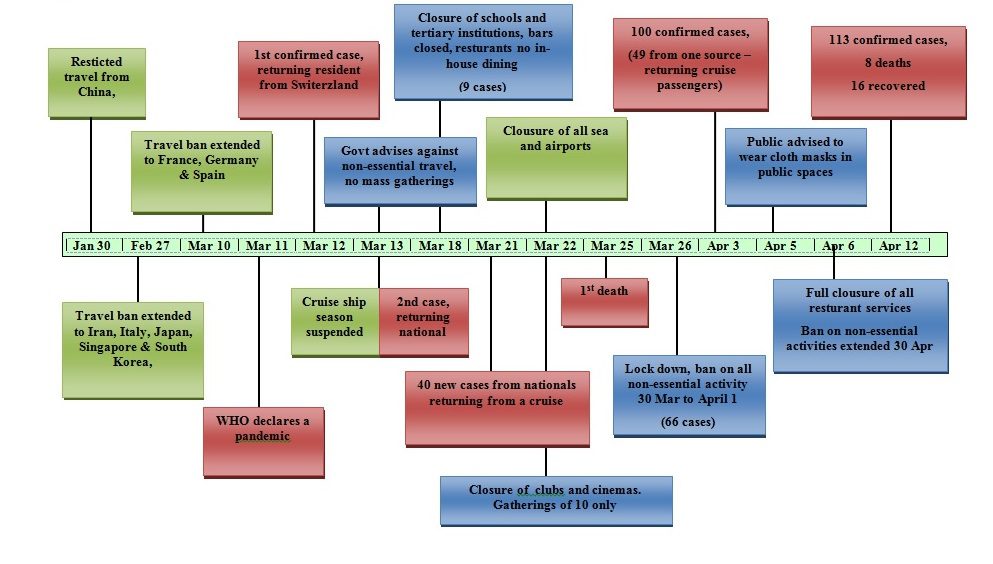

The first case was confirmed on 12 March with numbers subsequently rising to the current figures of 113 confirmed cases and 8 deaths. Initially, all cases were imported. Those returning from holiday, overseas education, and business trips, either came directly to Trinidad and Tobago or were in transit to the rest of the region. This is how the primary contact cases began. Despite government advice to restrict travel, Trinidad’s largest increase in confirmed cases to date was on 21 March and included 40 persons who went on a cruise and returned to Trinidad.

The very nature of a globally interconnected and globalised system which facilitates our economic development, and includes the mobility of persons, brought to our shores an invisible threat that quickly made its presence known. In response, the government took measured approaches to curtail spreading of the virus which has escalated in severity over the past month: from travel bans by country to complete border closure; from social distancing and social gathering limitations to stay-at-home measures and lockdown.

Managing the situation: Social responsibility and irresponsibility

As a small state, with inherent vulnerabilities linked to our geographical and socio-economic traits, safeguarding against internal and external threats is necessary. The COVID-19 pandemic will certainly intensify threats to the country and require concerted action.

In an attempt to manage the disease and limit potential spreading of the virus, which would certainly overwhelm our health system, the government indicated its resolve to take the protection of the population seriously through travel restrictions imposed on January 30 on travellers from China. These travel restrictions were extended within the Caribbean on February 27 to include Italy, Iran, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, and on March 12 to include France, Germany, and Spain as the number of patients in these countries rose. The cruise ship season was brought to a premature halt with the closing of the country’s sea ports for all cruise ships, while citizens were advised to cease all non-essential travel.

As Trinidad and Tobago began experiencing more cases and potential exposure to confirmed cases grew, schools and tertiary education facilities were closed, so were bars, restaurants suspended in-house dining, and citizens were encouraged to work from home if possible. Continuous government calls for citizens of Trinidad and Tobago to limit their activities and self-isolate for two weeks when returning from abroad have been met with diverse results. Consequently, the government moved to more stringent policies to restrict potential spreading of the virus.

Borders were completely closed to all persons, including nationals. Exceptions were provided for sea and air transportation to facilitate trade and ensure a sustainable supply of food and goods, including pharmaceutical and medical goods required for protecting the population. Public gatherings were restricted to 10 persons, which later became 5, and was finally followed by a stay-at-home order and a national lockdown with people being allowed only essential activities. Only essential services stayed open. Initially set to last from 30 March to 15 April, these restrictions have been extended to 30 April.

These difficult decisions have also brought numerous social and economic challenges similar to those experienced worldwide. Instead of protecting the broader population, border closures led to an influx of approximately 19 000 nationals, with many left stranded overseas. The closing of many businesses has impacted the economy and threatens economic security of many who have lost their jobs or are experiencing reduced incomes. Stay-at-home restrictions and the fear of contagion have raised concerns regarding damage to mental health and an increase in domestic violence. Policies have been put into place to assist these concerns.

Calls for more effort to be put into food security have risen after reports of farmers dumping produce. With an already high food importation bill, arranging assistance for crop harvesting and delivery to consumers is now essential. While this may not yet be a significant issue, it is advisable that such policies are included in efforts to secure sustainable supplies.

With schools closed for approximately a month now, there are increased concerns for the ability of schools to reopen. While some schools are fortunate enough to have the infrastructure, devices, and trained staff to effectively engage in online teaching and learning, a significant number of schools do not. While there is diverse ability among schools already engaged in online teaching, the greatest concerns are schools with no online learning. The Ministry of Education indicated that 60 000 students do not have the resources to access online learning. Secondary school admittance exams were postponed, as were secondary school leaving exams and university entry qualifications. All these issues have to be resolved before the new academic year.

The health sector

To minimise the impact on health sector resources, Trinidad and Tobago designated separate medical facilities to manage COVID-19 patients, creating a parallel health system to avoid spreading the virus within the health sector. Confirmed and potential cases are under quarantine in such facilities, while regular medical services are within the regular health system.

Accessing critical medical supplies like test kits, personal protection equipment (PPE), ventilators, and pharmaceuticals is still the primary goal of the government. Initial shutdowns in China and India, and disruptions in supply chains for such supplies, were mitigated through other sources until these supplies resumed. Securing PPE was deemed paramount, with estimates that over 1000 pieces of PPE are required to treat one COVID-19 patient during his or her contagion. Since most PPE is imported, arrangements were made to source such items worldwide.

Donations of test kits and temperature monitors from China and the EU delegation have been well received. Although the government has indicated that the US Defence Production Act has not yet presented a challenge to the country due to other available sources, the recent seizure in the USA of ventilators destined for Barbados highlights potential obstacles for supplying small states. Local manufacturing of PPE for medical personnel (via innovations like 3-D printed face shields), the production of cloth face masks for the general public, and new guidelines on using masks in public, illustrate the commitment to protecting citizens.

Coronavirus tests were initially restricted to those displaying symptoms in an effort to manage test supplies. With supply increase, the government began a new phase of broader testing which included those with flu-like symptoms. This widened the net, enabling us get a clearer picture of the situation within the broader community, but still ensured that adequate resources are maintained.

Trinidad’s COVID-19 timeline

Economic effects: Internal and external shocks

Even though the priorities are protecting the population, mitigating the spreading of the virus, and avoiding pressuring health care systems, another important concern is the impact COVID-19 is having on the economy, something small states share with their larger global counterparts. Still, small states may not be resilient as larger states, given their resources.

Even before the crisis, Trinidad and Tobago were experiencing an economic downturn from the external collapse of commodity prices of their main revenue sources (natural gas and oil) as tensions between Russia and Saudi Arabia contributed to a fall in prices.

Coupled with COVID-19 travel restrictions, a sharp global decrease in flights and a reduction of factory operations in first China and then other countries, have reduced industry energy demands in areas like manufacturing which additionally affected oil and gas prices. Adjustments will be needed after the 12 April agreement with the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) Plus countries to cut production.

Trinidad will be hit hard by this event with an estimated 50% cut in prices from January to March 2020, which will lead to a projected revenue loss of TT$ 4.5 billion. Reduction in global demand for methanol has also impacted the country as the Canadian methanol company Methanex idled one of its two plants in Trinidad. This will further contribute to revenue reduction and create a knock-on effect on other aspects of the economy, creating an even grimmer outlook for the country.

A UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) update on the potential impact of the pandemic on global foreign direct investment (FDI) and global value chains, indicated to be range from -30% to -40% leading up to 2021. UNCTAD had already reported a fall of -23% in 2019 for the Caribbean.

The resultant internal economic slowdown from the closure of non-essential businesses and services places further strain on the economy of the small state. Trinidad and Tobago will also be hit by the disruption of earnings in the tourism sector as this is one of the primary sectors in Tobago.

Within the Caribbean, one of the main economic impacts of COVID-19 will be a hit to the tourism industry, with reductions in tourism and travel, as well as the cruise industry. Travel restrictions to and from the region, as well as within the region, will have an economic fallout not only in generating revenue, but also in terms of employment. The UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (UN ECLAC) noted that an extended travel ban of one to three months would, for many Caribbean countries dependent on tourism, see a contraction of 8-25% depending on the crisis duration. All of these figures expose the vulnerability of small state economies in the Caribbean.

Relief and social benefits

Financial relief packages and grants have already been put into place by many Caribbean countries, such as cash grants for laid-off workers in the tourism industry of Jamaica. For Trinidad and Tobago, relief and social benefits include upgrade financing to the hotel industry, stimulating replacements for lost jobs, pandemic leave, rental assistance for workers displaced because of COVID-19, increases in food card allowances and family assistance grants, deferral of loan instalments by banks, reduction of credit card interest, reduction of interest rates on loans, ‘skip payment’ deferrals on commercial loans, encouraging manufacturing and private sectors to preserve jobs, and the acceleration of government repayments owed to the private sector to increase liquidity. The government also indicated it will look at all sources of funding to ensure that it can support the economy, such as the government’s Heritage and Stabilization Fund, commercial international institutions, and multilateral institutions such as the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank.

In the past month, tremendous strain has been placed on the population of Trinidad and Tobago in order to improve chances of weathering the situation. There needs to be will and effort to adhere to the government guidelines that stem from the World Health Organization (WHO) and our health officials.

Yet we are not alone in this fight. COVID-19 has brought into focus existing vulnerabilities, with a significant health sector twist, which small Caribbean states generally face. It also provides an opportunity to display how governments and societies address such vulnerabilities. We need to build our resilience for the short, medium, and long term.

Going forward, we need to find answers to many questions about the disease, including immunity and reinfection, potential national and international consequences of easing mobility restrictions, possibilities of a second wave of infections, and the potential need for travel health clearances and certificates. We are getting some insights with the relaxation of restrictions and reopening of Wuhan.

Would successive waves of infection override the levelling of the curve that many states, including small states, have sought to achieve through quick social distancing policies? How long will such states, many of which are dependent on export and service revenues, be able to have shut down economies without crippling economic distress? What we do know is that it will not be business as usual in the near future. We will see what the following months will bring for sweet, sweet T&T.

Solange Cross Mike has lectured in the area of diplomacy at the Institute of International Relations, the University of the West Indies St Augustine campus on Trinidad and Tobago. Currently, she is an associate faculty member in DiploFoundation’s courses Diplomacy of Small States and Diplomatic Law: Privileges and Immunities.

![[Webinar] Effective online learning: Opportunities, limits, and lessons-learned 2 Head, Person, Face, Photo Frame, Baby, Electronics, Screen, Computer Hardware, Hardware, Monitor, Happy, Accessories, Glasses, Photography, Portrait, Smile](https://diplo-media.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/2020/04/k2jf3xatzyk-80x80.jpg)