Prévisions 2023 : 12 tendances en matière de gouvernance numérique et de diplomatie

Author: Diplo Team

Ce blog est également disponible en anglais.

Les accords de 1998 : Succès passés, pertinence actuelle et améliorations futures

2023 est une année importante pour la gouvernance de l’internet/du numérique, car nous commençons à réexaminer certains des “accords de 1998”, qui ont établi les bases du paysage actuel de la gouvernance de l’internet/du numérique. 25 ans plus tard, nous verrons quels sont les arrangements qui ont résisté à l’épreuve du temps et quels sont ceux qui doivent être modifiés pour refléter la croissance de l’internet, qui est passé de 3,6 % de la population mondiale en 1998 (147 millions d’utilisateurs d’internet) à 69 % de la population mondiale (5,4 millions d’utilisateurs d’internet) en juillet 2022.

L’année 2023 marque un quart de siècle depuis la mise en place d’une grande partie de la structure de gouvernance numérique actuelle. En 1998, l’architecture de la gouvernance de l’internet n’a été élaborée qu’en quelques mois.

En septembre 1998 :

Google et la Société pour l’attribution des noms de domaine et des numéros sur Internet (ICANN) ont vus le jour.

Des discussions ont été entamées dans le cadre du volet “sécurité de l’information” des Nations unies, qui ont abouti à la création de l’Observatoire européen des drogues et des toxicomanies. GGE et OEWG de l’ONU .

Le site de l’ Organisation mondiale du commerce (OMC) s’est placé comme un acteur à la table des négociations sur l’économie numérique, notamment avec l’adoption du moratoire sur les droits de douane sur les transmissions électroniques.

En novembre 1998 ,

La conférence de plénipotentiaires de l’Union internationale des télécommunications (UIT) à Minneapolis, aux États-Unis, a décidé d’accueillir le Sommet mondial sur la société de l’information (SMSI), initiant ainsi un processus de discussions sur la politique numérique qui est actif aujourd’hui avec le travail du Forum sur la gouvernance de l’Internet des Nations Unies (FGI) et du Forum du SMSI.

Plongez dans l’histoire de la gouvernance de l’internet/du numérique avec notre Chronologie de la coopération numérique .

Aujourd’hui, une pression croissante s’exerce pour réformer cette architecture : (a) en créant des mécanismes de prise de décision et de recommandation sur les questions de politique numérique (potentiellement par le biais d’un FGI renforcé), (b) en créant des mécanismes holistiques de gouvernance mondiale des données, (c) en préservant et en faisant progresser l’évolution vers des discussions plus inclusives sur la cybersécurité, et (d) en évitant les tendances à la fragmentation de l’économie numérique, actuellement entretenues par des lois nationales disparates ou des accords commerciaux qui n’incluent pas un grand nombre de pays en développement et de pays les moins avancés (PMA).

12 tendances de la gouvernance numérique

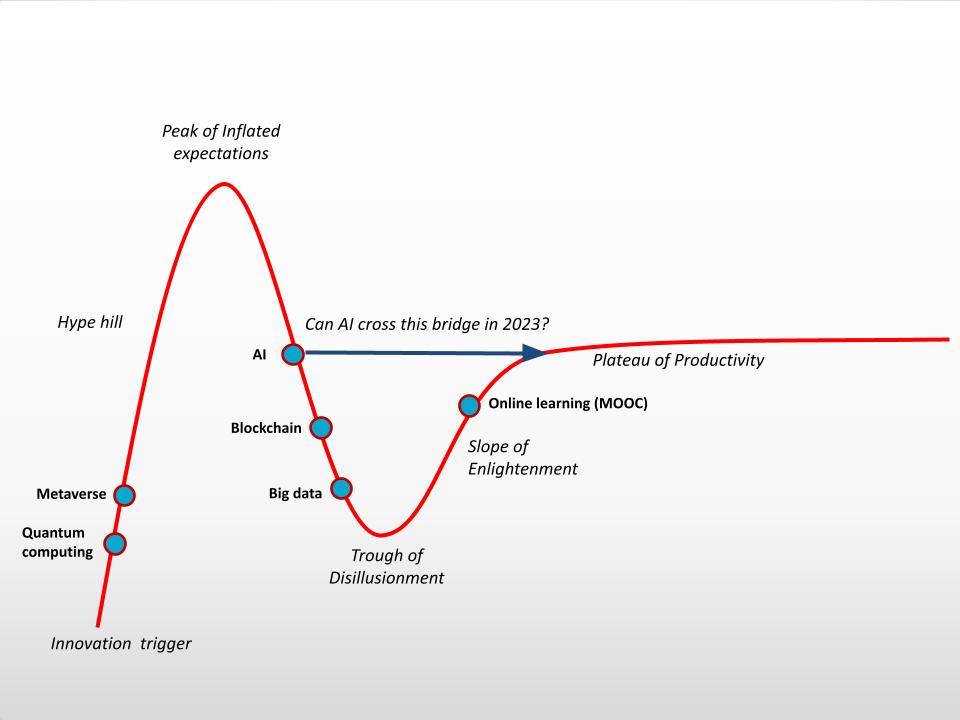

1. Les technologies : moins de publicité, plus de résultats

L’année dernière a commencé avec quelques grandes promesses. Le Web 3.0, le métavers et l’IA dans les réseaux de blockchains décentralisés nous promettaient des exploits étonnants. L’enthousiasme est retombé vers la fin de l’année (à l’exception de l’élan constant de l’IA).

Cette année a commencé sans aucune annonce concernant la prochaine grande nouveauté technologique. C’est l’occasion de prendre du recul et de voir comment nous souhaitons façonner notre avenir numérique.

Le metaverse est en tête de la liste des mots à la mode en 2022, grâce à la vision du PDG de Meta, Mark Zuckerberg, annoncée fin 2021. Progression rapide jusqu’en janvier 2023 : Le metaverse ne décolle pas comme l’envisageait Meta, anciennement Facebook, qui a centré son futur modèle économique autour de lui. L’objectif mensuel initial de 500 000 utilisateurs actifs sur Horizon Worlds – la plateforme de metaverse de Meta – a été ramené à 280 000 utilisateurs. Actuellement, il y a moins de 200 000 usagers actifs par mois. Certains des espaces virtuels d’Horizon n’ont jamais été consultés.

Pourtant, nous pensons que ce ralentissement est provisoire. Les géants que sont Microsoft, Apple et Google investissent également massivement dans les applications et outils metaverse. Une nouvelle génération d’utilisateurs ayant une expérience du jeu dominera la population Internet dans les années à venir. Sur le long terme, le metaverse ou les réalités virtuelles/étendues/augmentées sont là pour durer, et 2023 sera l’année des développements de fond et du regroupement en prévision de la future croissance du metaverse, de la réalité virtuelle et la réalité augmentée à moyen et long terme.

La Blockchain a subi une retombée négative des récents dysfonctionnements du marché des cryptomonnaies. La chute du FTX a montré comment l’architecture technique de la blockchain peut être utilisée de manière abusive pour obtenir le contraire des avantages proclamés.

Le potentiel de décentralisation de la technologie blockchain peut facilement être transformé en un contrôle centralisé par ceux qui contrôlent l’accès aux plateformes et services basés sur la blockchain. C’est ce qui s’est passé avec les plateformes technologiques, qui ont fini par dominer le marché de l’Internet malgré sa conception technique décentralisée en tant que réseau de réseaux. Il reste à voir si la même situation se produira avec la blockchain dans les années à venir.

Enfin l’ IA gagne en maturité tant au niveau de la réalisation de son potentiel que sa gouvernance. Fin 2022, Lensa et ChatGPT ont créé de nouvelles possibilités pour générer des textes et des images. En 2023, l’IA devra évoluer vers une utilisation productive, nécessitant moins de technologie et plus de changements organisationnels et de gestion pour une interaction optimale entre les humains et les machines.

En savoir plus : Metaverse | Blockchain | AI

2. La géopolitique numérique : des câbles sous-marins aux satellites

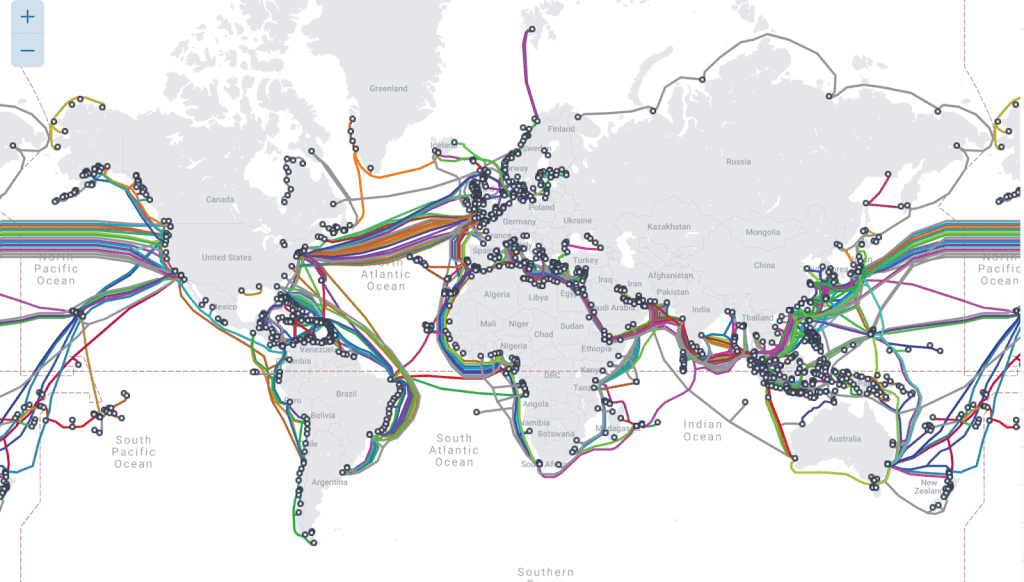

Les tensions géopolitiques numériques ne montrent aucun signe d’apaisement en 2023, notamment entre les États-Unis et la Chine. Plus inquiétant encore, les conflits et tensions mondiaux pourraient déclencher la fragmentation de l’Internet. La géopolitique numérique sera centrée sur la protection des câbles sous-marins et des satellites, la production de semi-conducteurs et la libre circulation des données.

Les tensions dans la géopolitique numérique ne montrent aucun signe d’apaisement en 2023, notamment entre les États-Unis et la Chine. Comme l’affirme The Economist “la guerre technologique entre l’Amérique et la Chine ne fait que commencer”. Le prochain défi à relever dans les relations numériques entre les deux pays sera la question du statut de TikTok aux États-Unis.

Il existe au moins trois domaines majeurs où les tensions géopolitiques se révéleront plus intenses.

(a) L’interaction entre l’interdépendance numérique et la souveraineté

La Souveraineté, qu’il s’agisse de la souveraineté numérique, des données, de l’IA ou de la cyber-souveraineté, restera en tête des priorités en 2023. Les gouvernements voudront étendre leur compétence juridique sur les activités numériques sur leur territoire et réduire les risques de retombées négatives sur la sécurité et l’économie des réseaux numériques intégrés.

La souveraineté totale sera toutefois beaucoup plus difficile à atteindre dans le monde numérique, en raison du fonctionnement d’Internet et de la puissance des entreprises technologiques.

Les approches de la souveraineté numérique varient en fonction des systèmes politiques et juridiques d’un pays. Les approches juridiques comprennent la réglementation nationale et les décisions de justice ; les approches techniques varient entre le filtrage des données et les fermetures d’Internet désapprouvées.

Le terme de souveraineté sera également utilisé plus souvent dans le contexte de l’autodétermination numérique des citoyens et des communautés, principalement liée au contrôle des données et aux futurs développements de l’IA.

L’interdépendance numérique permettra de vérifier la réalité des initiatives en faveur d’une plus grande souveraineté numérique. Elle est soutenue par une forte volonté des citoyens, des entreprises et des pays d’être connectés au-delà des frontières nationales. Elle peut même survivre aux guerres. Pendant la guerre en Ukraine, de nombreuses interdépendances entre les deux pays ont été interrompues, mais il est toujours possible d’échanger des messages entre les citoyens de Russie et d’Ukraine via l’Internet.

(b) Géopolitique des infrastructures : Câbles sous-marins, satellites, semi-conducteurs

Les câbles sous-marins sont la partie la plus vulnérable de l’infrastructure numérique mondiale. Une perturbation majeure des câbles Internet, comme cela s’est produit dans le passé, pourrait priver des pays entiers de l’Internet. Il existe plus de 500 câbles sous-marins, d’une longueur totale d’environ 1,3 million de kilomètres . Il est difficile de protéger physiquement un si grand réseau de câbles sous-marins, surtout contre les nouveaux sous-marins de haute technologie dirigés par des puissances navales. Cependant, il faut faire beaucoup plus pour assurer la protection juridique des câbles sous-marins, qui sont des infrastructures essentielles de notre société moderne.

Les satellites peuvent offrir certaines alternatives, mais ils ne peuvent pas remplacer la fibre comme réseau fédérateur mondial. Ils se sont également révélés sensibles à la géopolitique, comme le piratage de ViaSat ou la réflexion de Musk sur la poursuite de la fourniture des services Starlink à l’Ukraine. Au-delà du rôle que jouent les satellites en donnant aux gens un accès à Internet ou en leur permettant de se parler en cas d’urgence, les activités spatiales sont susceptibles d’attirer de plus en plus l’attention dans les discussions sur la gouvernance et la diplomatie dans les années à venir. Les questions liées aux interférences de fréquence, aux collisions de satellites, à la cyber-résilience et à la sécurité des services spatiaux, aux débris spatiaux, à l’exploration des ressources spatiales et à la concurrence croissante entre les nations ainsi qu’entre les acteurs privés continueront à gagner en pertinence, en s’appuyant sur les développements récents.

En 2022, nous avons vu, par exemple, une nouvelle résolution de l’UIT appelant à une coopération renforcée entre le secteur public et le secteur privé afin de garantir que “les avantages de l’espace seront accessibles à tous, partout” ; le lancement d’un groupe de travail à composition non limitée des Nations unies sur la réduction des menaces spatiales par le biais de normes, de règles et de principes de comportements responsables et un nombre croissant de pays adhérant aux accords d’Artémis (dirigés par les États-Unis, les accords définissent des principes visant à améliorer la gouvernance de l’exploration et de l’utilisation civiles de l’espace). Il est également révélateur que le Sommet du Futur de 2024, demandé par le Secrétaire général de l’ONU, devrait inclure un volet sur l’espace extra-atmosphérique, avec pour objectif de ” rechercher un accord sur l’utilisation durable et pacifique de l’espace extra-atmosphérique “.

En savoir plus : La diplomatie spatiale

Les semi-conducteurs sont au centre de la bataille géopolitique entre les États-Unis et la Chine. L’approche américaine consistant à limiter l’accès de la Chine à la production de micropuces et de technologies de pointe a commencé avec le président Trump et s’est poursuivie avec l’administration Biden. La Chine aura besoin de plusieurs années pour mettre en place la technologie nécessaire à la production de la prochaine génération de semi-conducteurs plus sophistiqués.

Ces tensions géopolitiques ont un impact en chaîne :

- Taïwan, dont la Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited (TSMC) est le principal fabricant de micropuces, est désormais au centre de la tension entre la Chine et les États-Unis.

- Les États-Unis, l’Europe et l’Inde ont commencé à construire leur propre industrie des semi-conducteurs pour éviter toute vulnérabilité future, notamment en cas de guerre à Taïwan ou de blocus économique.

- Les États-Unis investiront 280 milliards de dollars dans la recherche et la production nationales, dans le but, entre autres, de renforcer les capacités de fabrication d’Intel et d’installer des usines TSMC aux États-Unis.

- La loi sur les puces de l’UE vise à mobiliser près de 50 milliards d’euros d’investissements publics et privés dans la recherche et la production de semi-conducteurs.

- Le gouvernement et les entreprises chinoises investissent dans le domaine des semi-conducteurs afin de réduire leur dépendance vis à vis des technologies occidentales ; Les grandes entreprises technologiques chinoises, comme Alibaba, Huawei, Tencent et ZTE, rejoignent RISC-V International, un groupe qui se concentre sur les architectures de processeurs open-source.

En savoir plus : Géopolitique et semi-conducteurs

(c) Les flux de données dans la géopolitique émergente

La tendance générale est que les pays stockent davantage de données sur leur territoire, notamment des informations critiques telles que les dossiers médicaux et les identités numériques des citoyens.

De nombreux pays devront trouver un équilibre entre la souveraineté des données et l’intégration dans l’économie mondiale. Plus ils conservent de données à l’intérieur de leurs frontières nationales, moins ils peuvent bénéficier de l’économie numérique internationale et de la croissance. La libre circulation des données sera essentielle pour les petites économies et celles orientées vers l’exportation.

Le partage des données sera essentiel pour faire face aux problèmes mondiaux tels que le changement climatique. Dans le même temps, les données collectées et traitées localement peuvent conduire à de nouveaux services d’IA et de données ouvertes à l’échelle nationale ou régionale, ce qui pourrait soutenir la croissance des économies locales et réduire les bénéfices de certaines grandes entreprises technologiques.

En savoir plus : La Gouvernance des données

3. L’élan numérique de l’IBSA : lier le développement, la démocratie et la diplomatie

L’IBSA, qui signifie Inde, Brésil et Afrique du Sud, est un groupe de démocraties et d’économies en développement dotées d’une scène numérique dynamique. Ils sont de fervents partisans des approches multilatérales et multipartites, avec de nombreux exemples d’inclusion de la communauté technologique, du monde universitaire, du secteur privé, de la société civile, des communautés locales et d’autres acteurs dans la gouvernance numérique.

Ces trois pays, qui se soucient tous de développement, de démocratie et de diplomatie, peuvent-ils apporter une nouvelle énergie à la gouvernance numérique ?

L’Inde, le Brésil et l’Afrique du Sud (IBSA) – qui collaborent ensemble par le biais du Forum IBSA – sont susceptibles de jouer un rôle de premier plan dans le processus de réforme de la gouvernance numérique.

Il y a un élan autour des trois D : le trio est composé d’économies en développement, de démocraties fonctionnelles et de partisans de la diplomatie multilatérale.

Les premiers résultats tangibles de l’élan numérique de l’IBSA pourraient être attendus pendant la présidence indienne du G20, qui, entre autres, promouvra “un nouvel étalon-or pour les données“.

(a) L’IBSA et le développement

La numérisation est le moteur de la croissance des économies de l’IBSA. Parmi les trois pays, l’Inde est le leader, avec une économie numérique dynamique. Dans les trois pays, la croissance numérique future se fera en raison de leur population jeune et nombreuse et de leur dynamique économique.

Mais la numérisation tend également à exacerber les principales tensions sociétales auxquelles ces pays sont confrontés, notamment la fracture numérique et la nécessité d’une gouvernance numérique qui reflète les spécificités culturelles, politiques et économiques locales.

Les trois pays ont été le fer de lance de l’inclusion numérique en donnant la priorité à un accès abordable pour les citoyens, en soutenant la formation aux compétences numériques et en mettant en place un cadre juridique pour la croissance des petites entreprises numériques. Par exemple, le système d’identification biométrique Aadhaar de l’Inde est considéré par beaucoup comme une initiative de pointe en matière d’identité numérique, inspirant des systèmes similaires dans d’autres pays. L’Afrique du Sud est un chef de file en matière d’inclusion des femmes et des jeunes. Le Brésil travaille intensément avec d’autres groupes marginalisés, des personnes handicapées aux populations autochtones.

En ce qui concerne les données et le développement durable, la présidence indienne du G20 vise un leadership stratégique avec les initiatives pratiques suivantes : auto-évaluation de l’architecture de gouvernance des données des nations, modernisation des systèmes de données nationaux pour intégrer régulièrement la voix et les préférences des citoyens, et principes de transparence pour la gouvernance des données. Avec une population importante, les pays de l’IBSA considèrent également les données comme une ressource nationale. Les appels de la présidence indienne du G20 en faveur d’un “nouvel étalon-or pour les données” peuvent contribuer à réconcilier les questions contradictoires concernant la libre circulation des données et la souveraineté des données.

(b) L’IBSA et la démocratie

L’Inde, le Brésil et l’Afrique du Sud sont tous des démocraties actives, avec des élections régulières et des scènes de société civile fortes. En Inde, c’est une initiative de la société civile réunissant plus d’un million de signatures qui a permis de bloquer le projet Free Basics de Facebook et de préserver la neutralité du réseau. Le Brésil a été le pionnier d’un modèle national multipartite unique autour du Comité directeur de la gouvernance de l’internet (CGI.br). L’Afrique du Sud a connu des succès majeurs en matière d’inclusion des jeunes et des femmes dans les processus numériques au niveau national.

Comme d’autres pays, le trio IBSA doit également faire face aux aspects numériques de leurs problèmes sociétaux et politiques. L’Inde a eu le plus grand nombre d’interruptions de l’internet au cours des dernières années. Le Brésil a été témoin d’une utilisation abusive des plateformes de médias sociaux pendant les élections. Les femmes sud-africaines ont connu des niveaux élevés de violence en ligne.

Les problèmes numériques sont abordés et discutés dans les médias, les sphères de la société civile et les parlements en Inde, au Brésil et en Afrique du Sud.

(c) L’IBSA et la diplomatie

L’Inde, le Brésil et l’Afrique du Sud sont des partisans de la diplomatie multilatérale. En tant que membres de diverses coalitions, processus et organisations internationales, ils ont une forte capacité de rassemblement. Ils peuvent également mettre en place des partenariats régionaux et mondiaux de plus grande envergure en faisant participer des pays ayant des atouts et des problèmes numériques similaires.

L’Inde et le Brésil ont tous deux accueilli des réunions du Forum sur la gouvernance de l’Internet (IGF) des Nations unies, et tous deux soutiennent l’inclusion politique du monde universitaire, de la société civile, des entreprises et d’autres acteurs importants. Le Brésil a accueilli la réunion NetMundial de 2014, une expérience unique en matière d’élaboration de décisions multipartites.

L’Afrique du Sud a été un acteur relativement actif dans la gouvernance mondiale de l’Internet, allant d’un rôle très important dans les négociations du SMSI, à l’engagement dans plusieurs processus et discussions liés au numérique tels que l’OEWG, le Comité ad hoc sur la cybercriminalité, le travail de l’UNESCO sur la recommandation sur l’éthique et l’IA, et les débats du Conseil des droits de l’homme de l’ONU sur les droits numériques.

De nombreux pays, comme l’Indonésie et Singapour en Asie, le Mexique et l’Argentine en Amérique latine, et le Nigeria, le Kenya et le Rwanda en Afrique, partagent les préoccupations et les approches de l’IBSA en matière de gouvernance numérique.

4. La coopération numérique : mise en place du Pacte mondial pour le numérique et du “Digital 2025”.

En 2023, les processus de coopération numérique accéléreront la préparation de 2025, lorsque la mise en œuvre du Sommet mondial sur la société de l’information (SMSI) sera réexaminée, y compris l’avenir du Forum sur la gouvernance de l’Internet (FGI). En 2025, les discussions de l’ONU sur la cybersécurité évolueront de l’OEWG vers le programme d’action de l’ONU (PoA).

Les prochaines années verront également se préciser la coopération numérique autour de l’Agenda 2030, car la numérisation deviendra essentielle à la réalisation des 17 objectifs de développement durable (ODD). Une étape importante sur le chemin vers 2025 sera l’adoption du Pacte mondial du numérique (PMN) lors du Sommet du Futur des Nations unies en 2024.

L’année 2025 sera significative pour le processus du Sommet Mondial sur la Société de l’Information (SMSI). Alors que la mise en œuvre des résultats du SMSI est réexaminée, il en sera de même pour l’avenir du Forum sur la gouvernance de l’Internet (FGI).

Au début de l’année 2023, le FGI contribuera au processus du Pacte numérique mondial (PNM), en s’appuyant sur les messages du FGI 2022. Le Japon, en tant qu’hôte du prochain FGI (Kyoto, octobre 2023), est susceptible de donner une nouvelle vie à la piste d’Osaka sur la gouvernance des données, initiée pendant la présidence japonaise du G20 en 2019.

Il conviendra également de garder un œil sur les travaux du groupe de direction du FGI en 2023. Nommé en 2022, ce comité est censé contribuer à accroître la visibilité du FGI et à “fournir une contribution et des conseils stratégiques” sur le forum.

Le mandat actuel de 10 ans du FGI arrivant à son terme en 2025, nous verrons très probablement les discussions sur l’avenir du forum s’accélérer, y compris son interaction avec le travail du Bureau de l’Envoyé du Secrétaire général des Nations Unies pour la technologie.

Plongez plus profondément : Rapport de synthèse du FGI 2022

En ce qui concerne le processus du Pacte mondial pour le numérique, facilité par le Rwanda et la Suède en collaboration avec l’Envoyé du Secrétaire général de l’ONU pour la technologie, les consultations multipartites seront suivies de discussions lors d’une réunion ministérielle en septembre 2023 (consacrée à la préparation du Sommet du Futur de 2024).

Tout au long de l’année 2022, de nombreuses questions ont été soulevées au sujet du processus du PMN et du pacte lui-même :

- Comment la contribution des parties prenantes alimentera-t-elle exactement l’élaboration du pacte, étant donné qu’il s’agira en fin de compte d’un document que les États membres de l’ONU négocieront et approuveront ?

- Dans quelle mesure le pacte sera-t-il détaillé dans la description des principes de l’avenir numérique ? Et dans quelle mesure est-il réaliste d’attendre des États membres qu’ils se mettent d’accord sur un point qui n’a pas encore été énoncé auparavant ?

Au moins certaines questions devraient commencer à trouver une réponse en 2023.

En savoir plus : Le Processus PMN

5. Les droits de l’Homme en ligne : protéger ce qui fait de nous des êtres humains

Les droits de l’Homme sont à la fois permis et menacés en ligne. Ces deux extrêmes vont les définir en 2023 avec les développements spécifiques suivants : :

- Une implémentation plus profonde de la première génération de droits de l’Homme en ligne, telles que la liberté d’expression et la protection de la vie privée.

- Une protection plus large des droits de l’Homme en ligne pour la deuxième génération (droits économiques, sociaux et culturels) galvanisée autour de l’inclusion numérique et la troisième génération (droits environnementaux, intergénérationnels et culturels) .

- L’émergence d’une quatrième génération : La protection de l’intégrité humaine et du libre arbitre car ils seront affectés par les développements de l’IA et des neurosciences.sciences.

Le principal défi consistera à renforcer l’application des règles existantes en matière de droits de l’homme en ligne tout en élaborant des réglementations équilibrées pour les nouveaux domaines (par exemple, des réglementations qui encouragent les développements éthiques des neurosciences tout en protégeant la dignité et l’intégrité humaines).

En 2023, nous pouvons nous attendre à ce que les États-Unis et les pays membres de la Déclaration pour le futur de l’Internet se concentrent sur la mise en œuvre de la liberté d’expression, de la protection de la vie privée et d’autres droits de l’Homme de première génération. L’UE continuera à insister sur la protection des données et de la vie privée. En outre, l’UE s’efforcera davantage de lier les questions relatives aux droits de l’Homme à la normalisation et aux autres modes de développement de la technologie.

Une approche globale de la numérisation et des droits de l’Homme mettra sous les projecteurs la question des droits de l’Homme de deuxième génération (droits économiques, sociaux et culturels) et de troisième génération (environnementaux et intergénérationnels).

La quatrième génération des droits de l’Homme deviendra également plus pertinente, déclenchée par les risques résultant des développements de l’IA, des bio et des nanotechnologies. En septembre 2022, le Conseil des droits de l’Homme des Nations unies a adopté une résolution demandant une étude “sur l’impact, les opportunités et les défis des neurotechnologies en ce qui concerne la promotion et la protection de tous les droits de l’Homme, y compris des recommandations sur la manière dont les opportunités, les défis et les lacunes en matière de droits de l’Homme découlant des neurotechnologies pourraient être traités par le Conseil”. Le Conseil de l’Europe a également lancé un débat politique sur les neurotechnologies.

Davantage de nouveaux angles et aspects seront introduits dans le travail des organes des droits de l’Homme de l’ONU. Par exemple, l’inclusion numérique et l’accès à Internet gagneront en importance dans le contexte de la promotion et de la protection des droits des groupes marginalisés, des jeunes, des femmes et des personnes handicapées.

Comme les questions relatives aux droits de l’Homme sont de plus en plus souvent évoquées dans les discussions sur la normalisation, il y aura une volonté d’intégrer les approches des droits de l’Homme par la conception dans les normes techniques qui font partie du processus de conception et de développement de nouveaux matériels et logiciels.

En savoir plus: Les principes des droits de l’Homme

6. Contenu : l’expérience Twitter et la gouvernance de contenu

En 2023, les pays et les entreprises renforceront leur recherche de nouvelles pratiques en matière de gouvernance des contenus. Cela aura un impact sur l’économie, les droits de l’homme et le cadre social des sociétés du monde entier.

Au niveau multilatéral, l’UNESCO se concentrera sur le contenu en tant que bien public, tandis que le Conseil des droits de l’homme de l’ONU abordera le contenu par le biais de la liberté d’accès à l’information.

Dans le secteur des entreprises, le succès ou l’échec de l’expérience Twitter d’Elon Musk aura de profondes répercussions sur l’avenir de la gouvernance des contenus.

La plupart des initiatives en matière de gouvernance de contenu tenteront de trouver un équilibre entre le statut juridique des plateformes de médias sociaux et leur rôle social. Juridiquement parlant, il s’agit d’entreprises privées dont la responsabilité légale pour le contenu qu’elles publient est très faible. Socialement parlant, ces entreprises sont des services publics d’information qui ont un impact sur la perception qu’ont les gens de la société et de la politique. Le fondateur de Twitter, Jack Dorsey, a décrit Twitter comme “la zone de conversation publique de l’internet”.

Actuellement, aux États-Unis, les plateformes technologiques ne sont pas responsables du contenu qu’elles hébergent (conformément à l’article 230 de la loi américaine sur la décence des communications). Bien que des appels aient été lancés par les deux partis du Congrès américain pour revoir cet arrangement, la gouvernance du contenu aux États-Unis est toujours entre les mains des entreprises technologiques. La chose la plus importante qui se produira au cours de l’année à venir sera la façon dont l’expérience politique de Musk avec Twitter se déroule. S’il réussit, il pourrait montrer qu’un modèle d’autorégulation pour la gouvernance du contenu est possible. S’il échoue, ce sera le signe que le Congrès américain doit intervenir avec une réglementation publique, très probablement en révisant la section 230.

Dans l’UE, la gouvernance des contenus s’est déplacée vers la réglementation publique. La loi sur les services numériques (Digital Service Act, DSA) a introduit de nouvelles règles plus strictes que les entreprises de médias sociaux devront suivre. Leur mise en œuvre débutera en 2023.

À l’instar du RGPD et de la réglementation des données, de nombreux pays sont susceptibles de s’inspirer de l’approche DSA de l’UE en matière de gouvernance des contenus.

Au niveau multilatéral, l’UNESCO accueillera en février 2023 la conférence Internet for Trust : Réglementer les plateformes numériques d’information en tant que bien public, comme prochaine étape du développement de la gouvernance de contenu autour de son Guide pour la réglementation des plateformes numériques : Une approche multipartite.

Comment la gouvernance des contenus va-t-elle évoluer en 2023 ?

En 2023, les politiques de contenu continueront probablement à évoluer en fonction de l’évolution du paysage numérique. Les entreprises devront s’assurer que leurs politiques de contenu sont à jour et reflètent les dernières tendances en matière de technologie, de confidentialité et de protection des consommateurs. Les politiques de contenu doivent être conçues pour protéger les utilisateurs contre les contenus malveillants ou inappropriés, tout en leur permettant d’accéder aux informations dont ils ont besoin. Les entreprises doivent également tenir compte de la manière dont leurs politiques de contenu peuvent les aider à atteindre leurs objectifs commerciaux, tels que l’accroissement de l’engagement des clients ou l’augmentation des revenus. Les politiques de contenu doivent également être conçues pour garantir la conformité aux lois et réglementations applicables, telles que celles relatives aux droits d’auteur.

En savoir plus: Politique des contenus

7. Cybersécurité : préserver l’Internet en période de crise

Dans la mesure où nous aimerions qu’Internet soit un espace plus sûr, il existe au moins deux raisons qui entravent les efforts de chacun :

- De nouvelles vulnérabilités – résultant de notre dépendance à l’égard de technologies complexes.

- La détérioration de la géopolitique mondiale avec des retombées négatives sur l’espace numérique

La bonne nouvelle est que les pays du monde entier, notamment en Afrique et en Asie, renforcent leur protection en matière de cybersécurité. Il est également prometteur de voir les négociations des Nations unies sur la cybersécurité se poursuivre. Les risques sont importants, mais des solutions émergent.

La guerre en Ukraine, qui a occupé une grande partie de l’année 2022, a dégénéré au-delà de ses frontières. Elle a été menée à la fois sur le terrain et en ligne, principalement par le biais de cyberattaques. Les cyberrisques dont nous vous avons mis en garde au début du conflit – de l’attribution erronée de cyberattaques aux cyberdélits contre les infrastructures critiques ou les entreprises de pays tiers – restent une menace viable.

Dans ce contexte géopolitique, il y a deux raisons principales pour lesquelles il est difficile de faire d’Internet un espace plus sûr.

La première est que nous augmentons notre dépendance à la technologie plus rapidement que jamais. Par exemple, nous avons transféré tout et n’importe quoi vers le Cloud, qui autrefois semblait sûr, mais qui l’est de moins en moins (comme le confirment les attaques et les brèches dans les services Cloud de Twitter, Uber, Revolut et LastPass). Les attaquants sont devenus plus ingénieux et déterminés à percer n’importe quoi.

La seconde est que la technologie devient encore plus complexe :

- Les capteurs et l’internet des objets (IoT) sont intégrés aux systèmes industriels et à leur technologie opérationnelle.ll

- Les codes intelligents et l’intelligence artificielle sont intégrés dans tous les domaines, des applications de santé aux systèmes d’armes autonomes létaux (SAAL) comme les drones militaires.

- Les systèmes se connectent grâce aux technologies de communication naissantes comme le Li-Fi (acronyme de light fidelity), la 5G et les satellites en orbite terrestre basse (OTB).

Dans notre hâte d’innover, beaucoup de ces technologies naissantes manquent encore de normes de sécurité et de bonnes utilisations, et sont des cibles faciles.

Il y a toutefois lieu d’être optimiste. De nombreux gouvernements et institutions ont renforcé leur cyberrésilience en réponse à la menace d’attaques plus graves et plus lourdes de conséquences, telles que celles observées pendant la guerre en Ukraine. Les pays en développement s’intéressent de plus en plus à l’agenda de la cybersécurité, et leur participation accrue aux processus mondiaux pourrait faire pression sur les principales cyberpuissances pour qu’elles agissent de manière plus responsable.

Au sein du Comité ad hoc de l’ONU sur la cybercriminalité , dont l’objectif principal est de rédiger le premier projet de convention internationale sur la cybercriminalité, les pays ont fait quelques progrès sur les dispositions relatives aux différentes définitions de la cybercriminalité, aux mesures procédurales, à l’application de la loi et à l’applicabilité des dispositions internationales relatives aux droits de l’Homme. Et même si les positions divergentes sont nombreuses, l’élan général semble prometteur, et nous pourrions apprendre encore d’autres bonnes nouvelles de Vienne et de New York en 2023.

Jusqu’à présent, il y a eu trois sessions, et un document de négociation consolidé a été préparé par le président du comité avec le soutien du Secrétariat. Ce document est une compilation des propositions des États concernant les dispositions générales, la criminalisation, les mesures procédurales et l’application de la loi du projet de convention.

Un deuxième document de négociation consolidé sera préparé en 2023, sur la base des résultats de la troisième session du comité concernant la coopération internationale, l’assistance technique, les mesures préventives, le mécanisme de mise en œuvre et les dispositions finales de la convention. Fondamentalement, ces documents associés pourraient servir de point de départ aux États membres pour rédiger la convention, qui devrait être présentée à l’Assemblée générale des Nations unies (AGNU) lors de sa 78e session en septembre 2023.

L’un des principaux débats qui devrait avoir lieu avant la finalisation du projet de convention concerne la pénalisation des infractions. En bref, un groupe d’États propose que la convention se limite à la répression des crimes cybernétiques et cyberdépendants, tandis qu’un second groupe souhaite étendre la compétence de la convention à d’autres infractions, y compris le cyberterrorisme. Si ce débat débouche sur une impasse, les États pourraient soit convenir d’opter pour un champ d’application limité et laisser la place à des négociations ultérieures, soit étendre son champ d’application par le biais d’un protocole facultatif.

Un autre problème est la protection des droits de l’Homme et des libertés fondamentales. Les organisations de leur défense telles que Human Rights Watch, ont soulevé des inquiétudes quant à leur protection dans le cadre de la lutte contre la cybercriminalité, et appellent à davantage d’efforts pour assurer leur protection effective.

Le Groupe de travail à composition non limitée (GTCNL) des Nations unies sur la cybersécurité est une autre paire de manches, mais il a également bien progressé dans l’exécution de son mandat. Le GTCNL, est à mi-chemin de son mandat de cinq ans, et a un calendrier chargé en 2023, avec deux sessions de fond, des consultations plus informelles sur un répertoire de points de contact (PoC), et un autre rapport d’activité annuel.

Un autre processus sous les feux de la rampe sera le Programme d’action (PoA), un dispositif axé sur l’action, piloté par l’ONU et destiné à apporter un soutien concret à la mise en œuvre de normes cybernétiques convenues. La déclaration de la Première Commission de l’Assemblée générale des Nations Unies du 5 novembre 2022 sur le Programme d’action sur la cybersécurité a fait de l’établissement du Programme d’action une réalité. Toutefois, son champ d’application, sa structure et son contenu font l’objet de discussions qui s’intensifieront en 2023 avant 2025, date à laquelle le Programme d’action est censé démarrer après la conclusion des travaux du Groupe de travail sur la cybersécurité (2021-2025).

Consultez les dernières informations sur la situation actuelle des négociations de l’ONU sur la cybersécurité (GTCNL et PoA) .

8. L’économie numérique : commerce, fiscalité et cryptomonnaies

L’économie numérique subira de plein fouet les effets de la crise économique, avec une possible récession en 2023. Il y aura moins d’argent pour la prochaine grande innovation – quelle qu’elle soit. Comme les investisseurs optent pour des solutions économiques sûres, il est peu probable que les investissements numériques soient leur cheval de bataille.

Le bitcoin, souvent qualifié de nouvel or noir, a perdu de son attrait en raison des récents échecs des cryptomonnaies. L’élan du Web 3.0 a ralenti. L’informatique quantique est trop lointaine à ce jour pour avoir un impact économique majeur.

En terme de gouvernance de l’économie numérique, l’accent sera mis sur le commerce numérique, les flux de données, la mise en œuvre du nouvel accord fiscal mondial et la réglementation des crypto-monnaies.

Alors que la crise économique se développe dans le monde entier, l’économie numérique va en faire les frais. Les perspectives ne sont pas bonnes pour la ” future grande innovation ” – il n’y a pas assez d’argent.

Avec autant de sombres prévisions pour l’économie, la gouvernance de l’économie numérique se concentrera sur trois domaines principaux : le libre-échange, les flux de données et la mise en œuvre du nouvel accord fiscal mondial.

(a) Le commerce (libre) numérique

L’Organisation mondiale du commerce (OMC) va redoubler d’efforts dans les négociations sur le commerce électronique cette année. Voici pourquoi

En 2019, un sous-ensemble de membres de l’OMC s’est réuni pour former l’initiative de déclaration conjointe (JSI) sur le commerce électronique. Le groupe de 87 États membres travaille à l’élaboration d’un accord contraignant, couvrant à la fois les sujets commerciaux classiques, tels que l’accès au marché et la facilitation des échanges, et les questions de politique numérique, telles que les flux de données et la localisation, la confidentialité en ligne, la cybersécurité et le pourriel. De nombreux pays en développement, dont l’Inde et l’Afrique du Sud, critiquent ce processus. Mais comme les protagonistes des négociations représentent 90 % du commerce mondial, tout accord conclu dans ce cadre aura de grands effets sur la manière dont le commerce électronique est réglementé dans le monde.

Au cours des dernières années, les négociateurs de la JSI ont réussi à se mettre d’accord sur certains sujets qui pourraient être considérés comme à portée de main, notamment le spam, les signatures et l’authentification électroniques, les données gouvernementales ouvertes, la protection des consommateurs et la transparence.

Au cours du second semestre 2022, les coorganisateurs de la JSI – l’Australie, le Japon et Singapour – ont lancé un travail d’inventaire afin d’identifier les propositions qui n’ont pas recueilli suffisamment de soutien, incitant leurs auteurs à les retirer. Une nouvelle version consolidée du texte de négociation montre que des progrès doivent encore être réalisés pour rapprocher les positions sur les questions les plus controversées, telles que les flux de données, la localisation des données et la vie privée. Cette nouvelle version constitue la base des négociations de 2023.

Les membres de la JSI ont une tâche difficile à accomplir s’ils veulent produire un nouvel accord d’ici la fin de l’année. Une autre option serait de viser un “résultat par niveaux”, en obtenant un accord plus modeste sur les questions qui favorisent une plus grande convergence entre les participants tout en poursuivant les négociations sur d’autres questions en 2024 – une solution qui contrariera les pays qui ont mis l’accent sur les sujets les plus numériques dans le programme de négociation, et qui perçoivent ces questions comme la clé d’un résultat vraiment significatif.

L’importance de l’intégration des aspects de développement du commerce électronique est également claire. Toutefois, les aspects liés au développement pourraient rester insuffisamment abordés s’ils ne sont couverts que par des dispositions transversales et générales. Des engagements approfondis et systématiques dans des domaines spécifiques pourraient être une option viable.

Alors que les négociations sont toujours en suspens à l’OMC, le commerce numérique continue d’être réglementé par des accords de libre-échange et des accords sur l’économie numérique, qui se multiplient dans le monde entier. La JSI a été considérée non seulement comme une bouffée d’air frais à l’OMC, apportant potentiellement un nouveau dynamisme aux négociations, mais aussi comme un moyen de contrer une fragmentation croissante du paysage normatif du commerce numérique.

En savoir plus : Commerce électronique et commerce

(b) Mise en pratique du nouvel accord fiscal mondial

Célébré comme l’un des principaux accords négociés par l’ Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques (OCDE), l’accord fiscal mondial est confronté à une épreuve difficile : comment le mettre en application ?

L’accord fiscal, également connu sous le nom de “solution à deux piliers” (le pilier I se concentrant sur la réaffectation des bénéfices vers les pays où il y a une activité réelle, et le pilier II fixant un impôt minimum mondial de 15 %), a été soutenu par plus de 130 pays.

Les négociations sur le pilier II sont les plus avancées. Les pays du monde entier ont publié des projets de propositions et lancé des consultations publiques nationales. En décembre 2022, l’UE s’est finalement mise d’accord sur un projet de directive pour mettre en œuvre le Pilier II dans le bloc européen. Cela est intervenu après presque un an de négociations, d’abord bloquées par la Pologne, puis par la Hongrie pendant six mois. Les États-Unis ont également adopté un impôt minimum de 15 % (la loi sur la réduction de l’inflation), mais il doit encore être affiné (ou rapproché) de l’impôt minimum mondial de l’OCDE pour être pleinement conforme au Pilier II. À quoi faut-il donc s’attendre en 2023 ?

Ces négociations vont se poursuivre. Les États-Unis ont du chemin à parcourir. L’UE aussi, bien que la principale impasse semble être résolue maintenant. L’objectif ultime est que tous les pays qui ont accepté l’accord fiscal mondial de l’OCDE en 2021 aient finalement une législation en ordre. À l’exception de la poignée de pays du “no-camp”, les sociétés ne pourront se réfugier dans aucun paradis fiscal, car la plupart des pays auront un taux d’imposition minimum de 15 %.

Toutefois, les piliers étant liés entre eux, nous pouvons également nous attendre à ce que certains pays ne veuillent pas aller jusqu’au bout du pilier II avant d’avoir suffisamment travaillé sur la manière de mettre en œuvre le premier.

Les négociations sur le premier pilier avancent également. L’un des principaux défis est que les discussions techniques sont compliquées – et longues. Le pilier I exigera également que les pays abandonnent leurs taxes unilatérales. Mais si le processus prend trop de temps, surtout du côté des États-Unis (les entreprises américaines seront les plus touchées par la nouvelle règle fiscale mondiale), des pays comme le Canada continueront à menacer d’imposer de nouvelles taxes unilatérales, ou de maintenir les taxes existantes. À quoi pouvons-nous donc nous attendre ?

En 2023, des négociations élaborées se poursuivront pour définir le “montant A” du pilier I (le nouveau droit d’imposition des juridictions sur une partie des bénéfices réalisés par les multinationales) et le “montant B” (comment évaluer les activités de marketing et de distribution de base d’une entreprise). La convention multilatérale, dont la finalisation était initialement prévue pour la mi-2022, est désormais attendue pour la mi-2023. En ce qui concerne le pilier II, plus avancé, l’instrument multilatéral qui mettra en œuvre certaines parties des nouvelles règles devrait également être finalisé d’ici la mi-2023.

Entre-temps, le plus grand risque est le blocage des négociations liées au Pilier I, qui pourrait compromettre la mise en œuvre du Pilier II. Les pays pourraient également continuer à proposer de nouvelles règles fiscales unilatérales dans l’espoir d’accélèrer les négociations du premier pilier. Quelles que soient les règles unilatérales proposées, elles devront être temporaires jusqu’à la mise en œuvre des règles globales de l’OCDE.

Il y a également un débat en cours quant à l’impact sur les pays en développement : toutes ces règles, selon eux, favoriseront surtout les pays développés. Il faut donc que les pays en développement soient davantage incités à les mettre en œuvre. En outre, les règles sont trop complexes. À quoi peut-on s’attendre ? Les principaux acteurs du débat sur l’accord fiscal mondial sont les États-Unis et l’UE. Les pays en développement peuvent continuer à soulever des inquiétudes, mais ils n’ont pas assez de poids pour changer les règles. En ce qui concerne la difficulté, nous pouvons également nous attendre à ce que l’OCDE tente de simplifier leur mise en œuvre, comme elle a commencé à le faire en 2022. C’est toutefois un défi de taille – les règles fiscales sont par nature très compliquées.

En savoir plus sur : La fiscalité à l’ère numérique

(c) L’heure du bilan pour les cryptomonnaies

L’année 2022 a présenté deux facettes opposées du cycle de prospérité des cryptomonnaies. Après les valeurs record de la fin 2021, l’année 2022 a commencé par une tendance à la baisse qui s’est avérée constante tout au long de l’année.

Actuellement, le bitcoin se situe à 16 500 USD, ce qui pose problème aux créateurs de bitcoin, car ce prix est à la limite des coûts d’extraction. Cela a amené l’une des plus grandes sociétés de crypto-monnaies cotées en bourse, Core Scientific (USA), à déposer le bilan en décembre 2022.

Les fluctuations du prix du bitcoin sur une période d’un an.

L’année 2022 restera dans les mémoires comme celle des ruptures majeures pour les grands opérateurs du secteur. Cela a commencé par l’effondrement des ” monnaies stables algorithmiques ” comme Luna, s’est étendu aux plateformes de dépôt de cryptomonnaies comme Celsius, et s’est terminé par un coup de théâtre : la chute de la troisième plus grande bourse de cryptomonnaies au monde, la FTX.

La bourse FTX, dont le siège social se trouve aux Bahamas, a détourné plus de 2,5 milliards de dollars US des fonds de ses clients, les détournant vers une société affiliée, Almeda Research. Cette affaire très médiatisée a suscité l’inquiétude des régulateurs du monde entier. En 2023, les États continueront d’adopter des réglementations sur les actifs numériques, notamment, liées à la protection des consommateurs, et à l’implication claire des institutions financières qui contrôlent l’industrie.

Il s’agira certainement d’une année charnière. La question clé sera celle que The Economist a posée : La crypto peut-elle survivre à son dernier hiver ?

En savoir plus : Les crytomonnaies

9. La normalisation numérique : la gouvernance par des moyens techniques

En 2023, la pertinence des normes numériques en tant qu’approche de “gouvernance en douceur” augmentera. Les normes offrent des alternatives à la carence d’accords politiques multilatéraux.

Les normes sont également pratiques, utiles et directement applicables aux citoyens. Par exemple, en 2023, les nouveaux utilisateurs d’iPhone pourront utiliser la norme USB-C pour recharger les iPhones après qu’Apple ait dû renoncer à sa prise propriétaire suite à la pression de l’UE. En 2023, les premiers appareils domestiques construits autour des normes Matter arriveront sur le marché. Les ampoules, les thermostats et les autres objets de l’internet des objets (IoT) deviendront compatibles et plus simples à utiliser.

L’accalmie dans les développements technologiques rapides sera l’occasion de définir des normes pour la croissance technologique future de l’IA, du metaverse et de l’informatique quantique, entre autres. Et, dans la continuité des tendances des années précédentes, nous assisterons très probablement à une intensification de la coopération sur les questions de normalisation numérique entre certains pays, ainsi qu’à une interaction plus forte entre les processus de normalisation et les droits de l’Homme.

Bien que pratiquement invisibles, les normes techniques sont partout autour de nous, des protocoles qui font fonctionner Internet aux dizaines de spécifications intégrées dans nos téléphones portables. À la base, elles décrivent comment les technologies, les produits et les services sont fabriqués et comment ils fonctionnent. Elles leur permettent de fonctionner ensemble et rendent les services plus sûrs et meilleurs.

Par exemple, une avancée majeure en 2022 a été l’adoption par la Connectivity Standards Alliance de Matter, une norme permettant l’interopérabilité entre les appareils de la maison intelligente. Soutenue par les géants de la technologie Apple, Amazon, Google et Samsung, la nouvelle norme Matter devrait accroître la sécurité des appareils domestiques. Selon les mots du président et directeur général de la Connectivity Standards Alliance, Tobin Richards : “Matter place également la barre plus haut en matière de sécurité, en utilisant la blockchain pour valider et stocker les informations d’identification sur le réseau domestique, en cryptant les messages (commandes) entre les appareils, en permettant un contrôle local (pas de Cloud) et en incluant une voie vers des mises à jour de sécurité simples”.

Au-delà de leur nature technique, les normes ont également des aspects économiques, sociaux et (géo)politiques. Leur nature multiforme est devenue de plus en plus visible ces dernières années. Par exemple, elles ont été inscrites à l’ordre du jour de cadres intergouvernementaux bilatéraux et multilatéraux tels que le G7, le G20, le Quad (Australie, Inde, Japon, États-Unis) et le Conseil du commerce et de la technologie UE-États-Unis. Elles ont également été examinées dans des cadres inhabituels, tels que le Conseil des droits de l’Homme des Nations unies.

Que pouvons-nous espérer voir en 2023 ?

(a) Pertinence des normes : De plus en plus forte

Nous prévoyons que les normes et les processus de normalisation continueront à gagner en pertinence en 2023 et au-delà, en particulier dans le contexte de l’intensification de la concurrence technologique entre les nations. Les pays partageant les mêmes idées s’efforceront probablement de renforcer la coopération et la coordination sur les questions liées aux normes, en particulier lorsqu’il s’agit d’en élaborer pour les technologies émergentes et avancées. Le Conseil du commerce et de la technologie UE-États-Unis n’est qu’un exemple : sur la base des accords conclus en 2022, l’UE et les États-Unis s’efforceront d’accroître la coopération en matière de normes et de faire progresser l’élaboration de normes internationales dans des domaines tels que la science et la technologie de l’information quantique, la fabrication par ajouts, le cryptage post-quantique et les IdO.

(b) Une relation croissante avec les droits de l’Homme

Une autre tendance qui s’affirme en 2023 sera le lien entre les droits de l’Homme et les normes numériques. Pour commencer, le Haut-Commissariat aux droits de l’Homme remettra son rapport au Conseil des droits de l’Homme des Nations unies sur “la relation entre les droits de l’Homme et les processus de normalisation technique pour les technologies numériques nouvelles et émergentes”, comme demandé par le Conseil dans une résolution de juin 2021. Le rapport comprendra probablement des recommandations visant à favoriser davantage de convergences entre les droits de l’Homme et les processus de normalisation, ainsi qu’à renforcer la participation des groupes de la société civile aux travaux de normalisation. Ensuite, au sein même des organismes de normalisation (OEN), il y aura probablement de plus en plus de discussions sur les implications en matière de droits de l’Homme des normes en cours d’élaboration, par exemple, lorsqu’il s’agit d’IA, d’IoT, d’identités numériques, etc.

(c) Les normes comme outils de gouvernance de facto

Les normes sont, en général, facultatives, et leur succès dépend de la mesure dans laquelle elles sont adoptées par l’industrie. Mais parfois, il existe également des liens clairs entre les normes et les réglementations : Elles peuvent servir de base à la réglementation ou être elles-mêmes utilisées comme outils de réglementation lorsqu’elles sont rendues obligatoires par la loi. Le lien entre les normes, les réglementations et la transformation numérique globale est illustré, par exemple, par la 7e conférence sur la normalisation de la cybersécurité qui se tiendra à Bruxelles le 7 février et qui abordera la normalisation comme moyen de soutenir les lois de l’UE relatives à la cybersécurité, telles que la loi sur la cyberrésilience.

La réglementation ayant tendance à être à la traîne des progrès technologiques, les normes ont un rôle important à jouer pour garantir la qualité, la sûreté et la sécurité des technologies qui ne sont pas encore couvertes par la réglementation. De plus, comme les tensions géopolitiques actuelles sont sur le point de réduire les chances de solutions multilatérales de gouvernance numérique, les normes numériques convenues au niveau international pourraient combler ce vide en devenant des outils de gouvernance de facto.

(d) De nouvelles normes en perspective

Alors que nous nous attendons à ce que le matraquage publicitaire autour des technologies avancées/émergentes (informatique quantique, metaverse, etc.) se tasse, les processus de normalisation vont s’accélérer. Par exemple, les travaux sur diverses normes pour l’informatique et la communication quantiques progresseront au sein d’organismes tels que l’UIT, l’Organisation internationale de normalisation (ISO) et la Commission électrotechnique internationale (CEI). En ce qui concerne les activités de normalisation pour la cryptographie à sécurité quantique, ces travaux sont également menés par des OEN nationaux et régionaux tels que le National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) aux États-Unis et l’European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) dans l’UE.

Quelques initiatives de normalisation voient le jour afin d’assurer l’interopérabilité future des plateformes metaverse. La plus importante est le Metaverse Standards Forum, soutenu par de grandes entreprises technologiques. Il convient également de noter le travail de pré-normalisation sur les metaverses initié à l’UIT en décembre 2022. Un travail de pré-normalisation similaire, cette fois en relation avec les réseaux mobiles, prend de l’ampleur à l’ETSI, où un groupe de spécification industrielle a commencé à explorer les cas d’utilisation et les exigences en matière de bande de fréquences pour les communications terahertz (THz), qui est une technologie candidate pour les réseaux 6G.

En savoir plus : Les normes numériques

10. La gouvernance des données : s’éloigner d’une approche universelle

Au fur et à mesure que les discussions sur la gouvernance des données évoluent, 2023 verra le passage d’une approche unique à des conversations sur la manière de réglementer les différents types de données, telles que les données personnelles, d’entreprise, publiques, de santé, etc. En parallèle, cela nécessitera une approche globale prenant en compte les perspectives de normalisation, de sécurité, de droits de l’Homme et de droit.

Pour les gouvernements du monde entier, 2023 pourrait être une année charnière dans leur volonté de concilier deux aspects :

- La nécessité d’établir la souveraineté sur les données critiques et sensibles qui doivent être stockées physiquement sur les territoires nationaux (registres, données de santé, etc.).

- Le fait que la libre circulation des données à la périphérie des pays et des entreprises facilite le développement économique et contribue au bien public (par exemple, les données environnementales).

Les solutions mutuellement bénéfiques sont bien sûr idéales, mais de manière réaliste, les gouvernements devront faire des compromis optimaux entre les deux.

En 2023, les données occuperont une place importante dans l’agenda du développement et du commerce. L’Inde les a placé en tête de l’agenda de la présidence indienne du G20 cette année. Elles seront également un thème central des négociations plurilatérales sur le commerce électronique à l’OMC. Très probablement, le Japon – en tant que promoteur de la libre circulation des données – tentera également de les placer en tête de liste de l’ordre du jour du FGI, qui se tiendra à Kyoto, au Japon, en octobre 2023.

Sur quoi les discussions devraient-elles porter ? Il y a au moins quatre grandes questions politiques que ces forums, ainsi que d’autres instances nationales et régionales, devraient aborder.

(a) Comment élaborer et appliquer une réglementation adéquate et suffisante à des types de données spécifiques ?

Nous avons tendance à regrouper tous les types de données dans un même panier, mais en réalité, il en existe différents types – des données personnelles aux données sectorielles et ouvertes – qui nécessitent tous une approche de gouvernance des données dédiée.

En 2023, la gouvernance des données arrivera à maturité avec la prise de conscience que nous avons besoin d’autant d’approches de gouvernance qu’il y en a de types. Ainsi, la façon dont nous gouvernons les données personnelles doit être différente de la façon dont nous abordons les données scientifiques, commerciales ou communales.

Cette prise de conscience sera progressive et sera initiée dans les organisations et systèmes qui gèrent des données spécifiques (par exemple, l’Organisation mondiale de la santé pour les données de santé, l’Organisation météorologique mondiale pour les données météorologiques et climatiques, etc.)

(b) Comment aborder les questions de gouvernance des données de manière multidisciplinaire ?

En 2023, les pays, les entreprises et les organisations internationales devront résoudre la nature multidisciplinaire de la gouvernance des données de manière exhaustive. Cela nécessitera des changements organisationnels, procéduraux et pratiques afin d’aborder les niveaux suivants de la gouvernance des données :

- Au niveau technique, les données ont besoin de normes afin d’être interopérables. Ici, le travail des organismes de normalisation et des organismes techniques devient essentiel.

- Au niveau de sécurité, les données sont exposées à de nombreuses violations. La sécurité des données est au centre des activités de l’industrie technologique et des gouvernements du monde entier.

- Au niveau économique, le modèle économique de l’internet est basé sur les données. Le rôle des entreprises technologiques qui traitent les données des utilisateurs et le rôle des autorités pour garantir la protection des utilisateurs et de leurs données entrent en jeu.

- Au niveau juridique et des droits de l’Homme, la principale question concerne la protection des droits des utilisateurs, notamment le droit à la vie privée et à la protection des données, ainsi que la prévention de la surveillance de masse. Les règles étant ancrées dans des espaces géographiques, la juridiction est souvent la principale question qui se pose en cas de litige. Les tribunaux sont de plus en plus souvent devenus des créateurs de règles de facto. La société civile joue un rôle important dans la défense des droits des utilisateurs.

(c) Comment intégrer la gouvernance des données dans les domaines et pratiques politiques traditionnels ?

Les données devenant essentielles pour tous les domaines de la coopération mondiale, les organisations internationales devront intensifier l’utilisation des données dans leurs activités en 2023, qu’il s’agisse de santé, de migration ou de commerce. Le fait de s’appuyer davantage sur les données contribuera à l’élaboration de politiques davantage fondées sur des preuves.

Dans le même temps, la pertinence croissante des données rendra également la gouvernance des données plus politique. Comme cela s’est déjà produit dans le secteur de la santé, les pays devront négocier le type de données qu’ils sont prêts à partager avec les organisations internationales et la manière dont ces données seront utilisées.

(d) Comment la réglementation des données affectera probablement l’utilisation et le développement de l’IA ?

L’IA est construite sur des données, ce qui signifie que la gouvernance des données et la gouvernance de l’IA vont de paire. Les applications d’IA émergentes telles que ChatGPT déclencheront davantage de discussions sur la relation profondément ancrée entre les deux.

En savoir plus : Gouvernance des données

11. La gouvernance de l’IA : des débats sur l’éthique aux solutions pratiques de gouvernance

L’IA est entrée dans la vie quotidienne et continue de défier les systèmes existants de manière inédite et plus visible. Prenez le modèle ChatGPT récemment lancé par OpenAI : il est peut-être plaisant de jouer avec, et il est sûrement impressionnant, mais il constitue également un défi pour les systèmes éducatifs (les professeurs essayant désormais de détecter les textes écrits par l’IA au lieu des textes plagiés), et soulève de nouvelles questions sur la protection des droits de propriété intellectuelle. Dans quelle mesure sommes-nous prêts à faire face à ces problèmes et à d’autres similaires ? Comment la gouvernance existante de l’IA peut-elle relever les nouveaux défis de l’IA ?

Au fur et à mesure que l’IA devient plus répandue dans la vie quotidienne, les questions sur la façon de la gouverner deviendront plus importantes. La portée quotidienne croissante de l’IA fera également passer l’attention des discussions générales sur l’éthique (c’est-à-dire comment s’assurer que les solutions d’IA sont développées et utilisées conformément aux principes éthiques) à des questions plus pratiques comme, par exemple, l’ajustement de la pédagogie et des politiques éducatives à la possibilité que l’IA puisse rédiger les devoirs et les thèses des étudiants. On pourrait trouver des exemples similaires de changements de politique induits par l’IA dans les domaines économique, culturel, juridique et autres.

Une bonne chose est que nous n’aurons pas besoin de partir de zéro. Il existe de nombreux processus politiques et réglementaires nationaux, régionaux et mondiaux en cours.

En 2023, l’Europe maintiendra sa tradition de précurseur en matière de gouvernance numérique (pensez aux données, à la cybersécurité et à l’anti-monopole) en faisant avancer les travaux sur le projet de loi sur l’IA de l’UE et les travaux du Comité sur l’IA du Conseil de l’Europe sur un projet de convention sur l’IA et les droits de l’homme.

Au sein de l’UE, il y a de fortes probabilités que la loi sur l’IA soit adoptée au début de 2024. Tout dépendra de la rapidité avec laquelle le Parlement européen, le Conseil de l’UE et la Commission européenne parviendront à se mettre d’accord sur les points litigieux. À la suite de l’avancée des négociations, de nombreux acteurs du numérique intensifieront leur lobbying à Bruxelles, car la réglementation européenne pourrait avoir des effets en dehors de l’UE, comme le RGPD. La loi sur l’IA pourrait également créer des tensions avec les États-Unis, fervents partisans de l’autorégulation.

Au Conseil de l’Europe, le Comité sur l’IA (CAI) a commencé à discuter d’un projet de convention [le cadre] sur l’intelligence artificielle, les droits de l’Homme, la démocratie et l’État de droit. Le projet présenté lors de la dernière réunion du Comité en septembre 2022 n’est pas encore public, mais la Commission européenne – partie aux discussions – a révélé qu’il couvre des dispositions relatives à :

- ” l’objet et le champ d’application de la convention (cadre) ;

- les définitions d’un système d’IA, du cycle de vie, du fournisseur, de l’utilisateur et du “sujet IA” ;

- certains principes fondamentaux, notamment les garanties procédurales et les droits des sujets de l’IA, qui s’appliqueraient à tous les systèmes d’IA, quel que soit leur niveau de risque ;

- des mesures supplémentaires pour le secteur public ainsi que des systèmes d’IA présentant des niveaux de risque “inacceptables” et “significatifs” identifiés sur la base d’une méthodologie d’évaluation des risques et des impacts (qui sera présentée ultérieurement dans une annexe à la convention) ;

- mécanisme de suivi et de coopération entre les parties ;

- des dispositions finales, notamment la possibilité pour les États membres de l’UE d’appliquer le droit communautaire dans leurs relations mutuelles pour les questions couvertes par la convention et la possibilité pour l’Union d’adhérer à la convention”.

Le processus de rédaction et de négociation se poursuivra en 2023 avec deux réunions de la CAI : 11-13 janvier et 1-3 février.

Il y a un risque de superposition entre les deux processus, comme l’a indiqué une récente décision du Conseil de l’UE : ‘ La convention se superpose dans une large mesure à la proposition législative [sur l’IA] dans son champ d’application puisque les deux instruments visent à établir des règles applicables à la conception, au développement et à la mise en œuvre de systèmes d’IA, fournis et utilisés par des entités publiques ou privées.” Pour résoudre ce problème, la Commission a été mandatée par le Conseil pour représenter l’UE dans les négociations de la CAI sur “les questions relevant de la compétence exclusive de l’Union, afin de protéger l’intégrité du droit de l’Union et de veiller à ce que les règles du droit international et du droit de l’Union restent cohérentes”. Il reste à voir comment les deux processus parallèles évolueront et comment les chevauchements potentiels seront abordés.

Quel est le point de vue de ChatGPT sur la gouvernance de l’IA en 2023 ?

Nous avons posé la question au chatbot appelé ChatGPT, qui a été lancé en novembre 2022, et qui est présenté comme la machine conversationnelle la plus avancée au monde.

‘Il est difficile de prédire exactement à quoi ressemblera la gouvernance de l’IA en 2023, car cela dépendra d’une variété de facteurs tels que les développements technologiques, les conditions économiques et les changements politiques et sociaux’, a répondu ChatGPT.

Cependant, il est probable que la gouvernance de l’IA continuera à être un sujet de discussion et de débat entre les gouvernements, les entreprises, les universitaires et d’autres parties prenantes. Des efforts pourraient être déployés pour établir des normes mondiales ou régionales pour le développement et l’utilisation de l’IA, ainsi que des efforts pour répondre aux préoccupations concernant l’impact de l’IA sur l’emploi, la vie privée, la sécurité et d’autres questions.

ChatGPT poursuit : Il est également possible que des cadres de gouvernance de l’IA apparaissent au niveau national ou local, adaptés aux besoins et au contexte spécifiques des différents pays ou communautés.

12. L’avenir du travail : l’hybride est la nouvelle normalité

L’année 2022 nous a apporté une recrudescence de rencontres, les individus se retrouvant dans des espaces physiques et des réunions dans le monde entier. En 2023, le travail et les négociations “s’installeront” dans un format hybride, combinant des éléments d’interactions en ligne et in situ. En plus de Zoom et des réunions en ligne, de nouveaux outils de réalité virtuelle seront développés pour faciliter une interaction en ligne sans faille. L’accent sera mis sur les nouvelles routines, procédures et réglementations pour l’interaction hybride, du travail ordinaire aux négociations diplomatiques.

Le passage à un mode de fonctionnement en ligne était prévu depuis longtemps. Les entreprises avaient déjà commencé à expérimenter lentement de nouvelles pratiques de travail à domicile, peut-être une fois par mois, peut-être une fois par semaine. Les travailleurs se réjouissaient, mais les dirigeants faisaient preuve de prudence.

En 2020, la pandémie de Covid-19 a tout changé. Les lieux de travail ont été incités à passer au travail en ligne presque du jour au lendemain. Les employés se sont installés dans leur salon. Les bénéfices de Zoom sont montés en flèche.

Alors que la pandémie commençait à libérer le monde de son emprise, la manière hybride de travailler et de se réunir (un mélange de travail en face à face au bureau et en ligne à la maison) est devenue la nouvelle norme. Elle s’accompagne d’une nouvelle série de considérations politiques :

- Comment les outils de réunion en ligne traitent-ils les données personnelles des utilisateurs, en particulier des enfants, qui ont dû commencer à utiliser des salles de classe virtuelles ?

- Quels sont les risques et les effets négatifs de la surveillance des résultats (si les entreprises en ont vraiment besoin) ?

- Comment les gouvernements doivent-ils aborder le statut des travailleurs indépendants, un secteur qui a explosé pendant la pandémie en raison de la forte demande de ce service et de la flexibilité qu’il offre ?

Click to show page navigation!