In 2020, we initiate digital monitoring for a decade around 20 keywords of digital governance.

In 2022, our prediction reflects on 20 keywords and add two more: openness and interoperability. 2022 update is provided in the orange colour.

| Interdependence | Sovereignty | Governance | Diplomacy | Geopolitics | Security | Standards | Data | Human | Ethics | Identity | Trust | Content | Sustainability | Inclusion | Commons | Inequality | Taxation | Currency | Platforms | Openness | Metaverse |

Why is Digital Policy Dictionary useful?

The dictionary should bring clarity in digital governance in the 2020s. The early 2000s were years of blue-sky thinking, with tech and online developments promising an unstoppable march into a bright digital future. But by the 2010s clouds in that blue sky could not be ignored: Edward Snowden’s revelations about mass surveillance, multiple large-scale data breaches, and the subversion of political processes by online ‘fake news’ were only some of the signs of trouble. It had become clear that digital space was not simply the utopian realm of unbridled creativity that it once seemed.

Clarity will be crucial if we are to reconcile the contrasting spirits of these two decades. Learning caution from the 2010s, we must remain aware of the various economic and political interests in play in the digital realm, and of the constraints imposed by realpolitik on our efforts to mediate them. Yet it is also imperative that we retain the creativity and optimism of the 2000s, so that innovation towards a yet-unimagined technological future can continue.

The challenge, therefore, is to maintain our clarity of vision even while we move beyond simplified binaries – of pessimism/optimism or dystopian/utopian – towards a more nuanced ‘analogue’ approach to the digital world’s complex network of technological, economic, social, legal, and most importantly human priorities.

Clarity of policy is impossible without clarity of thought and language. It is with this in mind that we present our predictions this year in the form of a Dictionary of Digital Predictions for 2020 – albeit a non-alphabetical one!

The dictionary’s principal focus is not the technology itself but tech’s broader ramifications and effects. For example, its anticipation and analysis of developments in artificial intelligence (AI) in the 2020s focuses more on ethics, standards, and governance than on machine learning or other technical aspects of AI. The entries include some practical information pertaining to their subjects: the key questions to be answered, upcoming or ongoing events and initiatives, and the relevant activities of the Geneva Internet Platform (GIP) and DiploFoundation. To contextualise this year’s predicted trends, the grey boxes provide links to our review of top digital developments in 2019, and to aid in comprehension many entries are supplemented by illustrations.

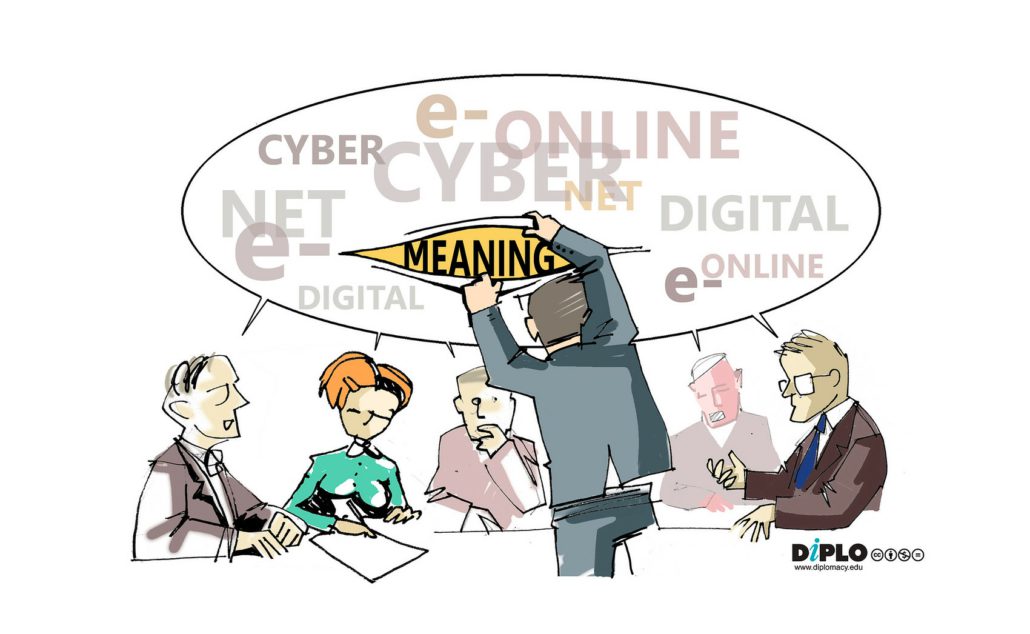

How to use and interpret prefixes?

The dictionary’s entries appear without prefixes such as digital, cyber, online, virtual, e-, or tech, and it is worth noting why. One of our intentions is to prompt reflection on the use of such prefixes, to the end of promoting clarity in our digital discussions. Some vocabulary has become established through usage and the passage of time – cybersecurity and cybercrime, e-commerce, digital trade – but other terms remain in flux: digital diplomacy, cyber diplomacy, tech diplomacy, and e-diplomacy are often used interchangeably, for instance, and multiple prefixes continue to be attached to governance, commons, geopolitics, inclusion, and many other terms. To encourage collaboration in moving towards increased semantic clarity, we invite you to respond to a Prefix Survey, which gives you the opportunity to select your preferred prefix for each of the digital terms that appear in this prediction dictionary.

We hope that the dictionary will help in the quest for shared meaning in a tech and policy space that is evolving so fast that its vocabulary and semantics can seem bewildering. Read on for 20 keywords that will be central to digital policy discussions in the 2020s:

1. Interdependence

Predictions from January 2020

Interdependence will be the defining feature of the digital 2020s. In June 2019 the Report of the UN Secretary General’s High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation (entitled ‘The Age of Digital Interdependence’) made this emphatically clear. But the role of interdependence was not always recognised. Back in 1996, John Barlow proclaimed in A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace: ‘Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.’

Behind the move from independence in 1996 to interdependence in 2020 lies the evolution of the Internet from a pioneering new technology into the critical infrastructure of twenty-first-century civilisation. Nearly all societies are now heavily reliant on the handful of tech giants that channel the lion’s share of global Internet traffic and run online platforms that operate worldwide. At the same time, those companies depend on governments to uphold the rule of law and provide stable markets, and more and more they must take into account social, cultural, and political dynamics that are specific to countries and communities across the globe. This digital interdependence is embodied physically in the Internet cables that traverse multiple national borders, and in the production chains that link data centres, companies, and consumers worldwide.

New vulnerabilities are a result of growing digital interdependence. The risks of online malignance are increasing as we become more dependent upon the weakest links in the digital network. As it isn’t given that the Internet will be a positive force for society it needs to be guided by clear rules. Negotiation, compromise, and diplomacy are the best ways to solve digital conflicts between nations.

Fast digital developments call for the ‘new Social Contract’, which should optimize digital interdependence. It should also regulate most technical and economic topics in 2020s, including data protection, cybercrime, ecommerce, and developments in AI. The four multis should be used to guide the development of a global social contract.

Multilateral diplomacy will be required to address issues raised by digital interdependence across national borders. Despite familiar claims about the Internet bringing the ‘end of geography’, echoing Francis Fukuyama’s declaration of the post-Soviet ‘end of history’, territory, borders, national sovereignty, and physical space remain of profound importance in the digital age. Our individual lives continue to be lived in geography-specific physical, legal, cultural, and socioeconomic spaces: while there are cybercrimes, we might reflect, there are no cyberjails. So although we must cultivate and benefit from the Internet’s capacity to bring us together across borders in new ways, we also need to think carefully about how we negotiate and regulate the ways in which it does so.

Multistakeholder policymaking processes will be necessary to reflect the fact that most of the digital world is run by a wide range of private and non-state actors (such as the tech firms that channel almost 90% of global Internet traffic or run the major online platforms), and those tech standards are established by a range of academic, professional, and international organisations. The effective, inclusive, and sustainable digital policy will be impossible unless all relevant stakeholders are given a place at the negotiating table.

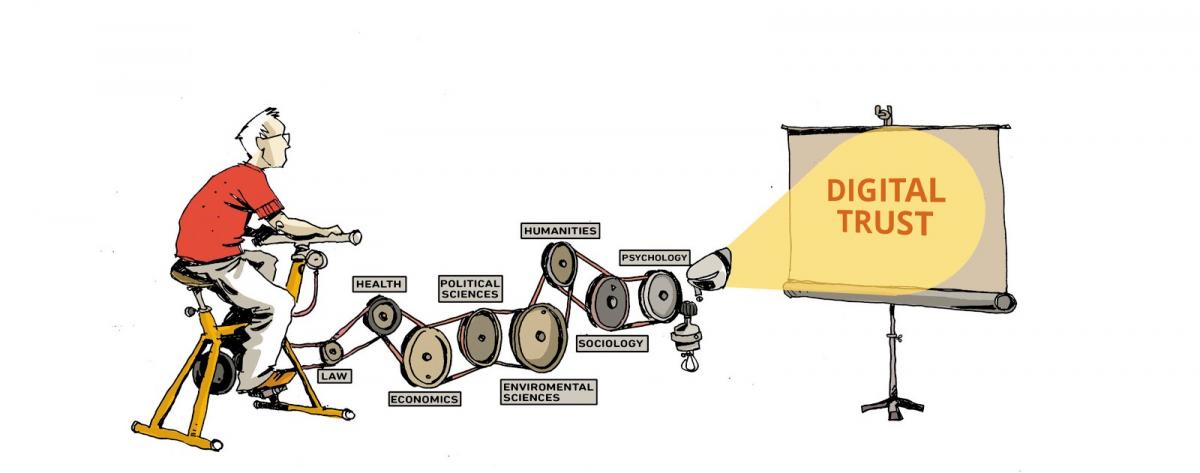

Multidisciplinary coverage will empower us to think across not only geographical borders but intellectual ones as well: technical, economic, legal, social, ethical, and more. Only by way of a ‘silo-bridging’ ethos can we meet the challenges of the tech world of the 2020s, challenges that will be less and less about technology per se and increasingly about matters of policy. This is recognised by tech giants such as Facebook and Google, which will soon have more staff in content and policy departments than in strictly technological ones. Policymakers must recognise it too, and respond with cross-silo policy approaches.

Multilevel approaches should bring digital policy issues closest to people and communities who are directly concerned with these issues. While the Internet is a global network, policy implications are often local. In spite of this local nature of digital developments, there is a tendency to address them mainly as global issues. Limitations of a predominantly global approach are increasingly noticeable. For example, Facebook until recently did not have any representation in Myanmar in spite of the impact of local developments in this country on Facebook’s public policy image and policy. Another challenge is ‘policy laundering’ i.e. issues being moved from one to another level in order to increase the chance of their recognition, caused by the lack of ‘vertical’ policy coordination. A grassroot approach to digital cooperation could be highly effective since it anchors discussions in the local cultural context and encompasses issues that people can ‘refer to ’ in their everyday lives. ‘Policy elevator’ function: to ensure that policy issues are moved both ways (up and down) among local, national, regional and global levels

In the end, if we are to achieve optimal interdependence for citizens, companies, and nations, and to successfully negotiate difficult and complex trade-offs between political, economic, and social interests, we must reflect seriously and with the utmost clarity on a single large question: what we stand to gain from an interdependent Internet, and what we might lose if it becomes fragmented.

Key Questions

- What might be the cost of Internet fragmentation for nations, companies, and citizens?

- What would be the global implications of a more fragmented Internet for development, trade, and overall prosperity?

- What governance mechanisms will be required to ensure the beneficial local impacts of the Internet, and compliance with national laws, while maintaining and developing its global interoperability?

Previous Events and Initiatives

Events and Initiatives

- 75th anniversary of the United Nations (preparatory consultations and the UN General Assembly in autumn 2020)

- The humAInism project: AI tools for an AI social contract

- Follow-up process the report of the UN Secretary General’s High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow interdependence issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: UN High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation

2. Sovereignty

Predictions from January 2020

Sovereignty in the digital realm refers to the control exercised by (primarily) governments over tech infrastructure, digital platforms, and the collection and processing of data in specific territories. Digital sovereignty is exercised using tools ranging from the legal – court orders, for instance, and national regulations – to the technical, including Internet shutdowns and data filtering. Approaches differ from country to country.

For instance, China has achieved an unusually high level of sovereignty with its legal requirement that Chinese citizens’ and organisations’ data be stored on Chinese territory (i.e. localisation). GAIA-X is the EU’s initiative for developing its own sovereign cloud and digital ecosystem. The EU has also extended its sovereignty worldwide by requiring that the data of its citizens be processed in ways compliant with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) even outside the EU’s jurisdiction. Tim Berners-Lee’s Solid project focuses on the self-sovereignty of individual Internet users over their own data and digital footprint.

In the 2020s new tools and approaches will emerge, and a crucial task will be to maintain an optimal balance between localisation and cross-border co-operation. This balance can only be achieved by way of an approach based on collaboration, evidence and, above all clarity.

Key Questions

- How can we balance the needs for sovereignty and for cross-border co-operation in the digital realm?

- Which types of data, infrastructure, and platform should be subject to localisation policies? And what are the arguments for and against such policies?

Previous Events and Initiatives

Events and Initiatives

- 75th anniversary of the United Nations (preparatory consultations and the UN General Assembly in autumn 2020)

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

- Governments move towards new digital tax rules

- Privacy comes into focus as the number of investigations increases

- Antitrust investigations target tech giants

- Online rental businesses face pushback

- Facebook’s Libra attracts cryptocurrency regulatory concerns

- Huawei controversy sparks far-reaching implications

Analysis and Training

- Follow sovereignty issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Jurisdiction | Data governance

- Sovereignty issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance | Diplomatic Theory and Practice | Artificial Intelligence: Technology, Governance and Policy Frameworks

3. Governance

Predictions from January 2020

Governance comprises the policies, laws, and processes that steer digital development. In the 2020s, the main criterion for assessing the effectiveness of digital governance will be the extent to which legal and policy mechanisms can protect the rights, assets, and interests of citizens, companies, and countries in the digital realm.

Digital governance is in a transition period, and new approaches and solutions are urgently required to meet emerging realities. Citizens currently have recourse to little affordable protection in cases of hacking or deprivation of access to online platforms. Companies, especially small and medium-sized ones, have similarly limited options in asserting their legal rights on tech platforms that are becoming de facto markets unto themselves. Finally, nations are often unable to provide digital security in their own territories, which represents a clear failure to fulfil one of the fundamental mandates of government.

In sum, citizens, companies, and nations often do not have access to a governance space or mechanisms in or by which to raise and address their digital issues. In the search for a solution to these problems in the 2020s we will observe the following main trends:

First, digital governance discussions will increasingly be about more than technology itself. To take one pertinent example, the long-running dispute between Amazon and a number of Latin American governments over the .amazon domain name centres not on a technological issue as such but on questions of corporate intellectual property and cultural identity. The case is similar with 5G, data, and AI: these are all ‘technical’ issues that are fundamentally about larger legal, cultural, security, development, and human rights dilemmas (see the ‘building’ illustration).

Second, we will see existing governance and legal systems evolving to take digitalisation into account and to assert themselves in the digital realm. Many of these systems are elaborate edifices developed over centuries, however, and the task of adaptation entails serious challenges. The healthcare and medicine industry, for instance, will go through large-scale regulatory changes as it accommodates the effects of the digital revolution. Similarly, as autonomous vehicle technology advances the legal framework pertaining to transport will require wholesale revision. No governance sector will be left unaffected by digitalisation, and the specific needs of a number of fields will be addressed by Geneva-based organisations: health (World Health Organization – WHO), trade (World Trade Organization – WTO), humanitarian issues (International Committee of the Red Cross – ICRC, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees – UNHCR), air transport (International Air Transport Association – IATA), and so on.

Third, in the 2020s the ‘governance inflation’ will continue. For example, the way that cyber, data, blockchain, digital, and AI all prefix the word governance can lead to the perception that each of these terms represents a new type of governance, while in fact they often address fundamentally the same or similar policy issues. For instance, most ‘AI governance’ relates to issues that are encountered across the digital sphere and which have been discussed for decades: security, technological standards, e-commerce, human rights online, consumer protection, etc. Of course, AI does bring unique challenges to the centuries-old human-centred political, social, and economic order, such as ‘human hacking’ and increasing AI autonomy. But as we seek governance clarity in the 2020s, we should make a clear distinction between familiar challenges that historical precedents and existing frameworks can help us to tackle, and others that demand genuinely new approaches and systems. Reducing governance confusion should be the first step towards governing digital developments.

Fourth, it is likely that the need for a holistic approach will remain the ‘elephant in the room’ of digital governance discussions. Yet the need must be confronted collaboratively and imaginatively if we are to answer the fundamental question of how to govern inherently cross-cutting digital technologies across a wide range of policy silos. If we do not, it is inevitable that current governance confusions and even conflicts (at a national level between ministries, and globally between international organisations) will continue and accelerate. Various proposals for an international body to deal exclusively with digital issues are insufficient in this regard, not only because of political differences but because the impacts of digitalisation are so multiple and pervasive that any such organisation would find itself either replicating the work of the UN or in outright conflict with the UN in terms of coverage and mandate.

The UN High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation proposed the Internet Governance Forum Plus (IGF Plus) model as a pragmatic and effective route towards holistic digital governance. The IGF Plus would be a single forum where governments, citizens, and companies could gather to develop policies to govern aspects of digital technology via a Cooperation Accelerator, Policy Incubator, and Help Desk. The IGF Plus would build on an existing policy mandate provided by the Tunis Agenda of the World Summit on the Information Society, as well as on the experience and expertise developed at the IGF since 2006.

Key Questions

- How can we create mechanisms by which citizens, companies, and countries can address their digital policy issues in simple, affordable, and effective ways?

- Could the IGF offer a global space in which the full range of policy requirements could be discussed in multidisciplinary, multilateral, and multistakeholder ways?

- Which aspects of AI, data, and security require specific governance solutions?

- Would a digital helpdesk be an affordable solution for actors who cannot currently afford to ensure compliance with the requirements of a multitude of digital policy-making bodies, ranging from the UN and the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) to private standardisation bodies?

- How can actors from small and developing states be helped to navigate increasingly diverse and resource-demanding digital policy issues, discussions, and regulations?

Previous Events and Initiatives

Events and Initiatives

- 75th anniversary of the United Nations (preparatory consultations and the UN General Assembly in autumn 2020)

- 15th Internet Governance Forum (Katowice, 2–6 November 2020)

- International Congress for the Governance of AI (ICGAI) (Prague, 16–18 April 2020)

- POLITICO’s AI Summit (Brussels, 16–17 March 2020)

- The humAInism project: AI tools for an AI social contract

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow governance issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Interdisciplinary approaches | Artificial intelligence

- Governance issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance | Internet Technology and Policy: Challenges and Solutions | Artificial Intelligence: Technology, Governance, and Policy Frameworks

4. Diplomacy

Predictions from January 2020

Diplomacy will play an increasingly important role in managing relations and conflicts in the highly interdependent digital world of the 2020s. Superior both ethically and practically to hostility, conflict, and even outright war, diplomacy in all its forms is the only sane option for dispute resolution in the evolving digital space.

Official diplomatic services must be prepared to represent national interests in global negotiations over data, cybersecurity, e-commerce, digital taxation, and other fast-emerging policy issues. But currently very few countries have the institutional and human resources necessary to keep abreast of the more than 1000 policy discussions in progress across the globe, on questions ranging from technical standardisation and Internet infrastructure to cybersecurity, e-commerce, and human rights.

The continuing digitalisation of health, humanitarian, environmental, and development agendas and activities will also add dramatically to the pressure on diplomatic services to increase their digital expertise.

As a result, in the 2020s diplomatic services worldwide will undergo profound transformations as they equip themselves to comprehend and negotiate both digital issues per se (infrastructure, standards, etc.) and the digital aspects of health, trade, security, and other traditional policy fields. International organisations operating in these fields (the WHO, WTO, and UN, respectively) will have to adapt as well, principally by learning how to manage the tech-policy nexus and how to engage businesses, academic institutions, and other actors involved in shaping digital developments.

But the need for diplomacy is not limited to official diplomatic services. Non-state actors also need to cultivate diplomacy (some large tech firms are already building teams in this area), as a general practice and as a mindset for the management of relationships and conflicts within multiple existing and emerging communities in the digital world.

Sometimes ‘tool-use’ is termed ‘digital diplomacy’ and ‘topic-coverage’ ‘cyber-diplomacy’, but this itself leads to confusion: cyber tends to imply a focus on cybersecurity, while in fact diplomacy must meet challenges on a far broader range of issues, including infrastructure, human rights, the digital economy, and many others.

Key Questions

- While developed countries are relatively well positioned to adapt their diplomatic services to the fast-evolving digital policy field, the same cannot be said for developing countries. Is there a risk of excluding stakeholders from key international processes addressing existing and emerging digital policy issues? If so, what measures can be taken, and by whom, to empower such countries to stay engaged?

- Tech companies are increasingly eager to enter the realm of diplomacy by way of initiatives such as the Digital Geneva Convention and Digital Peace Now. Is it a good thing that the private sector is taking (or trying to take) a more active role in digital policy? Or should it be left to governments alone?

Analysis and Training

- Follow diplomacy-related issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Capacity development | Interdisciplinary approaches

- Diplomacy-related issues are covered in the following courses: Diplomatic Theory and Practice

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

5. Geopolitics

Predictions from January 2020

Geopolitics in the digital realm is currently dominated by economic, strategic, and military friction in the online realm between the ‘digital G2’ of China and the USA: contested areas include data, infrastructure, standards, platforms, and e-commerce. Meanwhile, other countries are working to establish their own roles and jockeying for positions in the new distribution of political and economic power. It is a cyber arms-race that will only accelerate in the 2020s as an increasing number of countries continue to develop offensive digital capabilities designed to manipulate, disrupt, or destroy information systems and networks abroad.

On the other hand, the last two years have also seen a move, mainly from western nations, towards transparency as to their military and defence cyber-capabilities. In 2019 France and the Netherlands, for instance, made clear their respective positions on the application of international law to cyber issues including self-defence, use of force, and state responsibility. In 2020 we can expect similar moves from other nations, and therefore greatly increased clarity on the larger digital geopolitical picture.

Key Questions

- Will a ‘third digital way’ emerge involving countries from Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America?

- Would a ‘digitally non-aligned’ group be empowered to propose and develop independent and innovative technical solutions capable of leveraging its potential in the digital economy?

- How to ensure that developing countries are not left behind in global digital policymaking processes?

Previous Events and Initiatives

Events and Initiatives

- G20 Leaders’ Summit (Riyadh, 21–22 November 2020)

- G7 Summit (USA, 10–12 June 2020)

- BRICS Summit (Saint Petersburg, Russia, July 2020)

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow digital geopolitics issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Cyberconflict and warfare | E-commerce and trade | Sustainable development

- Digital geopolitics issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance | Cybersecurity

6. Security

Predictions from January 2020

Security is a well-established policy field in the cyber arena, with its own vocabulary, a set of specific policy processes, and reasonably stable positions on the part of the main actors. In 2020 we can expect further progress as a result of parallel work to be undertaken by the UN Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) and Group of Governmental Experts (GGE). The OEWG will present its report to the UN General Assembly (UNGA) in September 2020, with the GGE doing the same in September 2021. While expectations are modest for both groups, each nevertheless serves an essential purpose by providing nations with a collaborative space in which to talk rather than fight.

Another group of governmental experts (GGE) will discuss emerging technologies in the area of lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS), focusing on questions legal, technological, and military. In 2020, GGE LAWS will concentrate on preparations for the Review Conference in 2021, where a decision should be reached as to whether the end-goal is a binding treaty prohibiting LAWS or if regulatory efforts should move in some other direction.

In the final months of 2019, the UN set in train proceedings on cybercrime whose end-result may be a UN Cybercrime Convention. As the voting for the relevant resolution shows (79 votes for, 60 votes against, 33 abstentions), this process will inevitably trigger new controversies, in all likelihood around the issue of whether a UN Cybercrime Convention is in fact required or whether universal adoption of the 2001 Budapest Cybercrime Convention would be sufficient (this was adopted in 2001 by the Council of Europe and currently has a total of 64 ratifications/accessions). In 2020, cybersecurity will be the focus of TechAccord, the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, and the Geneva Dialogue on Responsible Behaviour in Cyberspace, among other processes and initiatives.

Key Questions

- How to apply international law in cyberspace?

- Is there a need for an international treaty on cyberspace?

- Do states have a right to self-defence in cyberspace?

- Is a UN Cybersecurity Convention necessary or might the 2011 Budapest Cybercrime Convention be sufficient?

Previous Events and Initiatives

Events and Initiatives

- Preparatory Meetings of the UN OEWG and GGE (see calendar)

- Munich Security Conference (Munich, 14–16 February 2020)

- Geneva Dialogue on Responsible Behaviour in Cyberspace

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow security issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Cyberconflict and warfare | Cybercrime | UN GGE and OEWG | GGE on LAWS | Industry cyber norms

- Security issues are covered in the following courses: Cybersecurity | Introduction to Internet Governance | Internet Technology and Policy: Challenges and Solutions

7. Standards

Predictions from January 2020

Standards will be centre stage in the digital world of the 2020s. The ‘standardisation war’ between the USA and China over 5G and facial recognition standards will continue; new standards will be required in the as-yet uncertain field of digital identity as well; and standards are likely to become the principal mechanism for the implementation of ethical controls on innovations in AI. Moreover, as developments in precision agriculture, autonomous vehicles, and connected objects increasingly blur the lines between digital and traditionally non-digital sectors, digital standards are coming to apply to areas to which they previously did not, including transport, health, and food security. As a consequence they will have far-reaching economic and social impact, and may threaten to work to the benefit of some interests above others and to alter the balance of power between competing actors.

The growing importance of digital standards will result in new questions as to the legitimacy of standardisation bodies and their procedures, and ultimately about how to ensure that standards reflect the full diversity of economic and political interests. The 2020s will also see increased participation by diplomats and policy representatives in the work of digital standardisation bodies such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

Key Questions

- How to ensure that technical standards (in AI, data, Internet, etc.) reflect policy considerations in areas including human rights, security, multilingualism, etc.?

- How to build bridges and benefit from synergies between ongoing work on digital standards and the existing practices/mandates of health, food, transportation, and other standardisation bodies?

- How to ensure that standard-setting processes are optimally inclusive and diverse, both in terms of stakeholders and of perspectives, so as to ensure that the resulting standards do not favour the interests of some actors over those of others?

Previous Events and Initiatives

Events and Initiatives

- The IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems

- Internet Research Task Force – Human Rights Protocol Considerations Research Group

- ITU-T Study Group 13 – Future networks (with focus on IMT-2020, cloud computing and trusted network infrastructure)

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow standards-related issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Digital standards | Telecommunications infrastructure | Artificial intelligence

- Standards-related issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance | Internet Technology and Policy: Challenges and Solutions | Artificial Intelligence: Technology, Governance, and Policy Frameworks

Dealing with Tech-Hype

New developments in tech lead inevitably to hype and inflated expectations. As the Gartner ‘hype cycle’ shows, however, expectations then come up against the limitations of reality, and the tech’s real potential and impact is revealed at the plateau of productivity.

Massive Online Open Learning programmes (MOOCs) offer a perfect illustration of the hype-cycle. Heralded in 2012 as a panacea for the world’s educational problems, the reality has been somewhat different. MOOCs fell short according to a number of metrics, including students’ accomplishment rates and impact on learning in general. On the other hand, however, once the plateau of productivity had been reached it was clear that MOOCs had indeed helped to foster a culture and practice of online learning.

Another example is blockchain. Initially blockchain seemed to offer a mechanism for the promotion of trust in the digital sphere, and to promise solutions to a huge range of social problems, but excitement has since abated considerably (from over 200 mentions in the Economist in 2018, ‘blockchain’ was down to only eight last year). Nevertheless, significant potential remains: discussions are now focused on a few areas in which the tech could offer concrete solutions, such as procurement, the recognition of foreign qualifications, and in building trust and enhancing transparency in supply chains.

Following the inflated expectations of 2019, AI is likely to enter its disillusionment phase in 2020, as (for example) increasingly robust questions are posed regarding the limitations and shortcomings of machine and deep learning. One main challenge for policy-makers and the tech community in the 2020s will be to ensure that hype does not lead to wasted resources and policy confusion, yet that as much potential and optimism as possible survive new tech’s potentially dispiriting encounter with the limits of the possible.

8. Data

Predictions from January 2020

Data is often described as the ‘new oil’ or as the ‘lifeblood’ of twenty-first-century society, metaphors that testify to its profound impact on modern life. In 2020, general public awareness of the issues around data will increase as that impact becomes ever more clear, and as countries begin to view data as a national asset that requires careful regulation and management.

The flow and storage of data are already geopolitical, trade and security issues, and it is likely that the EU’s GDPR will become de facto global regulation as it inspires a proliferation of similar initiatives at national and regional levels. The principal challenge for all such initiatives is to address data governance in a multidimensional way that is able to balance sometimes competing imperatives: those of technological innovation, economic policy, human rights, and international law, among many others (see illustration).

Key Questions

- How to develop and apply adequate and appropriate regulation to specific types of data (personal, scientific, business, open, etc.)?

- How to incorporate data governance into traditional policy fields and practices (health, migration, trade, etc.)?

- How to address data governance issues in multidisciplinary ways?

- How will data regulation affect the use and development of AI?

Previous Events and Initiatives

Events and Initiatives

- 3rd UN World Data Forum (Bern, 18–21 October 2020)

- Road to Bern (a series of events in the run-up to the World Data Forum)

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow data issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Data governance | Artificial intelligence

- Data issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance | Artificial Intelligence: Technology, Governance, and Policy Frameworks

9. Human

Predictions from January 2020

Human impact is increasingly the ‘measure of all things’ in thinking about AI and digital developments generally. At least, that is the claim of the policy declarations and ethical codes of numerous nations and companies, and in 2020 a central challenge will be to ensure that these claims become policy reality.

Regulatory alignment with human rights frameworks will be the most certain way to ensure that the interests and core values of humanity are served by technological innovation and protected by its regulation. In 2020 the pace of regulatory development along these lines will accelerate, especially pertaining to the implications of facial recognition tech for privacy and human rights. It is expected that the EU Commission will introduce a 5-year ban on facial recognition in the first 100 days of its mandate. Previously sidelined proposals for the strict regulation of surveillance from two UN special rapporteurs (on the right to privacy, and on freedom of expression) are likely to receive serious consideration in 2020 as a result of the potential of facial recognition technologies to be abused in surveillance practices. In the summer, the French government and the World Economic Forum (WEF) will release a report on the use of facial recognition for security purposes and on the protection of civil liberties.

Key Questions

- What are the challenges faced in ensuring that existing human rights frameworks are applied to the development and use of AI and other advanced digital technologies? How should those challenges be addressed, and by whom?

- Are there regulatory gaps that need to be filled to ensure that the use of advanced technologies complies with human rights frameworks?

- To what extent can human rights considerations be embedded in the design/construction of digital technologies?

Previous Events and Initiatives

Events and Initiatives

- RightsCon Conference (Costa Rica, 9–12 June 2020)

- UN Human Rights Council 43rd, 44th and 45th Sessions (Geneva, 24 February – 20 March 2020, 15 June – 3 July 2020, and 14 September – 2 October 2020)

- Freedom Online Conference (Accra, 6–7 February 2020)

- Computers, Privacy & Data Protection Conference (CPDP) 2020: Data protection and Artificial Intelligence (Brussels, 22–24 January 2020

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

- Data breaches increase in number, reaching a new record

- Privacy comes into focus as the number of investigations increases

- Internet shutdowns threaten online freedoms

- As AI technology evolves, more policy initiatives emerge

- Facial recognition generates human rights concerns

- Digital technologies converge with other sectors

Analysis and Training

- Follow human rights issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Human rights principles | Artificial intelligence

- Human rights issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance | Artificial Intelligence: Technology, Governance, and Policy Frameworks

10. Ethics

Predictions from January 2020

Ethics, once a topic confined to philosophy departments, has now thoroughly infiltrated public discourse and company boardrooms – to the extent that there have been grumblings in policy circles about ‘ethics washing’. Of late, discussions have focused on gauging the potential impact of AI on society at large, and on the development and implementation of ethical principles to guide the online behaviour of Internet users, from private individuals to business and policy leaders.

While ethical principles are likely to vary from culture to culture, human rights treaties are legally binding international standards. If the current focus on the former detracts from efforts to uphold and promote the latter, standards of individual protection may be negatively impacted, and so it is essential that ethical principles are developed within existing human rights frameworks. Further, although tech businesses have thus far led discussions on AI and ethics, the key question remains of whether self-regulation on the part of firms will be sufficient or whether some soft regulation (via standards and guidelines) or even legal regulation will be required. Certainly, the EU will seek to influence global AI regulation as it has done with data regulation via the GDPR.

Key Questions

- How can we ensure the compliance of various emerging sets of ethical principles with existing human rights frameworks?

- How to assess the limits of self-regulation and identify situations when legal regulation is appropriate?

- How to ensure that self-regulation, soft regulation, and legal/governmental regulation are complementary and mutually reinforcing mechanisms?

Previous Events and Initiatives

Events and Initiatives

- The IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems

- The Council of Europe’s Ad Hoc Committee on Artificial Intelligence

- AI for Good Global Summit (Geneva, 4–8 May 2020)

- AAAI/ACM Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Ethics and Society (New York, 7–8 February 2020)

- EU Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI

- Beijing AI Principles

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow ethics issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Interdisciplinary approaches | Human rights principles | Artificial intelligence

- Ethics issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance | Artificial Intelligence: Technology, Governance, and Policy Frameworks

11. Identity

Predictions from January 2020

Identity is a pressing area of concern in digital discussions. Big tech firms, principally Facebook and Google, provide platforms for online identity by providing credentialed access to other digital platforms and services, and in their role as ‘identity brokers’ gain extensive access to personal data and a deep understanding of individual citizens’ economic, political, and social activities. It is this access that has come to underpin the business models of the leading tech companies.

Governments too are providers of platforms for digital identities. Following the introduction of India’s Aadhar system, other national digital identity programmes appeared in nations including Singapore, Bermuda, Sierra Leone, Uganda, and Guinea. The declared goal of most such programmes is to simplify access to online services and foster social and economic inclusion, but they have provoked vigorous resistance from organisations that advocate for privacy and citizens’ rights. Because the provision of digital IDs involves the collection and processing of personal data, states need to demonstrate that adequate safeguards are in place to ensure data security and privacy. In the absence of such safeguards, state systems risk becoming tools for surveillance and other abuses.

Discussions of digital identity have already begun to move beyond questions of functionality (principally how to provide the maximum possible number of people with an online identity) towards a more comprehensive approach that takes into account the full range of issues at play, including human rights, security, and commercial contractual law. This trend will continue and accelerate in the 2020s. On the international level, the World Bank’s Identification for Development (ID4D) initiative will focus on the nexus of development and digital identity, while the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) will focus on the legal issues raised by electronic signatures and other instruments of digital identity.

Key Questions

- How to balance the opportunities and risks of digital identities? Governmental digital ID programmes, for instance, have the potential to contribute to economic and social inclusion. However, they can also be a tool for state surveillance and other human rights infringements (through abuses or the social credit system, for example). What specific safeguards should be put in place to protect against these dangers?

- In some cases, digital ID solutions provided by governments can also be used as authentication and identification tools for digital services provided by private entities (banks, telecom companies, etc). While such an approach has the advantage of making things easier for individuals when it comes to online transactions, what could be the unintended consequences of such integration/interoperability between public and private systems?

Previous Events and Initiatives

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow digital identity issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Digital identities

- Digital identity issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance

12. Trust

Predictions from January 2020

Trust is a core thread in any social fabric: off- and online alike, all our relationships, transactions, and daily routines are based upon it. Yet as questions of trust have become ubiquitous in digital discussions, clarity about what they in fact refer to has been lost. In the 2020s, digital trust debates will be exercised above all by the following questions:

Why do we trust online? It is clear that trust in the digital world does not work along predictable or orderly lines of cause and effect. For example, although many have argued that the Cambridge Analytica scandal reduced trust in Facebook, in fact the use of the platform has not declined: on the contrary, the number of active Facebook users has increased. Similar trends are reported for many other social media platforms. Much more research and informed policy action will be required in the coming years in order to apprehend and take into account the full range of factors that are in play in citizens’ trust-relationships online.

How do we trust online? Trust is not always a ‘binary’ thing that we either have or do not have. Rather, it tends to be something we have to some degree and in different ways. The following graphic, based on Geoffrey Hosking’s analysis of trust in society more generally, is helpful in understanding the various elements, dynamics, and gradations involved in online trust.

Whom and what do we trust online? The question demands a tripartite answer.

- Trust in technology depends upon the reliability of our digital tools. Just as we rely upon our cars not to break down and to take us to our intended destination, we also trust computers, devices, apps, software, and other online technologies to perform the tasks we require of them daily.

- Trust in tech companies has come to hinge on issues of data and privacy, especially after the Cambridge Analytica affair and a number of other data breaches and scandals. But AI is prompting a new wave of discussions about the trustworthiness of tech companies, with a new focus on questions of ethics and the increasing concentration of power in the hands of a few giant corporations.

- Trust in governments and public institutions has been declining due to their limited ability to protect citizens’ rights online as they do offline. But an increasing amount of pressure is being exerted on governments to play a more prominent role here, especially in monitoring and regulating the growing power of the tech giants.

These are the pressing questions that will demand our attention in the coming years, and as we move into 2020 discussions of them must lead to concrete and implementable initiatives. One promising example of such an initiative is offered by The Swiss Digital Initiative’s development of a Digital Trust Label. This will provide guidance and transparency to users of digital services such as apps or websites, and will benefit companies and institutions by certifying their status as responsible actors in the digital space.

Key Questions

- Beyond simply calling for ‘restoring trust’, what concrete actions have been or should be taken to increase the level of trust in the digital world?

- What are the trust implications of privacy and security policies? For instance, should tech companies be encouraged to adhere to their encryption policies even in the face of back-door access requests from authorities in the course of official investigations? Or should we trust that governments will request information only in good faith?

Previous Events and Initiatives

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow trust issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Interdisciplinary approaches

- Trust issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance

13. Content

Predictions from January 2020

Content is well on its way to becoming the primary focus of digital policymaking. In 2020 the pressure on tech companies to get their content-policy house in order will only grow, nearly certainly along lines of trajectory familiar from 2019.

The first imperative in this respect, following incidents such as the Christchurch attack and Halle shooting, is to prevent the spread of harmful content and hate speech online. France, Australia, India, and Pakistan, among other countries, have introduced intermediary liability legislation to make tech platforms accountable for any harmful content they host, and more governments are likely to follow suit over the coming 12 months. On the international level the following initiatives are likely to gather momentum in 2020: the Christchurch Call, the UN/Interpol handbook for online counter-terrorism investigations, and the UN Secretary General’s team to define a global plan of action against hate speech.

The second urgency is to tackle online misinformation, especially in the context of elections and political campaigns. Tech platforms are already positioning themselves in this regard ahead of the 2020 presidential elections in the United States. Twitter took a significant step by banning the paid promotion of political content. Google’s new regulations reduce possibilities for micro-targeting, a capability that has been crucial to the success of several misleading political campaigns. Initially Facebook refused to interfere with political advertisements, but after increasing pressure it has pledged to consider measures to prevent microtargeting by political advertisers.

The third issue is deepfake technology, a serious threat that will only grow more widespread in 2020. Deepfakes are images and footage that have been falsified using neural networks and advanced video technology, and in 2019 early methods for combating them began to appear. Google and Facebook, for example, have built collections of fake videos and are making them available to researchers developing detection tools. Twitter is working on a policy to combat deepfakes and synthetic media on its platform. Other researchers have suggested the use of blockchain here. At the same time, the first wave of national regulations is emerging: in the US, for example, the state of California has criminalised the publication of false audio, imagery, or video in political campaigns, while China has introduced new legislation banning the distribution of doctored footage without proper disclosure that the content has been altered using AI.

Key Questions

- Should big tech platforms be made liable for the content they host? Section 230 of the United States’ Communications Decency Act specifies that they are not, but this and other existing legislation worldwide may need revision.

- Is there a need for international standards or regulation on content policy?

- How to balance content policy, human rights, and cybersecurity?

Previous Events and Initiatives

- Council of Europe Conference of Ministers responsible for Media & Information Society | Artificial intelligence – Intelligent politics: Challenges and opportunities for media and democracy(Nicosia, Cyprus, 28–29 May 2020)

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow content policy issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Content policy | Violent extremism | Liability of intermediaries

- Content policy issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance

14. Sustainability

Predictions from January 2020

Sustainability, whether environmental, social, or economic, cannot be achieved without the effective deployment of digital technology. There was an initial ‘digital shyness’ in the formulation of the sustainable development goals (SDGs), which made only one direct reference to ICTs (Goal 9.c.). But that has now given way to a recognition that tech will be a key accelerator in the fight against hunger and climate change as well as in the quest for gender equality. The attainment of all the SDGs will depend on digital technology to some extent, and in the 2020s data will play a central role in monitoring and reporting on their implementation.

In 2019 sustainability and digitalisation were the focus of considerable research and discussion, notably in the flagship report ‘Our Common Digital Future‘ from the German Advisory Council on Global Change. In 2020, one of the primary challenges will be to connect and co-ordinate the growing number of digitalisation and sustainability initiatives. The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) is working on building a digital ecosystem for the planet that aims to provide a governance framework for co-operation across businesses, governments, academia, and international organisations.

Key Questions

- How to improve data availability in developing countries and low-income regions, and to monitor and assess progress towards achieving SDGs?

- How to achieve effective interplay between environmental and digital policies?

Previous Events and Initiatives

- The Fifth UN Multi-stakeholder Forum on Science, Technology and Innovation for the SDGs (New York, 12–13 May 2020)

- UNESCO World Conference on Education for Sustainable Development (Berlin, 2–4 June 2020)

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development 2020 (New York, 7–16 July 2020)

- The 8th World Sustainability Forum (Geneva, 15–17 September 2020)

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow sustainability issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Sustainable development

- Sustainability issues are covered in the following courses: Sustainable Development Diplomacy: On the Road to Achieving the SDGs | Introduction to Internet Governance

15. Inclusion

Predictions from January 2020

Inclusion is a cornerstone principle of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and one that should guide all our efforts to ensure that no-one is left behind in the march into a brighter global future. We must make certain that all citizens, communities, and nations benefit from the historic transition to a digital world, and that special attention is paid to those groups that have historically been neglected or ill-served by technological progress, such as women and girls, those with disabilities, youth and children, and indigenous peoples.

In the 2020s, the challenges of digital inclusion will demand a holistic approach that is able to take into account all of the following policy areas:

- Access inclusion: equal access to the Internet, information/content, digital networks, services, and technologies.

- Financial inclusion: access to affordable and trustworthy digital financial and banking services, including e-commerce, e-banking, and insurance.

- Economic inclusion: facilitate all individuals’, groups’, and communities’ ability to participate fully in the labour market, entrepreneurship opportunities, and other business and commercial activities.

- Work inclusion: support and promote equal access to careers in the tech industry and elsewhere irrespective of gender, culture, or nationality.

- Gender inclusion: educate and empower women and girls in the digital and tech realms.

- Policy inclusion: encourage the participation of stakeholders in digital policy processes at the local, national, regional, and international levels.

- Knowledge inclusion: contribute to knowledge diversity, innovation, and learning on the Internet.

As we endeavour to find unified responses in this varied range of spheres, and as we are forced to make informed trade-offs between different goals and interest groups, clarity in our thinking about statistics and policy will be essential. Without it, we will be negligent in our duty to work towards the digital inclusion of the ‘next’ or ‘bottom’ billion of digitally excluded citizens of the world.

Previous Events and Initiatives

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Taxonomy of digital inclusion (forthcoming publication)

- Follow inclusion issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Sustainable development | Access | Inclusive finance | Gender rights online | Interdisciplinary approaches

- Inclusion issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance

16. Commons

Predictions from January 2020

Commons: the understanding of the Internet as a shared space or commons, a repository for human heritage that exists for the public good, has been a touchstone of digital discourse nearly from the beginning.

A wide range of digital artefacts can claim ‘commons’ or ‘public goods’ status, including core protocols (TCP/IP, HTML), critical infrastructure (according to a recent Dutch proposal), and the radio-frequency spectrum; data commons in particular will be central to discussions of the implementation of SDGs. The UN High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation called in its 2019 report for the establishment of a platform specifically for dealing with digital public goods in general and with data in particular. Other initiatives in this field include The Future Society’s AI Initiative and UN Global Pulse.

The most direct test case to date of the difficult interplay between public and private ownership online is that of the Internet Society’s sale of the .ORG registry to a private company. While the Internet Society made the case that it could invest the resulting income of US$1.35 billion into its activities, and thus that the sale would promote support for an open and public Internet, many organisations and individuals opposed the sale’s lack of transparency and argued that it represented an unjustified transfer of community assets into private hands.

Questions

- What are digital commons and public goods?

- The UN Panel recommended the creation of a platform for sharing digital public goods. How feasible is such a platform and what common goods would it include?

- If data is seen as a (digital) commons, what implications would this have for its governance (leaving aside privacy considerations, which are already the subject of privacy regulations)?

Previous Events and Initiatives

Events and Initiatives

- 3rd UN World Data Forum (Bern, 18–21 October 2020)

- Road to Bern (a series of events in the run-up to the World Data Forum)

Analysis and Training

- Follow digital taxation issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Taxation

- Digital taxation issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance | Economic diplomacy

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

19. Crypto

Predictions from January 2020

Crypto came to renewed prominence as an issue in the digital realm following Facebook’s announcement of its Libra cryptocurrency in June 2019. This triggered immediate policy discussions among governments and international organisations, as well as in the finance and academic communities. France and Germany expressed concern about the introduction of Libra, and the Bank of International Settlement (BIS) launched a research programme and enquiry.

Libra and similar currencies have considerable positive potential in that they promise to reduce transaction costs and foster economic inclusion. But they also bring threats that will dominate policy discussions in 2020. For example, if Libra comes to serve as a reserve or back-up currency it may undermine fiat currencies, in particular struggling ones from developing economies. Another issue is that Facebook’s vast user base may lead to the company achieving a market monopoly. In the coming year and decade, national governments and monetary authorities alike will as a matter of urgency work to develop regulatory frameworks for stablecoin, virtual currencies, e-money, and other related developments in online finance.

The developments around Libra prompted newly focused research programmes from international financial institutions including the Bank for International Settlements and G8 group, and from central banks worldwide on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs). China’s central bank announced the development of a digital version of the Yuan. Close behind were Sweden, France, and the European Central Bank, while the EU continued to evolve its approach to these developments in the digital economy. 2020 will see the appearance of the first CDBC pilot projects, and the rate of change is likely to be rapid in countries across the globe where the cash economy is already in decline.

Key Questions

- Due to the global nature of the Internet and the big-tech firms, regulation of digital currencies at a national level may not be sufficient. Thus the question is how best to develop international mechanisms to guard against the risks posed by such currencies without smothering innovation? This is especially important in the case of global cryptocurrencies, with their potential to be used for money laundering purposes and to interfere with the stability of sovereign currencies around the world.

- How quickly will new financial regulations and instruments pertaining to cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, and crypto-assets be recognised by and integrated with current policy frameworks?

- What will be the future role of banks and other traditional financial institutions?

Previous Events and Initiatives

- World Economic Forum Annual Meeting (Davos, 21–24 January 2020)

- Geneva Blockchain Congress (Geneva, 20 January 2020)

- UNCTAD’s eCommerce Week (Geneva, 27 April –1 May 2020)

- IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency (Toronto, 3–6 May 2020)

- The G20 Leaders’ Summit (Riyadh, 21–22 November 2020) (with one focus being big tech’s move into finance)

- Publication of the Financial Stability Board’s report on addressing regulatory issues of stablecoins (July 2020).

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

Analysis and Training

- Follow cryptocurrency issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: Cryptocurrencies | Libra cryptocurrency

- Cryptocurrency issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance

20. Platforms

Predictions from January 2020

Platform providers will face intense scrutiny in the 2020s on a wide range of policy issues, from privacy and data to consumer protection and market competition. Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple, and other big tech firms have achieved such dominance in global markets that they are already the focus of multiple monopoly investigations by competition authorities worldwide. Current antitrust efforts are certain to continue into the 2020s, and a survey of the currently ongoing enquiries gives a good idea of what we can expect to see with increased frequency.

Amazon is under investigation by EU competition officials looking into whether the company may be using sensitive sales data gathered from retailers on its platform to boost its own sales and marketing activities and preferentially advertise its own products. Similar questions are being asked in the USA, where the House of Representatives’ Antitrust Panel is investigating potential competition abuses on the part of the company.

For Apple, antitrust investigations are mostly related to its AppStore and the control the firm exerts over it. Spotify has submitted a competition complaint against Apple in the EU, claiming that it gives preferential treatment to its own music streaming services. This issue is also being investigated by the US Department of Justice and the Dutch competition authority. Similar complaints have been filed by the providers of parental control apps in the EU, Russia, and the USA.

In February, the Court of Justice of the EU will rule on Google’s challenge to an anti-monopoly ruling from 2017 which imposed a fine of €2.4 billion on the company for skewing search results to favour it over its rivals. If the original decision of the European Commission is upheld the EU’s antitrust policy will have been bolstered, with possible implications for similar investigations in the USA. There, a bipartisan coalition of attorneys general has launched an investigation into Google over potential anti-competitive behaviour, and India’s Competition Commission is looking into whether Google has abused its position in the mobile operating systems market there.

The US Federal Trade Commission has opened an investigation into Facebook over the firm’s acquisition of more than 70 companies, apps, and start-ups (including Instagram and WhatsApp) over the past 15 years. The company is also under investigation by a group of attorneys general over its acquisition practices, on the grounds that they may endanger consumer data, reduce consumer choice, and/or artificially inflate the price of advertising.

The 2020s will see the tech giants’ struggle for primacy continue, and increasing efforts from governments and international organisations to impose limits and controls on their activities and dominance. Whether the latter are able to do so effectively will be one of the most important digital governance questions of the coming decade.

Key Questions

- Most (successful) antitrust cases against tech firms end in a fine. The sums involved can seem considerable, but given the big tech’s vast resources how effective are fines in incentivising companies to refrain from anti-competitive behaviour?

- If fines are insufficient, what other solutions might we consider? Some have suggested imposing functional separation regulation on the Internet giants: would such a measure be both effective and proportional?

- Is the current legal competition and antitrust framework fit for purpose in the digital economy with its new business models and challenges?

Analysis and Training

- Follow platform-related issues on the GIP Digital Watch observatory: E-commerce and trade

- Platform-related issues are covered in the following courses: Introduction to Internet Governance | Economic Diplomacy

A look back | Relevant developments from our Year in Review 2019 report

21. Openness

22. Metaverse

2022 predictions are integrated in orange colour. we revisit 20 each of them dictionary and was initiated around 20 keywords. Welcome to 2020, and to our annual collection of digital policy predictions – with a difference. This year, the predictions are organised around 20 keywords into what we have called a dictionary. They also address a longer timeframe than that of previous editions: not just the year ahead, but the coming decade. Special thanks go to Sorina Teleanu, Dr. Abe Davies, Andrijana Gavrilovic, Marilia Maciel, Arvin Kamberi, and others who have contributed their comments and reflections. But our readers too can contribute: we would be delighted to receive your responses, both in answer to the questions posed in the survey below and in the form of more general critical comments and reflections. We would also like to invite you to our 2020 Digital Briefing on 28 January 2020: please join us in this important policy journey.

Click to show page navigation!