The purpose of this paper is to open up one field of inquiry, to set some cornerstones, to stir your curiosity and to propose some food for thought. In nature, this paper belongs to the realm of philosophical inquiry. Language will hereafter be treated under a threefold perspective, considered in its three dimensions of:

- interpretation,

- persuasion, and

- respect,

in other words: falling within the fields of hermeneutics, rhetoric and ethics. Under each perspective I shall work out some implications for diplomacy. Then, I would like to sort out how language could run into a pitfall in each of these three dimensions, while skidding into two extremes: either by its lack of or by its excess. Subsequently, I would like to highlight what kind of challenges and pitfalls diplomacy may have to face and should then handle, depending on each respective failure or excess.

Two short preliminary remarks: while developing those thoughts, some Mediterranean specificity will be paid attention to, with a peculiar reference to the monotheistic faiths: Judaism, Christianity and Islam, that have featured in its history and its culture.

The term “diplomacy” is hereafter mainly equated with structured approaches made by ruling bodies to manage conflicts of interests and avoid or end wars, mainly between states, without excluding international agencies. The situation referred to is overwhelmingly one of negotiation.

DIPLOMACY AS LANGUAGE

Language and Hermeneutics (Interpretation)1

Language is much more than just a tool or just an instrument, which we would then make use of, apply or mould to fit our meanings and express those in words. Language is indeed what sets the fundamental framework, what moulds us, what gives us to the world. When we talk of a mother tongue, that expression highlights that language, in the particular case of a specific tongue, is actually delivering us to the world. Language to that extent is man-making, society-making, culture-making. Language is of course prior to any diplomacy, shaping its world, setting the rules of the game: it is in short a “frame setter”.

It is also true that language is a tool, an instrument that presupposes a craftsman able to use it properly and even to adjust the instrument to its goal and purpose. The speaker uses a language, looks for a proper wording, shapes the proper expression. The diplomat aims at finding an expression that may be endorsed by both parties. In that sense, language is man-made, society-made, culture-made: a real arte-fact.

This is why different tongues may find some common meaning in what they refer to. They are like fingers pointing to the moon; keep in mind the Chinese expression: when my finger points to the moon, only the fool looks at my finger. That very situation makes it possible to reach an agreement between two parties speaking different languages. Translation is therefore not an impossible task, even if it always remains blended with treachery or inaccuracy – see the well-known Italian saying tradutor traditor – because ambiguities or connotation can never be fully sorted out and removed. The word “crisis” will always mean judgement and manifestation for a ancient Greek; danger as well as opportunity for a Chinese; catastrophe for a broker on Wall Street.

One single meaning is not encapsulated in one word for ever. There is no absolute stability in a given language. And even if some stability may be settled through professional expressions, the background belongs to culture, is ingrained with values, even prejudices. Writing, reading, speaking always means interpreting. There is no absolute meaning that would lay beyond interpretation.

That perception should not be unfamiliar to the Mediterranean cultures referring to one of the three monotheistic faiths, each of those religions rooted in a written text, a holy scripture that is constantly read and understood through interpretation. Judaism, Christianity and Islam are constantly referring to their holy scriptures, trying to capture their “true” meaning, starting with the translation from an older form of their own language to the contemporary form of it (as far as Hebrew, Greek, and Arabic are concerned) or from one original language to the one targeted by the translation. Those three cultures cannot get rid of interpretation as a constant task. Interpretation is the due process through which the meaning of the text becomes owned, articulated, the word made sense.

Implications for diplomacy:

- Diplomacy is constantly involved in the business of interpretation; diplomacy indeed overlaps with interpretation. Interpretation is ingrained in any diplomacy, encompassing interpretation of earlier agreements, of present wording, of technical expression, of diplomatic jargon.

- Diplomacy, to the extent that it provides building blocks for bridges between parties speaking more than one language, cannot be separated from translation.

- One should accept it positively and not dream of an absolute language beyond interpretation. Interpretation is not an avatar of language, it is the very nature of language.

Language and Rhetoric (Persuasion)2

Language goes much beyond its function of expressing meanings, beyond its role as mirroring or dressing reality in rosy colours. The intention or will of charming, captivating, of winning over the addressee is ingrained in language.

We all know that power, strength and attempts to dominate are like drivers acting throughout languages. Within the whole Mediterranean philosophical tradition, or traditions, rhetoric, along with logic, forms an integral subject of philosophy (just to mention here Aristotle, Saint Paul, the Stoics, Cicero, Averroes). Whereas logic is considered as the way to raise persuasion through the necessity of the argumentation itself, rhetoric is deemed as a way to reach persuasion through a mix of intellectual, logical and emotional considerations. Logic is mainly used by scientists and teachers, whereas rhetoric is a proper vehicle when politicians and lawyers are developing their views and arguments. Actually the English word “argument” truly encompasses those two different but neighbouring meanings of disputation and reasoning.

Even if logic and rhetoric have undergone ups and downs in the last twenty five centuries, they have never vanished from the stage. Rhetoric made an impressive comeback in the Renaissance and is far from being weakened today. To the contrary: the media culture calls indeed for a full-fledged rhetoric, and the recent American electoral show provides clear evidence of the importance of rhetoric in today’s politics. The advertising business is today completely full of rhetoric.3

Rhetoric is all-encompassing when it comes to negotiation: it comes before negotiation, exists during negotiation, and follows negotiation. Negotiation and diplomacy as a whole cannot preserve themselves from rhetoric, which is overwhelmingly active around negotiations as well as inside them.

Implications for diplomacy:

- Diplomacy means also trying to persuade, to charm, to move the other party to come to terms with us, and the other way round. One should not hold it in contempt or consider it as an unavoidable evil. It is quite a positive feature.

- There is no diplomacy without an attempt to demonstrate the advantages of an agreement and the disadvantages of a lack of agreement.

- A negotiator must feel him or herself as an attorney or a prosecutor, advocating in the same go his own country’s interests as well as the other’s interests.

- But he or she has also to take into account the competitive bidding of rhetoric in the domestic political arena as well as the political mileage sought from any domestic nationalist or even chauvinist rhetoric; he or she should also assess its bearing in the long run.

Language and Ethics4

Language is not only meaning but also word: word spoken to somebody, word given to somebody. There is no language without speaker and addressee, the addressee then in his/her turn is answering as well. No language can exist without acknowledging the face of somebody else, individual or community. Language and desire may well go hand in hand.

More importantly, language is only possible when the other is perceived and acknowledged as other, different, through a bond of responsibility. Globalisation does not start with economic interests but with ethical respect for each other.

Taking now into account the Mediterranean cultural legacy originating in the three monotheistic faiths, one may say that monotheism is (should be) as such a school of antiracism and “xenophilia”, in other words of respect and ethical standards through cultural and ethnical diversity.

Going even one step further, one could assume that those faiths might have given root to that perception that language invites the other to reply, offers to the other the status of responder. In each of those faiths, one notes that a word is set out, a word that cannot be not heard, nor replied to. That original word lays the foundation of human life. In that sense, language exceeds the sole dimension of “meaning” and “sense” and implies forced interaction and answer, ultimately inviting mankind to respect and equity.

Implications for diplomacy:

- Diplomacy as such aims to prevent war; to manage conflict of interests in a way that makes war improbable or that can postpone its outburst, to make possible a way out of actual war. But it may sometimes also pave the avenue towards war or provide fuel for never-ending conflicts. However, diplomacy relies indeed on the assumption that the other party is worth being talked to, is a peer, an equal partner with whom a fair deal may be reached.

- Even if diplomacy may take its inspiration from the Machiavellian approach, the importance of being bound to the other or of nurturing the feeling of a linkage with the other party, remains very high.

- No negotiation, no diplomacy is developed as long as the other party is viewed as a “non entity”. Diplomacy in its very nature is driven by the acknowledgement of the other party and by a deep concern for (sense of) equity.

FAILURES DUE TO LACK OR EXCESS

When diplomatic efforts do not pay due or sufficient attention to each of those three dimensions, then the risk may occur of over-emphasis or under-emphasis. The hereafter mentioned traps, pitfalls or failures originate in a total lack or excess: absence on one side, non-limitation on the other side, in other words, too little or too much of a positive dimension. This may ruin diplomacy, or in other words, fuel the risk of wasting negotiations, and even driving negotiations to a point of no return.

Lack or Excess of Interpretation

When interpretation is not given its due acknowledgement or when interpretation is considered as not necessary, superfluous, or a futile intellectual exercise, then the lead is taken by fundamentalism. In its original meaning, fundamentalism signifies considering any interpretation of the scripture as a treachery, a trickery or an intellectual superfluous exercise, because the meaning is obvious, thoroughly readable. Fundamentalism in fact is moved by the assumption that one can own the truth, that the truth is something that can be possessed, an object. To my mind one is here at a crossroads: to what extent is truth a possessed object, something that is owned or resembles a legacy, something we are indebted to, which we cannot possess? It is amazing to see fundamentalism flourishing all over the world, and not confined to religions. Look at present, hot debates turning around ultra-liberalism, globalisation and the WTO, the greenhouse effect and pollution, genetics and gene manipulation.

It may be enlightening here to recall the traditional Biblical tale of the Tower of Babel that points clearly towards the narrow proximity between singleness of language and pretension of full-power. In other terms, the deadly dream of a situation where mankind could get rid of any translation and any interpretation is indeed nurturing the totalitarian purpose.

When there is overemphasis on interpretation, the risk is of falling into absolute relativism, or endless reconsideration, far from any stable meanings, caught in a mirror walled room, where each statement is mirrored ad infinitum. Any statement is considered entirely subjective and therefore not able to provide some lasting ground for any agreement or any memorandum of understanding.

Implications for diplomacy:

- Negotiating with a party sharing a fundamentalist approach is not an easy job. Pre-set values and ready made judgements of the other impede any flexibility, but more deeply, there is no acknowledged otherness. There is a fixed image of the other’s interests and perception as well as one’s own interests and self-image.

- Negotiation proceeds similarly, but differently, with a party sharing an absolute relativism: this is the kind of feeling felt while handling Russian dolls, when each meaning is hiding the next one, in an endless structure of slices; the perspective of permanently reopening the case and revisiting the draft agreement. Or as it sometimes occurs: starting negotiations after the signing of an agreement!

- Negotiation definitely looks easier when a middle point is reached where interpretation is considered as part of the game by both parties.

Lack or Excess of Rhetoric

When rhetoric is not considered as important and necessary, then the risk is that no interests, ours as well as the other’s are acknowledged. The pitfall is neutrality in the sense of flat profile, anorexia, lifelessness, faintness, or a self-defeating attitude. Nobody to persuade, no cause to advocate, no alliance to build and strengthen, no enthusiasm to raise. Flat land!

To a certain extent, it may also originate in a culture-bound impossibility of setting out a clear “no” to the other party. As “no” cannot be said, what is the value of a “yes”? How can a negotiator guess the breaking point of a partner who cannot express it in crude terms? Sensible interpretation is strongly required in such a case.

On the contrary, when rhetoric is overrated, goes beyond its limits, then persuasion becomes an end in itself and the other is used as an auditor bound to keep silent, not treated as equal. A kind of fascination develops that no achieved persuasion endeavour can satisfy oneself. Overbidding is followed by manipulating and demagogy, sustained through systematic lying. Cold blooded manipulation tends to become usual: persuasion for the sake of persuading; lying as the vehicle of power, influence, demagogy and domination. The emotional part of the reasoning offsets the logical part of it. The danger, of course, is that lying is never a long-term investment. Sooner or later, but for sure, it is revealed as a sort of quicksand foundation for any mutual agreement.

The policy of adopting the worst line could be linked to rhetoric and considered the result of negative rhetoric; the virtue of a no-agreement solution is then rhetorically enhanced and good marks are switched from a reasonable, reachable consensus to a new, ideal situation created through a temporary worsening of the present.

Implications for diplomacy:

- Negotiating with a party sharing a low-key approach is not an easy job. You may not assess the true cost of any concession on one side, and may feel floating as to the solidity of any consensus reached after due negotiations.

- Equally with a party that cannot express its disagreement by expressing a clear “no”, “not negotiable”, a skilled negotiator has to guess where the limit is implicitly set, at the risk of seeing the case re-opened or never closed

- Negotiating with a party resorting to endless manipulation and demagogy – not to say to lying – requires a lot of know-how, strong values, wisdom and perspicacity. Short-term demagogical manipulations need to be identified and distinguished from long-term endeavours based on shared interest. Even if rhetoric is part of the game, one should be able to handle the heart of the matter rather than grasp at shadows. An attempt to counter manipulation with manipulation, may well end up, through escalation, in sheer power games and disregard for the substance of negotiation.

- Negotiating with a party speculating on a worsening of the present situation to attain an ideal arrangement is hard to achieve through reasoning and submitting objective or plausible considerations, because the driver is more on the emotional than on the logical side; it requires from a negotiator the capacity to re-frame the situation and start from a completely different square one. A balanced mix of logic and rhetoric makes negotiation easy and even pleasant.

Lack or Excess of Ethics

Basically ethical standards are not complied with, as soon as the “otherness” (the other as compared to myself) is felt as negative, disparaging, a lack of, or when “other” can not rhyme with “equal”. What distinguishes the other from me, his/her position from mine, is then ignored, taken as of no importance. There is eventually no “other”, no “partner”. Paternalistic attitudes are not far away, then: despise and – further away – cynicism and totalitarianism.

It is not uncommon today to see states resorting to “demonisation” of other states or organisations; such behaviour clearly indicates that the room for negotiations is becoming tiny and that interaction on an equal footing is loosing ground.

When ethics is over emphasised, then a kind of suffocation or paralysis could result because of several reasons:

- The importance given to specific values or behaviour offsetting the joint achievements and postponing the confidence building experience of joint successes, even small. That may be found when a partner, based on ethical consideration, is overly stressing attitudinal aspects, cultural differences, be it rooted in social classes, values, worldviews (the well-known German expression “Weltanschau”), making the gaps unbridgeable or overemphasising the moral commitment;

- Interpersonal direct relationships may be substituted for mediated social relationships, giving love an edge over justice, playing down the collective, social mediations and overlooking the fact that the relationship between and among societies or corporate entities does always materialise through third parties in a triangular set up;

- Neglecting the element of tragedy in human history and playing down the fascination exerted by violence, in the name of moral standards.

Implications for diplomacy:

- Diplomatic negotiation where one party is denied the quality of human being or human society may be bound to fail because the minimal requirement of respect and due consideration is missing. Demonisation is bound to fail, to the extent that it acts as a rhetorical denial of the other party.

- When a party is moralising about the behaviour of the other one or when terms under negotiation are put under a moralist perspective, talks may become paralysed – high standards cannot be met – or may be distorted, set on a wrong footing in a sense that individual ethics are always running short when one comes to societal problems.

- Once again, proper conditions for sound negotiations are the ones of mutual respect and due consideration for “otherness”.

To summarise it in key words:

The context of negotiations may differ quite a lot. In each of the three dimensions, the point of gravity or poise may be set in the middle equilibrium or in one of the extremes.

Typology

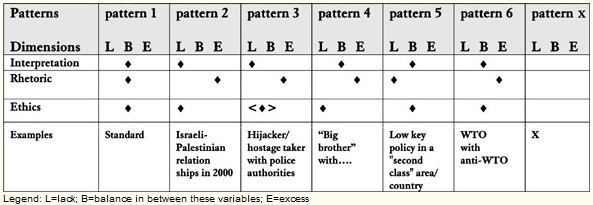

As an aide to typify profiles or patterns of diplomatic language and to visualise them, the following table is submitted for your appraisal, at the risk of being sketchy and superficial:

Patterns 2, 3, and possibly 4, may represent the most frequent pitfalls in our present era.

Such a typology is useful not because it fully matches with reality, always fluid, mixed up and moving, but because it provides a frame of analysis and reminds us that the remedy has to fit to the specifications of each pattern. The diplomat who handles a case 2 like a case 5, may shorten his/her own career!

In order to negotiate a fair and lasting deal, when the starting situation is at an extreme position, the aim is to make it possible to move towards the “middle”. A skilled negotiator should be able to make it.

Critical Thresholds

Remedial measures presuppose that there exists a specific level beyond which a slippage into fundamentalism, manipulation or denial is taking place, or to the contrary a move from an extreme to a more balanced situation. Measuring as such is hardly possible because cultural ingredients as well as interpersonal chemistry are brought into play, and also because the continuum is not of a “quantitative” nature. Nevertheless there are qualitative criteria that may help the diplomat to guess and feel where the critical thresholds are placed, such as:

- rebuke of any interpretation by the other party, or attempt to play on ambiguities and meanings;

- endless reopening of negotiations, postponement of any initialling of draft agreements;

- manipulation for the sake of manipulation, without any attempt at convincing the other;

- absence of any real interaction between negotiating parties;

- demonisation or even denial of any diverging opinions;

- overuse of moral qualifications or considerations;

- absence of any acceptable, realistic and concrete proposal.

These features may provide a clear signal that something is set on a wrong footing in the negotiation.

WAYS OUT OR THE BALANCED TRADE-OFF

Full-fledged, professional diplomatic language with substance and future means that a sufficient and balanced importance is given to each of the three dimensions: interpretation, persuasion and ethics, and within each that a reasonable equilibrium is reached, far from the extremes. Pattern 1 is the standard that should be arrived at if required even through a long and arduous endeavour. It allows effective negotiations that may really focus on divergences, risks, costs and mutual concessions.

Basically, diplomats are the ones who have to find a practical way out of dead-ends and can feel what strategy works, and what tactics do not work in a given situation.

Nevertheless, I will not quit too early and give up the crux of the matter. Without resorting to quick-fix or blue-print solutions, the following guiding principles should be borne in mind.

- It is not within a diplomat’s reach to set in advance a proper balance and decide about optimal requirements. How the balance is set depends mainly on the surrounding reality, the nature of the interaction, and on past experiences. Any situation is specific to itself, given as well as evolving. It does not help to blame reality for not matching the books. The key is to work it through.

- Interpretation being a must, inter-subjectivity is the proper path between subjectivity and objectivity that are both unattainable (E. Husserl). Inter-subjectivity needs patience, constant effort, permanent dialogue, tracking the perception developed by the other party and building up a common future.

- The diplomat has to be particularly alert about thresholds, when a “negotiation game”, so far overwhelmingly framed by a sound openness to interpretation or a normal use of rhetoric, is suddenly or imperceptibly sliding into, let us say, fundamentalism or relativism, sheer manipulation or despise. Awareness and perspicacity are definitely critical assets in such situations.

- Countering manipulation with manipulation or fundamentalism with fundamentalism will lead only into a deeper dead-end, that will only catch and jam the process in a symmetrical escalation of a “more of the same” kind! Similarly a deep relativism, the opposite of fundamentalism, does not help. Like in judo, the way out does not consist in counterpoises but in moving the centre of gravity. When in one dimension the situation has moved to one extreme, a solution might be to concentrate on another dimension in order to reach or consolidate a balanced position there.

- Ethics are critical. When “otherness” is no longer acknowledged, war is not far away. Then a move towards extremes may start in the other two dimensions: mainly manipulation and fundamentalism. Ethics require getting rid of contempt, of negating but also being free from any fear in front of the other party and from any complacency. An effective way of redistributing the cards may be human authenticity and moral quality.

- Experience of negotiating with hijackers shows the vital importance of keeping or developing a bond, in particular through the process of naming, as well as of disclosing that some concerns of the violent party have been interpreted and understood – that does not mean accepted or agreed upon.

- While facing heavy pressure, even violent pressure, a diplomatic way out may be to make it explicit and display it, and ask openly whether the other party intends to persist. In other words, balanced rhetoric, balanced ethics, and a frank question about interpretation. Soft power may well win over hard power.

Now it is up to diplomats to illustrate these reflections with case studies and to come up with their practical experience of the aforementioned theoretical framework. They are the ones who can check whether these theoretical considerations stand up to the test of reality or not.

ENDNOTES

1. See the school of thought inspired in Germany by Hansgeorg Gademer and in France by Paul Ricoeur.

2. See the contemporary school of new rhetorics emphasising action on the minds of the hearers: Kenneth Burke, Edwin Black, Chaïm Perelmann and others.

3. Two instances gathered from recent ads: “Why should the UBS bank become your partner?” Because of its symbol: the conductor was skilled enough to manage together harmony and diversity (United Bank of Switzerland, TV spot in January, 2001). “Why should a Peugeot car be worth purchasing?” Because you should “stop liking and start loving.” (Peugeot TV spot in January, 2001).

4. See the whole work of Emmanuel Levinas, but in particular: Totalité et Infini (1965) and Difficile Liberté (1963).