Ancient Greece is considered the cradle of European civilisation. Greek notions of rational thought, argumentation, and competition are the foundation of the way we think today. As the renowned British philosopher A.N. Whitehead once stated, the European philosophical tradition consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.

In Greek politics, democracy was developed through the battle of ideas and the exercise of power, with the aim to gain trust and support from those who vote. Despite this, the idea of ‘common peace’ from Ancient Greek diplomacy was one of the founding principles of the League of Nations and the Charter of the United Nations. Modern sciences also owe much to the ancient Greeks as it was here that philosophers and scientists developed comparative testing methods. Theatre, geometry, and astronomy also originated in Greece, as did the terms ‘diplomacy’ and ‘technology’.

What is the etymology of ‘diplomacy’?

The term ‘diplomacy‘ derived from the ancient Greek δῐ́πλωμᾰ (diplōma) composed of diplo (‘folded in two’) and the suffix -ma (‘an object’). The folded document granted privileges to the bearer, often as a permit to travel. Later, the term diploma was borrowed by Latin meaning an official document. In the 18th century, the French term diplomate referred to a person authorised to negotiate on behalf of the state, and corps diplomatique referred to officials involved in foreign policy. In 1796, the term ‘diplomacy’ was officially introduced into English by philosopher and political scientist Edmund Burke.

What is the etymology of ‘technology’?

The term ‘technology’ derived from the ancient Greek τέχνη (techne), meaning skill, art, trade, and the suffix -logia (science, knowledge), translating into the ‘science of craft’. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle defined techne as a ‘rational faculty exercised in making something’ and ‘a productive quality exercised in combo with true reason’. Aristotle believed that the goal of techne is to ‘bring something into existence which has its efficient cause in the maker and not in itself’. It is also important to note that Aristotle related techne to the crafts and sciences, most notably through mathematics.

Among historians, there is an ongoing debate whether Ancient Greece was an advancement or regress in the development of diplomacy in comparison to earlier practices from ancient Egypt and Persia. Prof. Raymond Cohen, a leading historian of diplomacy, stated that ‘the practice of Greek diplomacy was quite rudimentary’ and ‘compared with Persian cosmopolitanism, Greek diplomacy was provincial and unpolished’.

Ancient Greece

Located in southeast Europe, Ancient Greece presented the bridge between Asia and Europe. This fact is important for understanding the overall interplay between Greek diplomacy and war. Greece also had over 1,000 city-states (polis) which were independent states, but also interdependent, which created fertile ground for diplomacy. Additionally, the balance of power was well developed in Greece.

Timeline of Ancient Greece

- Archaic period: Before 5th century BC

- Classical period: From 5th to 4th century BC

- Hellenistic period: From 4th to 2nd century BC

Important facts about Ancient Greece

For understanding ancient Greek diplomacy, it is useful to understand the social and cultural realms of this civilisation.

Mythology

Oratory

Writing

Diplomats in Ancient Greece

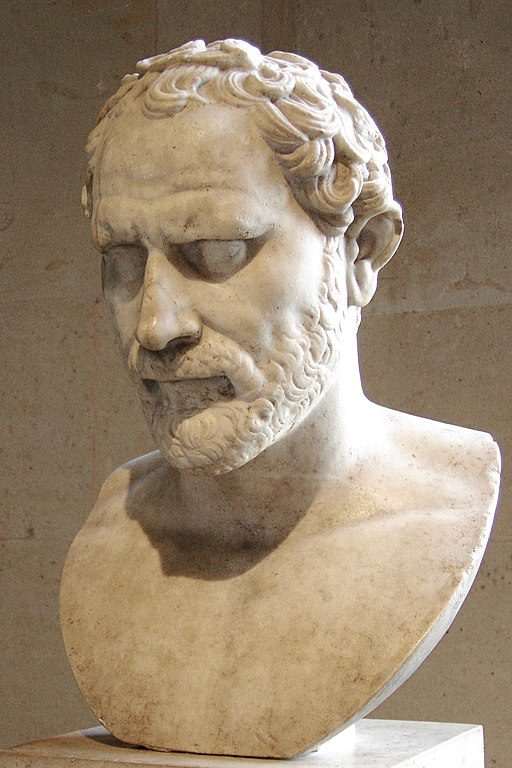

A proxenos (pl. proxenoi) was a Greek consular agent, and a citizen of the city-state in which he resided, not the city-state that employed him. As envoys, proxenoi had a task of gathering information, but their primary responsibility was trade. Proxenoi were a type of early honorary consuls, ambassadors, and lobbyists. A proxenos would use whatever influence he had in his own city to promote policies, friendships, and alliances with the city he represented. He was expected to handle all high-level political matters, as well as to provide support and housing for visitors from the sending state (merchants, representatives, politicians). Proxenoi were granted certain immunities such as asylum in case the sending state turned against him, or free and safe travel during both peace and war. The position of the proxenos held prestige and was hereditary. During the classical Greek period, it is probable that all well-known Athenian politicians held one or more positions as proxenoi (for example, Demosthenes was a proxenos in Athens for Thebes).

A presbus (pl. presbeis) or envoy, was a senior citizen involved in advocacy, similar to a public diplomat. Presbeis were great orators who went on unpaid, ad-hoc missions. Delegations of envoys were often big, numbering 20–30 people. They were prominent representatives of the sending states. In many cases, they used to address the citizens and senate of the receiving state, and tried to persuade the elite of the receiving state about the position of their country.

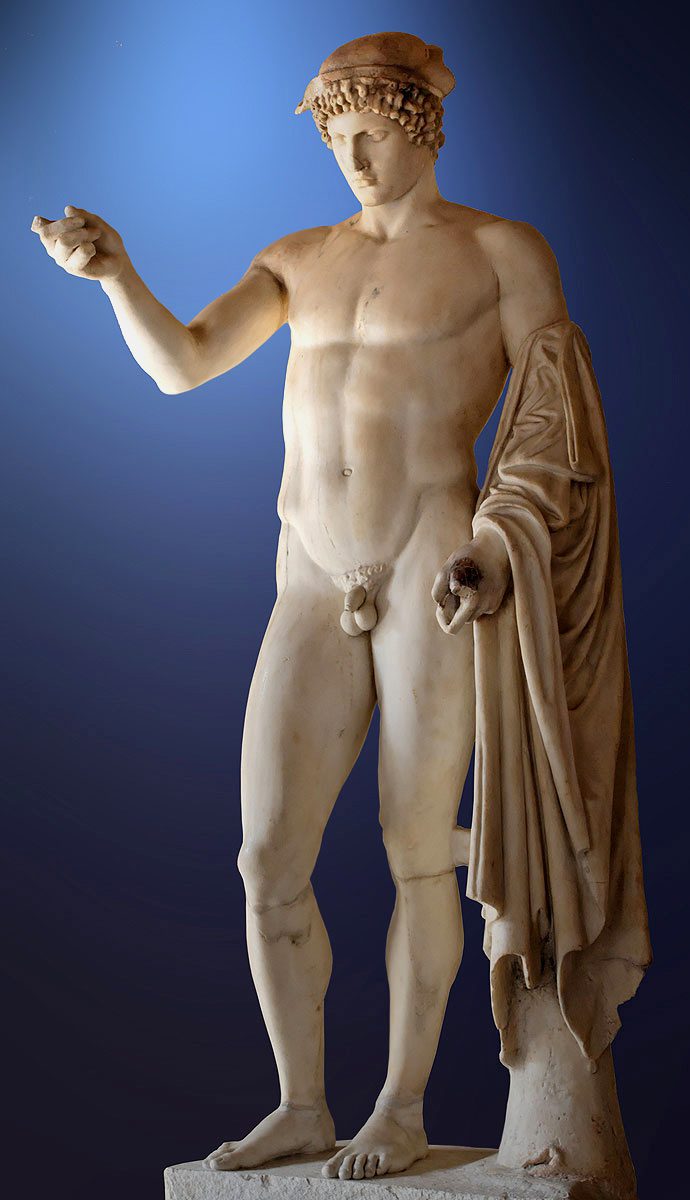

A keryx (pl. kerykes) was an inviolable Greek messenger. In Homer’s time, the kēryx was simply a trusted attendant or retainer of a chieftain. The role of kerykes expanded to include: acting as inviolable messengers between states even in time of war; proclaiming meetings of a council, popular assembly, or a court of law; reciting the formulas of prayer in important meetings; and summoning persons to attend. They were regarded as the offspring of Hermes. Kerykes were general-purpose messengers and masters of ceremonies. The diplomatic responsibilities of the heralds were to serve as a ‘truce-bearer’ prior to the start of the Panhellenic Games and to make announcements there. More important was their task of going ahead of ambassadors in order to secure guarantees for their safe reception. They were also responsible for issuing ultimatums and declarations of war. Heralds were the early masters of protocol.

Diplomatic innovations in Ancient Greece

Early multilateral diplomacy

Early multilateral diplomacy was developed around the idea of truce during the Olympic Games and other common festivities. At that time, the representatives of city-states used to gather here. It was also a moment when they shared a common identity, and a good opportunity to negotiate. The diplomatic innovation of Common Peace was born here, and included the permanent peace between the Greek city-states. The idea of common peace can still be found today, and was one of the founding principles of the League of Nations and our modern system which is based on the Charter of the United Nations.

Multilateral diplomacy occurred to a greater extent in the states-system’s religious leagues (neighbouring communities sharing a deity) and large-member military alliances (or ‘leagues’) established for defence and offence. One of the examples of the well-developed multilateral alliances is the Second Athenian Confederacy, a defensive alliance created in 378/7 BC. Its purpose was to guard against the growing fear that Sparta would not honour the common peace of the Greek cities. The famous Decree of Aristoteles described its purpose and defensive character, and invited others to join, including any ‘barbarians’ (non-Greeks) on the mainland or islands.

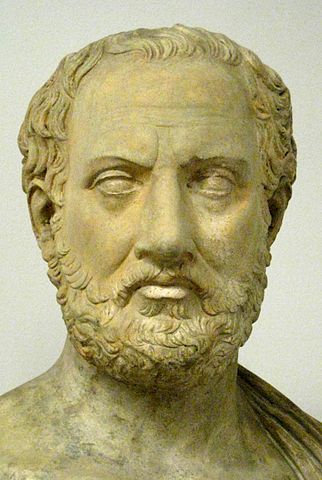

Steganography

Dating back to the 5th century BC, steganography is one of the oldest methods of concealing secret information. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, it was first used by the tyrant Histiaeus who shaved the head of a servant before tattooing a message on his scalp. When the hair had grown back, the servant was sent to deliver his message – a warning of an attack by the Persian army – which was revealed when the servant’s hair was once more shaved off.

Cryptography and early telegraphs

In the 2nd century BC, two engineers, Cleoxenes and Democletus, invented a system for conveying messages by using a type of cryptography called pyrseia (pirsos – torch). They created the 5×5 pyrseia table which listed all the letters of the Greek alphabet.

With the help of 10 torches, this table was used for sending messages between Greek towers (phryctoria). Two groups of torches were used: 5 for the table rows and 5 for the columns. With each letter corresponding to a row and a column, senders would send messages letter-by-letter. For example, for signalling the letter ‘N’, the sender would light 3 torches for the third ‘column’ and 3 torches for the third row. These messages would be passed on from tower to tower until they reached the message recipient.

In his tragedy Agamemnon, Aeschylus described how the message about the fall of Troy arrived from Troy to the city of Argos (c. 600 km) in just a few hours:

LEADER: Say then, how long ago the city (Troy) fell?

CLYTEMNESTRA: Even in this night that now brings forth the dawn.

LEADER: Yet who so swift could speed the message here?

CLYTEMNESTRA: From Ida’s top Hephaestus, lord of fire, sent forth his sign; and on, and ever on, beacon to beacon sped the courier-flame. From Ida to the crag, that Hermes loves, of Lemnos; thence unto the steep sublime of Athos, throne of Zeus, the broad blaze flared. Thence, raised aloft to shoot across the sea, the moving light, rejoicing in its strength, sped from the pyre of pine, and urged its way, in golden glory, like some strange new sun, onward, and reached Macistus’ watching heights. There, with no dull delay nor heedless sleep, the watcher sped the tidings on in turn, until the guard upon Messapius’ peak saw the far flame gleam on Euripus’ tide, and from the high-piled heap of withered furze lit the new sign and bade the message on. Then the strong light, far-flown and yet undimmed, shot thro’ the sky above Asopus’ plain, bright as the moon, and on Cithaeron’s crag aroused another watch of flying fire. And there the sentinels no whit disowned, but sent redoubled on, the hest of flame swift shot the light, above Gorgopis’ bay, to Aegiplanctus’ mount, and bade the peak fail not the onward ordinance of fire. And like a long beard streaming in the wind, full-fed with fuel, roared and rose the blaze, and onward flaring, gleamed above the cape, beneath which shimmers the Saronic bay, and thence leapt light unto Arachne’s peak, the mountain watch that looks upon our town. Thence to th’ Atreides’ roof-in lineage fair, a bright posterity of Ida’s fire. So sped from stage to stage, fulfilled in turn, flame after flame, along the course ordained, and lo! the last to speed upon its way sights the end first, and glows unto the goal. And Troy is taken, and by this sign my lord.

The basic pyrseia table was further advanced. One of the most popular variants was the Polybius square, developed by the historian Polybius.

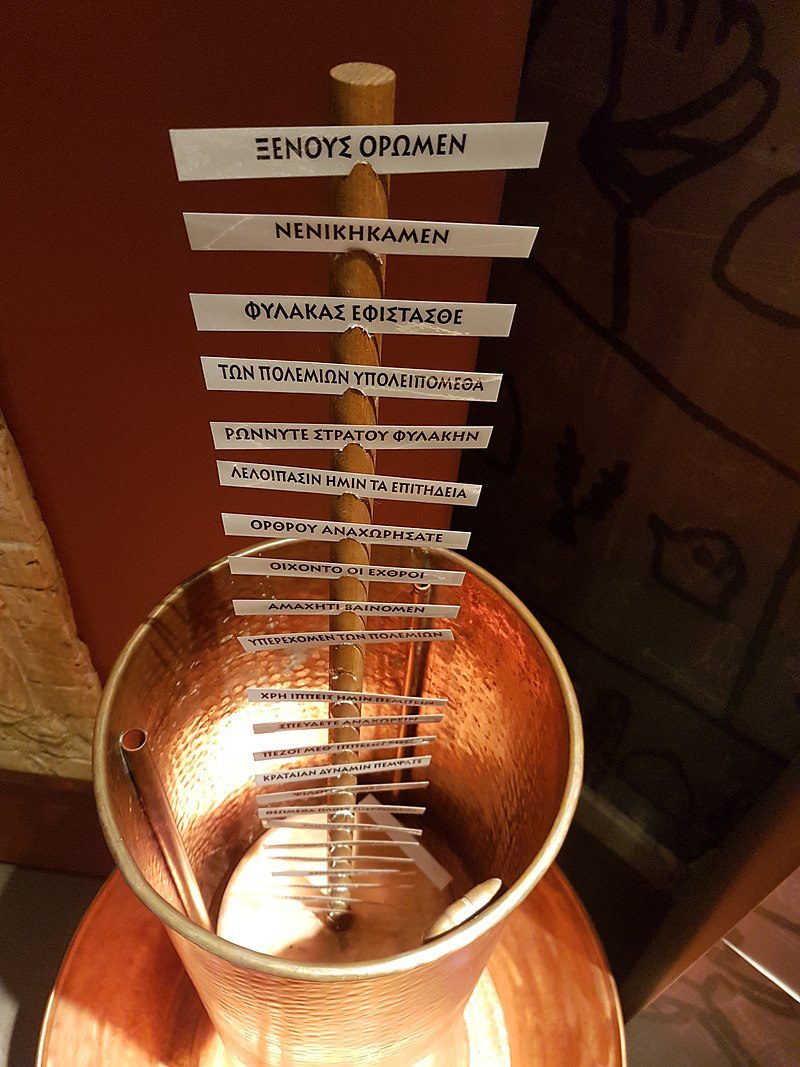

Another Greek messaging invention was the hydraulic telegraph. According to Polybius, Aeneas Tacticus invented it around 350 BC. It was a semaphore system that was later used during the First Punic War to send messages between Sicily and Carthage.

Source: Thessaloniki Science Center and Technology Museum.

Messages attached to rod. Thessaloniki Science Center and Technology Museum.

The system involved two identical containers filled with water in which there were identical messages attached to a rod. (The rod was fixed to a floating cork.) To send a message, the sending operator would raise his torch to signal the receiving operator. After this, both operators would simultaneously open a tap at the bottom of the container to drain water until the water level reached the intended message. The sender would then lower his torch and both operators would close their taps.

Diplomacy and democracy: An early tension

A strong focus on openness and transparency is one of the parallels between ancient Greece and our era. Ancient Greek diplomacy was one of the most open diplomacies ever practiced. Envoys addressed public gatherings in receiving city-state by using the arts of persuasion and rhetoric. They publicised important treaties by inscribing them on stone or bronze pillars (stelai) which were located in temples or other sacred places.

Paradoxically, at least at first glance, this openness created one of the major weaknesses of ancient Greek diplomacy. Facing the foreign public, envoys were advocating more than negotiating. Their task was to persuade the wider population of the receiving state, not to negotiate compromise with the opposite side. Today, public diplomacy on the internet also focuses on advocacy. However, major diplomatic breakthroughs are usually achieved via ‘translucent diplomacy’ where the public is aware of the negotiations and their results, but does not follow the process as it unfolds.

Today’s discussion about e-diplomacy and its demands for full transparency must consider the primary purpose of diplomacy: to achieve peaceful solutions for conflicts through compromise. Often, it is not possible to achieve compromise while negotiating in the public eye.

Modern diplomacy cannot, and should not, tolerate secret diplomacy. However, some form of ‘translucent’ diplomacy is often more effective in reaching compromise solutions than today’s, often choreographed, public diplomacy which is increasingly being conducted online. This is at least one historical lesson that we can learn from ancient Greek diplomacy.

Meanwhile in …

…China

The Qin dynasty (or Ch’in dynasty) ended the Warring States period and managed to unite most of the country for the first time in 500 years. This was the first dynasty of Imperial China, lasting from 221 BC to 206 BC. Despite its short reign, the Qin managed to establish a highly centralised government, and develop a legal code and written language. These are just a few of the great achievements which had such a lasting effect that they gave the county its name – China.

Emperors of the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD) governed according to Confucian principles. The Han governed for four centuries, consolidating unity. This was remembered as the golden period of China. During the Han dynasty, diplomatic relations with many different Asian states were established. All of those countries received Chinese ambassadors. Diplomacy was used to secure trade routes through less civilised regions to the west, and the famous Silk Road towards Europe (Roman Empire) was established, as was the sea route to India.

Chinese diplomacy in this period was mainly influenced by three thinkers. The semi-legendary Sun Tzu through his military treatise The Art of War which advocated diplomacy, negotiations, and cultivating relations with other nations as essential for the benefit of the state. Even more important were the ethical teachings of Confucius (551–479 BC) who preached respect for superior states, the observance of legitimacy of authorities on various levels, and the distinction between the cultured Chinese and the ‘barbaric’ foreigners. Confucius also praised rituals and protocol. In the end, the teachings of an earlier philosopher, Mencius, stated that the best way for a state to exercise its influence abroad is to develop a society worthy of emulation by admiring foreigners.

…India

The Maurya Empire (322–185 BC) in India reached its apex during the reign of Ashoka the Great (269-232 BC) who ruled over most of the subcontinent. Ashoka was a keen Buddhist and, apart from promoting the religion in his own realm, he also sent diplomatic missions to the Hellenistic kingdoms of Asia to spread the dharma (‘cosmic law and order’), a set of political and moral ideas, though this was most probably done for the sake of expanding and promoting trade and political influence. Such contacts continued for the next millennia, until the Rajput kingdoms (8th century) again isolated North India.

The history of drinks: Diluted wine

Ancient Greeks loved wine. According to Greek mythology, wine was invented by the god Dionysus. The art of drinking wine was centred mainly around symposium gatherings, which included philosophical and art discussions.

Greeks diluted their wine with water (or better said, their water with wine), as wine was a way to purify and improve the taste of often stagnant water sources.

How diluted was the wine? In Homer’s Odyssey, a ratio of 20 parts water to1 part wine is mentioned, but other accounts put it closer to 3–4 parts water to 1 part wine. There are also reports of adding lemon, spices, resin, or even seawater to dilute the wine. A mixture of honey and wine was also very popular.

The aim of diluting wine was to find the right balance between sobriety and drunkenness, where philosophical debates, insights, and new ideas occurred. Some of these ideas were immortalised in Plato’s The Symposium and Xenophon’s Symposium.

Resources

You can reference this text as

Jovan Kurbalija, Ancient Greek diplomacy: Politics, new tools and negotiation, ‘Diplomacy and Technology: A historical journey‘, 2021, DiploFoundation

Listen to the podcast or watch the recording of our April Masterclass Ancient Greek diplomacy: Politics, new tools, and negotiation

Recordings from all sessions are available on our YouTube channel.

[Podcast]

[Recording]

For more information on this topic, you can consult the following resources:

The Diplomacy of Ancient Greece – A Short Introduction

Author: G.R. Berridge, DiploFoundation, 2018

Employed against a warlike background, the diplomatic methods of the ancient Greeks are thought by some to have been useless but by others to have been the most advanced seen prior to modern times. This book works to its own view by looking at the conditions that produced this diplomacy, the personnel it employed, forms it took, and – in a concluding essay – its fitness for its various purposes. In passing, it draws attention to the usually overlooked private side of the diplomacy of the ancient Greeks, and the greater importance of the proxenos revealed by recent research.

Diplomacy through the ages, in Kerr P and Wiseman G, Diplomacy in a Globalizing World: Theories and Practices

Author: Cohen Raymond, Oxford University Press, 2012

This chapter presents the “big picture,” tracing the history of diplomacy from the earliest times. It shows how some of the major tools of diplomacy already existed in rudimentary form thousands of years ago, and evolved very gradually in response to changing needs. By taking the long view, we place modern-day diplomacy in perspective, suggesting that some recent “innovations” are less revolutionary than we sometimes think.

Proxeny Networks of the Ancient World (a database of proxeny networks of the Greek city-states)

Author: William Mack

Proxeny Networks of the Ancient World is a database of evidence for a particular kind of social networking between Greek city-states in the Ancient Greek world, known as proxeny (Greek: proxenia). It enables this material to be used to visualise the highly-fragmented political geography of the ancient world during the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods, and to get a sense of how densely and intensely interconnected were the states which made it up.

A Manual of Greek Antiquities

Author: P. Gardner and F. B. Jevons, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1895

Diplomacy in Ancient Greece

Author: Adcock, Sir Frank, and D. J. Mosley, Thames and Hudson: London, 1975

This in-depth study of ancient Greek diplomatic practices draws on all available sources to examine its `aims, methods, institutions and instruments’. The study, which has a chronological structure begins with the growth of Spartan power before considering relations between Athens and Sparta, the rise of Thebes, Philip of Macedon and Alexander and, finally, relations between Greece and Rome.

The Multi-State System of Ancient China

Author: Richard L. Walker, The Shoe String Press, 1953

Diplomacy in Ancient India

Author: Gandhi Jee Roy, Janaki Prakashan, 1981

Time-travel to Ancient Greece by listening to the music of the period. Here are some of the songs that may get us closer to the Ancient Greek time:

Click to show page navigation!