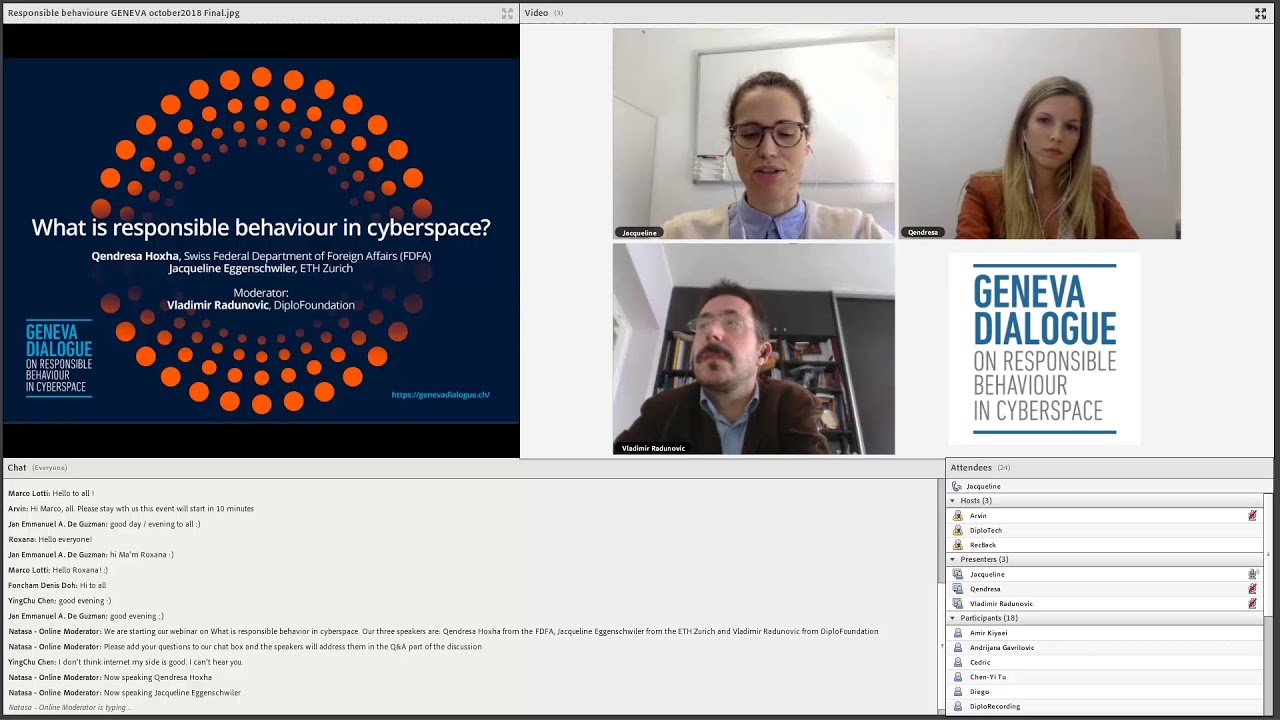

The Geneva Internet Platform (GIP) organised a webinar entitled ‘What is responsible behaviour in cyberspace?’ within the framework of the Geneva Dialogue on Responsible Behaviour in Cyberspace. The webinar explored how responsible behaviour in cyberspace is defined and how multiple stakeholders see their role in cyberspace. Joining the discussion to answer to this question were Ms Qendresa Hoxha (Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA)) and Ms Jacqueline Eggenschwiler (ETH Zurich). The webinar was moderated by Mr Vladimir Radunovic (DiploFoundation, GIP).

In his initial remarks, Radunovic pointed out that cyberspace has penetrated all parts of our life, and that it is therefore not surprising that warfare and conflicts have also moved to cyberspace, and that cyber tools are used to start conflicts. Hence, it is also not surprising that international and regional fora, such as the United Nations (UN), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) explored what the responsibilities of stakeholders in maintaining peace and security in relation to cyberspace are. Private sector initiatives have likewise tried to outline the responsibilities of states and of the private sector itself. However, work done in this regard has so far been focused on the responsibilities of states.

Geneva Dialogue on Responsible Behaviour in Cyberspace: goals and the process

Hoxha explained that the Geneva Dialogue on Responsible Behaviour in Cyberspace is an initiative launched by the FDFA in co-operation with the GIP, the UN Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), ETH Zurich, and the University of Lausanne. The Geneva Dialogue was launched because more clarity is needed in relation to the roles of all stakeholders – not just states, but also the private sector and civil society – in the use of information and communications technology (ICT) and in the context of international security. The goal of the Geneva Dialogue is to map the roles and responsibilities of these stakeholders in contributing to building stability and security in cyberspace, identify best practices for responsible behaviour in cyberspace, and put forward recommendations for overcoming potential identified gaps. The long-reaching aim of the Geneva Dialogue is to have a platform in Geneva where different stakeholders can engage in discussions on responsible behaviour in cyberspace. The Dialogue also aims to contribute to achieving a common vision of a safe, open, free, and accessible cyberspace for all.

Hoxha also spoke about the process of the project. The partners conducted intense background research in order to try to frame the discussion. They are now organising a series of webinars for interested stakeholders to share their ideas and views on responsible behaviour in cyberspace. The main event of the Dialogue in 2018 will be the expert workshop organised in Geneva, 1-2 November. A report summarising the discussions of the workshop will be finished and presented in Geneva in December 2018. There is initial discussion about continuing the Geneva Dialogue in 2019.

Radunovic clarified that three strands are working together on this project: states, the private sector, civil society and communities. Part of the work already undertaken was trying to map how these stakeholders see responsible behaviour.

Defining responsible behaviour in cyberspace

Eggenschwiler reiterated that it is challenging to define what responsible behaviour in cyberspace means, particularly if one looks beyond state behaviour and legal responsibilities of states in cyberspace. It is unclear what is expected from the private sector and civil society entities in terms of securing cyberspace or contributing to a secure and stable environment. Within the project team, the agreed definition of responsible behaviour in cyberspace is ‘behaviour by a given actor in a given set of circumstances that can be said to conform to the laws, customs and norms generally expected from that actor in those circumstances.’ This definition is vague, context-specific and context-dependant. How responsible behaviour is defined varies across different strands because of the different functions that these entities take on in society.

Radunovic also stated that there are very few specific proposals on what should be the roles and responsibilities of other stakeholders in cyberspace.

How governments see responsible behaviour

Hoxha pointed out that there is a rich body of norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviour of states in cyberspace. The existing international law sets the overall legal framework for state use of ICT in cyberspace. States must respect their obligations under customary international law, where the due diligence principle comes into place, meaning that states must do their utmost to try and stop internationally wrongful acts that emanate from their territory. States have to comply with their obligations under international humanitarian law, meaning that they must observe the principles of precaution, distinction, proportionality, necessity and humanity in their cyber operations. Human rights obligations must also be respected in cyberspace by states. Voluntary norms and principles also apply, Hoxha underlined, giving the example of 11 voluntary norms elaborated by the UN Group of Governmental Experts (UN GGE) 2015. There is also a long list of confidence-building measures (CBMs) that have been adopted by regional security organisations such as the OSCE, the Organization of American States (OAS), ASEAN Regional Forum, the African Union (AU), and, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). This framework guides the behaviour of states in cyberspace and helps build confidence between states, it defines what is possible and also outlines where the limits lie for state action and behaviour. Hoxha stressed that awareness of the existing framework must be raised, how it applies to the cyber realm must be clarified, and regional mechanisms should be made operational and implemented.

Mechanisms that the private sector and civil society use to ensure responsible behaviour

Eggenschwiler stated that there is an implicit and explicit recognition that contributions from non-state actors in norm development are required and needed. What remains unclear is in which form and across which platforms. The mechanisms that the private sector employs are concrete norm proposals, such as Microsoft’s call for a Digital Geneva Convention, and bringing together industry participants to create customary standards of what it means to behave responsibly, even if only industry-wide. The mechanisms that civil society organisations employ are primarily awareness-raising techniques, such as the issuance of special reports. Given that there is a number of secluded discussions within the realm of the UN and regional organisations, it is important that other actors do not to shy away from discussions because of the limitations in terms of access – they should engage via other fora.

International humanitarian law and cyber conflict

Audience members pointed out that not all states agreed on the application of international law in cyberspace, as they see it as the legalisation of cyber conflict.

As cybersecurity is treated in the First Committee of the UN General Assembly, it is clear that cyber is becoming a field in which states interact with each other and where conflicts may arise, Hoxha stated. However, states must respect the same rules in their cyber operations as they would in their normal military operations. Hoxha also underlined that international law must be applicable in cyberspace in times of both peace and war.

States are not agreeing how international law is applicable whether international law is applicable to cyberspace and cyber activities, Eggenschwiler noted. Therefore, the role of the private sector and civil society is to engage in norm stipulating activities, to point out unacceptable behaviour and not let malicious practices become customary practices.

Which actor is responsible for the implementation of cyber policy?

An audience member suggested that states are the only actor responsible for implementation of cyber policy. However, Hoxha mentioned the existence of studies on the difficulties in implementing the existing framework, which recognised that a lot of the infrastructure is owned by the private sector and that states do not have the means to implement the norms and measures that they created. Implementation only works with other actors, and they need to be included in policy development, she stressed. It is important for states to have a channel or mechanism of consultation with other actors, as state-led and state-centred processes would benefit from a regular and institutionalised exchange between actors.

Eggenschwiler brought up the question of an inherent responsibility for co-operation among different stakeholders, and whether this is the true responsibility that needs to be taken into account and thought about in terms of implementation.

Responsibility of the private sector and civil society regarding safe products

Audience members noted that the industry has a role in producing secure products and for informing users of potential vulnerabilities. Eggenschwiler agreed, and it is also a standard practice of good business that might affect the company’s bottom line. This is where a confluence of moral duty and business or operational duty occurs. Companies that comply with International Organization for Standardization (ISO) certification schemes or assent with ISO standards put higher thresholds for products and service provided. However, a completely secure product is impossible to create because many human and machine factors that might not be completely controllable are involved in the process. Companies should therefore focus on managing risks, rather than preventing them completely. Product liability standards may be enforced by local governments or internationally. Due diligence processes can be built upon, both on the side of companies and individual users. While the private sector should ensure that products have the highest possible level of security, users should take the necessary precautions to avoid being subjected to attacks. Civil society, academia and industry participants can contribute by shaping together an evolving regime that deals with malicious incidents.

Responsibility of the civil society to fight for values

Users of technology and devices have a civic duty to hold developers and governments accountable in terms of protecting us from malicious attacks and from potentially far-reaching destructive activities, Eggenschwiler stated. Audience members agreed that users have the responsibility to use their power to make voices heard, as citizens and as consumers.

Promoting responsible state behaviour through non-binding mechanisms

There are political and moral pressures that can be put on states in order to ensure their compliance with non-binding mechanisms, Hoxha noted. A factor that influences states’ compliance is their concern with their reputation as trustworthy and credible actors. If a norm is perceived as one that enhances national prestige, states are usually more willing to abide by it. If a norm is presented as an example of a best practice and a key actor abides by it, other states will be more willing to do so, and they will also want to belong to the group of trustworthy actors. Naming and shaming is another way to promote compliance of those that violate norms of behaviour. Confidence is built through trust and co-operation and it is vital to reducing the risk of miscalculation, conflict, misperception and misunderstanding. This can facilitate compliance with voluntary mechanisms and norms as it shapes an environment in which trust in other actors to abide to non-binding mechanisms is created.