A few days ago, Spanish authorities arrested a 35-year-old Dutchman, a few kilometres north of Barcelona. He is suspected of mounting what is being considered the biggest attack on the Internet in history.

The attack was carried out on Spamhaus, an international non-profit organisation run by volunteers, which tracks the activities of spammers and spam gangs. It maintains spam-blocking databases – along with a list of enemies – which are used by many ISPs, businesses and governments, to filter out and block spam.

|

| In this article posted on Cyberbunker’s website, the company gives its reasons for the ‘blackmail war’ with Spamhaus |

In March 2013, Spamhaus added Cyberbunker – an ISP offering hosting services for any type of content, except child pornography and terrorism-related content – to its spam blacklist. Cyberbunker, whose clients included WikiLeaks and The Pirate Bay, had long been identified by Spamhaus as hosting spam activity. It was now also being accused by Spamhaus of mounting the attack, in cooperation with criminal gangs from Eastern Europe and Russia. (It is also believed that the Dutchman is Sven Olaf Kamphuis, Cyberbunker’s ‘spokesman’).

How did this massive attack succeed (even for a short time), and what were the consequences? How real is the threat of similarly large-scale cyber-attacks, and how concerned should states and institutions be?

Our April Internet governance webinar, held last Tuesday, on The threat of cyber-attacks, was an excellent opportunity to discuss the Spamhaus attack. Our host, Diplo cybersecurity expert Vladimir Radunović, explained in detail how the attack took place, its implications, and policy aspects of cyber-attacks.

In brief, Mr Radunović explained how the Spamhaus attack took place, through what is termed a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack. A large number of computers – which could easily be our own or those of other unsuspecting users – were hijacked and malware was installed. The botnets (the group of infected computers) were then controlled by the perpetrators. The botnets were used to send (distribute) a huge amount of requests to the Spamhaus servers. This knocked their website, spamhaus.org, offline.

The attack did not stop there. The attackers amplified the attack by sending a large number of requests to DNS servers (think of ‘the Internet’s address book’), while disguising the botnets’ IP addresses with those of the Spamhaus servers, to make it appear as if the requests were originating from Spamhaus. In addition to the direct requests from botnets, therefore, the Spamhaus servers also had to deal with huge traffic sent back from DNS servers.

Knowing that reactions to their spam blacklists could possibly trigger an attack, Spamhaus engaged CloudFlare, a company which mitigates DDoS attacks. If any of its clients is attacked, CloudFlare dilutes the attack by spreading it across its facilities, using Anycast technology, and waters down the attack.

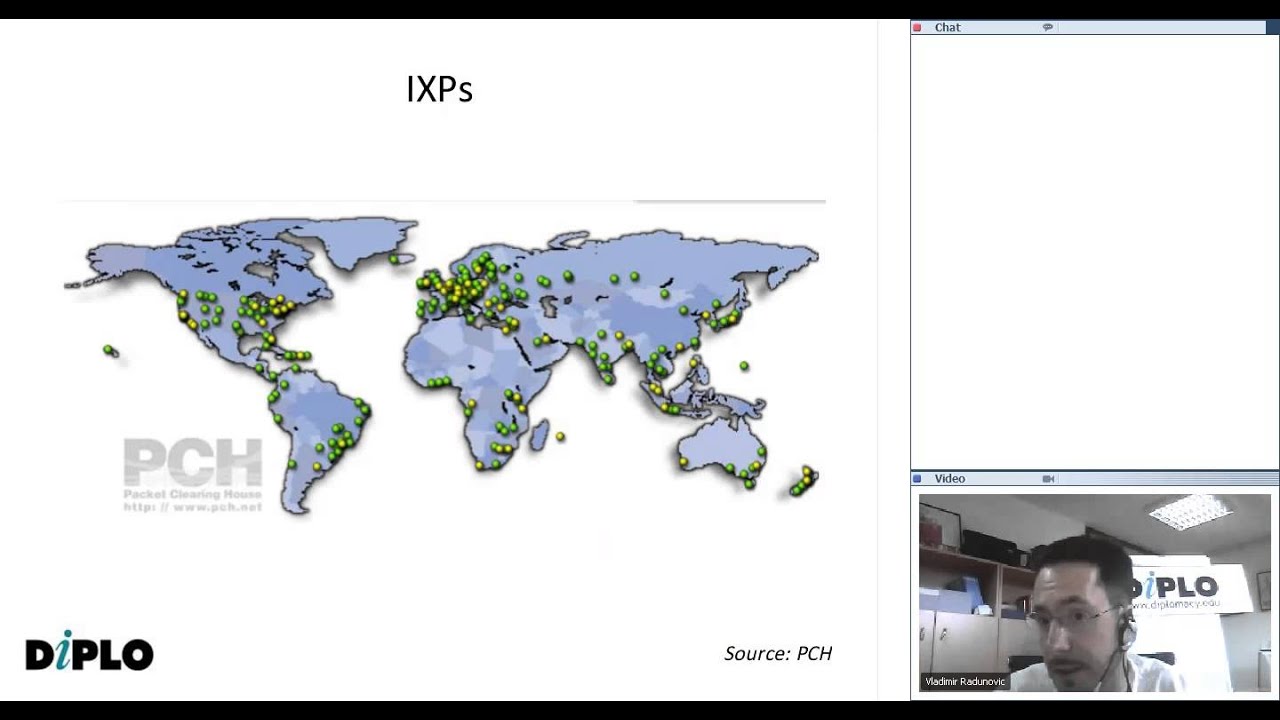

Once again, the attack did not stop there, Mr Radunović explained. The perpetrators also targeted Internet Exchange Points through which ISPs and networks exchange traffic. In this case, the perpetrators attacked CloudFlare’s bandwidth providers.

The end-result of a large-scale attack is a congested system affecting even end-users who, in military jargon, would not be considered ‘legitimate targets’. There is no doubt that the scale of cyber-attacks is increasing. Mr Radunović pointed out that there are several pressing issues and challenges that need to be tackled, including:

- The challenge of attribution, that is, identifying who is behind an attack. Mr Radunovic said that in cyberspace, it is even more complicated than in physical space, due to botnets, open resolvers and so on, making it very hard to track where an attack really originated from;

- The challenge of making distinctions: In war, there is a clear distinction between legitimate military targets and civilians; in cyberspace, the entire network is interconnected, making civilians (end-users) vulnerable to the consequences of an attack. Despite its possible legitimacy of the ends, the effects of an attack (the means) are very hard to control.

- The challenge of proportionality: in cyberspace, the principle of proportionality and non-excessive harm to civilians or property is difficult to apply, as the extent of a large-scale attack can be unknown.

Mr Radunović explained how the Spamhaus DDoS attack has all the elements of a cyber-attack, with the potential of causing disruptions beyond the specific target. In this case, the disruptions were minor, but the potential for more serious attacks is clear.

The Spamhaus attack was not unprecedented, even though it was the largest so far, of its kind. In 2007, Estonia was the target of a sophisticated cyber-attack which crippled banks, government services, and business communications. At the same time, the USA holds China responsible for continuous attacks against US companies.

Mr Radunović explained that from a political point-of-view, cyber-attacks give governments justification to control the Internet more closely. We have witnessed a strong interest in Internet control from governments during the recent WCIT meeting in Dubai, with cybersecurity being one of the main issues. Cyber-attacks support this increasing cause for concern for governments.

Discussions on the level of control needed on the Internet are analogous to a swinging pendulum: on one side, governments need to protect the Internet; on the other, this is offset by efforts to keep the Internet open. Right now, the pendulum is firmly locked on the governments’ side.

We invite you to listen to a live recording of the webinar on YouTube

in which Mr Radunović also discusses questions and comments posted by the webinar participants, including: whether it is possible to shut down the Internet through a DDoS attack; the type of attack that was used on the Iranian nuclear plants; preventive measures that can be taken by the online community, especially end-users; and many others.

You can also download the PowerPoint Presentation in PDF format, separately, here.

To receive news, announcements and follow-up e-mails regarding our IG webinars, subscribe to our IG webinars group.