Internet and social media: A focus on diplomacy

Visit the other stops on our journey:

'My God, this is the end of diplomacy!'

This was the reported reaction of former British prime minister and foreign secretary Lord Palmerston upon receiving the first telegraph message in the 1850s. More recently, in the 1990s, the US diplomat Zbigniew Brzezinski made the same prediction after using the internet for the first time.

Diplomacy survived the telephone, radio, television, and many succeeding communications technologies. Although most of these tech innovations influenced diplomacy, they did not challenge the very nature of diplomatic functions. Technology helped diplomats perform their work by offering new tools, but without altering the concept of diplomacy. In most cases, it reinforced the importance of diplomacy and defined a more important role for diplomats in society.

Today, diplomats use the internet and social media for finding and sharing information, negotiating, and communicating. Even ‘corridor diplomacy’, which was strongly linked to traditional diplomacy, has been replaced by messaging and Twitter. The internet has opened up a two-way communication channel by providing tools that allow individuals and organisations to influence global policy.

The invention of the internet

The internet started as a government project. In the late 1960s, the US government sponsored the development of the Advanced Research Projects Administration Network (ARPANET), a resilient communications resource designed to survive a nuclear attack. It was a network of computers that would enable government leaders to communicate even in the case of a nuclear attack.

In the mid-1970s, Vinton Cerf, Bob Kahn, and Louis Pouzin laid the basis for the TCP/IP (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol). The TCP/IP was a way for all computers to communicate with one another even if part of the network was disrupted.

The internet continued to evolve further, and in 1991, the British computer programmer Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web: a 'web' of information that anyone on the internet could retrieve. Berners-Lee created the internet that we know today.

Digital diplomacy | E-diplomacy

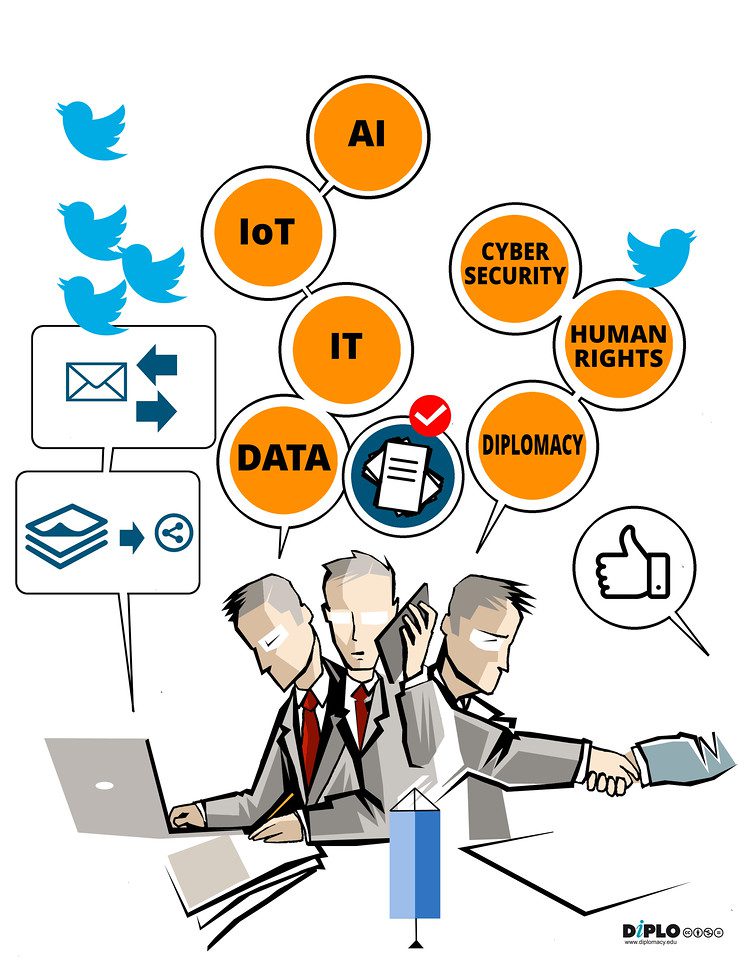

We can define digital diplomacy (e-diplomacy) as the use of the internet and social media for achieving diplomatic objectives. Digital diplomacy focuses on the changes in the environment in which diplomacy is practised, the use of internet tools for diplomatic practice, and the new topics on diplomatic agendas, such as privacy, data protection, cybersecurity, etc.

New environment for diplomatic activities

Diplomats have to deal with a changing landscape of economic and political power, and manage the fast-changing concept of state sovereignty. Future generations of diplomats will have to work in a fundamentally different geopolitical and geo-economic environment.

Diplomats have moved from having diplomatic representatives in, for example, Detroit (the economic hub of the 1950s), to those in the San Francisco Bay Area (today's economic hub). The newest model of diplomatic representation in the Bay Area is the Office of the Tech Ambassador introduced by Denmark in 2017.

Digital technology will increasingly shape the evolution of the political and economic environment for diplomatic activities.

New topics on diplomatic agendas

The internet brought new topics to diplomatic agendas. These include cybersecurity, data protection, internet governance, and artificial intelligence (AI) governance. In addition to new, digitally-driven topics, traditional topics are increasingly influenced by digitalisation. Commerce is becoming e-commerce, health is increasingly digital health, etc.

On the agenda of the United Nations and its specialised international organisations, there are more and more ‘digital’ issues. In order to reflect the emergence of new topics, countries such as Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Australia are developing digital foreign policies. The UN and international organisations are adjusting. Many others will follow in the coming years.

Internet as a tool for diplomacy

While conventional forms of diplomacy are still dominant, an increasing number of diplomats use the internet and social media as a new tool for communication, gathering information, and public diplomacy.

In the past 20 years, diplomatic tools have changed rapidly: from the introduction of the email, the use of websites by diplomatic services and international organisations, to the arrival of computers to conference rooms, and, most recently, the intensive use of social media such as Facebook and Twitter. The introduction of each new e-tool challenged the way things were traditionally done and opened up new opportunities for diplomats and diplomacy.

New tools should help diplomats perform their functions better, as outlined in Article 3 of the Vienna Convention (to represent their countries, negotiate, gather information, and protect the interests of their citizens and companies). Additionally, academic work and debates were steered towards social media and public diplomacy especially after the Arab Spring when Facebook and Twitter ‘diplomacy’ emerged.

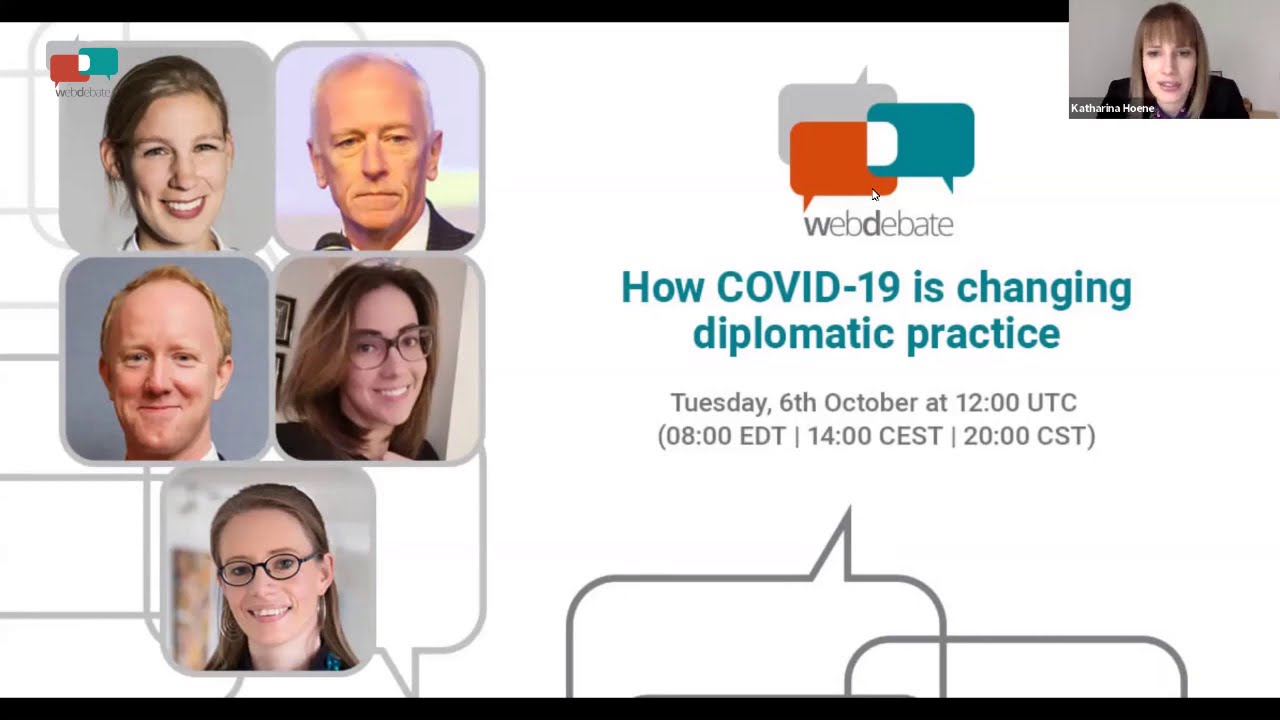

Fortunately, in recent years, more focus has been put on using digital tools for core diplomatic functions. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the seriousness of the discussions, in particular with the emergence of online meetings in multilateral diplomacy.

The use of internet and social media in diplomacy

With the expansion of social media, especially Facebook and Twitter, diplomats had to adapt and use social media as additional communications channels. Furthermore, social media proved to be an additional source of information for diplomatic reporting, particularly in environments where diplomatic and media access was limited.

In diplomatic practice, social media can be an important tool for communicating the position of negotiation parties. The dynamics of the Brexit negotiations, for example, have been shaped by the frequent tweets of chief negotiators and other actors.

Social media also enables rapid changes in public opinion. Therefore, diplomats must recognise the signals at an early stage and take them very seriously.

According to the latest numbers, Twitter has close to 400 million users. As users rush to their Twitter feeds for the latest news and statements, diplomats have to be prepared. The once marginal activity of diplomats has become almost a central practice of state diplomacy.

According to Twiplomacy (which provides studies on the use of digital tools by governments and international organisations), in 2018, over 97% of all 193 UN member states had an official presence on Twitter.

The most popular platform globally for world leaders is Twitter, followed by Facebook, and then Instagram.

Until the 2020 US elections, former US president Donald Trump's personal Twitter account (@realDonaldTrump) was the most followed account with 81.8 million followers. Trump' was followed by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Pope Francis. The Pope has over 50 million followers across his nine @Pontifex accounts in multiple languages.

The UN also uses social media platforms and other digital tools to enhance the outreach of its messages. Due to COVID-19, the World Health Organization (WHO) dramatically increased its followers to 21 million on all social media platforms, almost catching up to the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the UN.

In 2019, Twiplomacy organised a twitter poll. They had asked world leaders, governments, and foreign ministries on Twitter how they used the platform and what were the benefits of Twitter for digital diplomacy. Most foreign ministries replied that Twitter is a tool for furthering diplomatic and foreign policy goals, and communicating diplomatic and consular activity. One user wrote that the great benefit of Twitter for diplomacy is that content travels far and fast, directly engaging and impacting people.

Online conferencing and e-participation

COVID-19 has shifted diplomacy online to conferencing platforms such as Zoom. However, online meetings are not as new as one might think. The first remote participation session in multilateral diplomacy was held by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in 1963.

The availability of the internet in conference rooms has made remote participation a reality for more inclusive and open international negotiations.

In light of COVID-19 social distancing and lockdowns, diplomatic practice had to adapt. Overall, diplomacy has proven remarkably resilient. Videoconferencing and other means of digital communications have ensured the continuity of diplomatic practice and negotiations.

Yet, the absence of informal spaces for meetings is regarded as a real loss in terms of relationship-building and information gathering. In addition, some protocol requirements do not translate well into online meetings and videoconferencing. In face-to-face meetings, the rank and status of participants is highlighted through arranged seating. However, this type of hierarchy signalling cannot be established as clearly during videoconferencing on standard platforms.

As diplomatic practice has shifted towards videoconferencing, key challenges include solving security issues, adapting to changes in communications and negotiation dynamics, offering translation services, and ensuring a stable internet connection. There are concerns about the danger of exclusion due to bandwidth requirements and security restrictions. This is a particular challenge faced by small and developing countries.

Hybrid (blended) forms of diplomacy that combine in-situ and virtual attendance at meetings have emerged as another adaptation. Given the advantages, this form of hybrid diplomacy is here to stay. Diplomatic practice has always been an interplay between continuity and change, and the present moment is a crucial turning point which might determine the future of diplomatic practice.

Meanwhile in… Space

Diplomacy isn’t just terrestrial anymore. Since the days when the first satellite was launched into space, diplomats had to consider the events occurring in the Earth’s orbit, on the surface of the Moon, and now even on Mars.

At the beginning of the space age, nations were worried about sending nuclear weapons into orbit and most of the effort was invested into promoting the peaceful use of outer space. The landmark agreement, the Outer Space Treaty, was reached in 1967. It stated that space should only be used for peaceful purposes, and that neither space nor celestial bodies can become the sovereign territory of any nation.

Also of importance is the so-called Moon Agreement of 1979, a multilateral treaty regulating the activities on Earth’s only natural satellite, but it was not signed by the USA, USSR/Russia, nor China.

The recent increase in the number of countries and private companies using low Earth orbit (LEO), and our growing dependence on satellites is increasing the need to negotiate about rights and obligations. There are now more than 3,000 satellites. Experts predict that in ten years, this number will rise to over 100,000. Not to mention space debris.

Space is becoming more commercial and more militarised. Even without a new weapons race in orbit, or satellite jamming, or destruction, more congestion in space means more potential misunderstandings.

The Cold War international law on space is out of date and new codes of conduct are needed, codes that would oblige states, companies, and individuals to act responsibly in space. The largest law gaps have to do with the potential commercial use of space. Currently, it is the USA that is shaping space law and this is why China, Russia, and India are not following. Excluded from the International Space Station for its secretive conduct, China is now planning to build its own permanent space station.

Cheers! Coffee

Coffee is the world's third most consumed beverage (after water and tea) and the most traded commodity on stock exchanges after petroleum. We drink around 500 billion cups every day!

Coffee shrubs grow in the mountains of Ethiopia. Aware of their effects on the body and mind, the locals first chewed them. Later they brewed them raw, making a drink similar to tea. It was only in the 15th century that people started to roast and grind beans before brewing them. The first accounts of cultivation came from Yemen and Arabia in the mid-1400s. It was spread further by Sufis, Islamic mystics, who drank it as a holy ceremonial drink.

Coffee drinking led to the establishment of coffee houses. In 17th and 18th century Europe, it was the preferred drink of intellectuals who thought that it opens their minds without the side effects of alcohol. Coffee houses were the place to find out all the latest news, gossip, and meet new people.

Coffee beans were often given as a diplomatic gift. In 1714, after the Utrecht peace treaty between the Netherlands and France was signed, the mayor of Amsterdam presented a coffee plant to King Louis XIV of France

In the late 18th century, about half of the world's coffee came from the former French colony Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti), and the poor conditions in which the black slaves worked on plantations led to an uprising and the forming of the first independent state created by slaves. After the 1773 Boston Tea Party during the American Revolution, it was a patriotic duty to drink coffee instead of 'British tea'.

In the early 20th century, 95% of the world's coffee was produced in Latin and South America, and a lot of it was drunk in the USA. Its prices very soon became a political question: if prices went up, consumers would be unhappy; if prices went down, that could spark revolutions in producing states. This led to the 1962 International Coffee Agreement that set limits on exports and imports as well as quotas for countries.

Watch the recording of our November Masterclass #Diplomacy: Internet and social media. Consult the PPT presentation.

Recordings from all sessions are available on our YouTube channel.

[Recording]

Diplomacy between tradition and innovation

As part of the series, Dr Kurbalija talked with Ambassador Stefano Baldi about the interplay between technology and diplomacy, continuity and change, tradition and innovation. Ambassador shared his reflections on the 30 years of intensive digital and internet developments, and gave some practical advice to the new generations of diplomats.

Ambassador Stefano Baldi is a career diplomat in the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

As of 2021, he serves as an Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the OSCE in Vienna. He was Ambassador of Italy to Bulgaria from 2016 to 2020 and previously Training Director at the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affair and International Cooperation from 2011 to 2016. He was Head of the Science and Technology Cooperation Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 2010 to 2011.

From 2006 to 2010 he was First Counsellor at the Permanent Mission of Italy to the European Union, responsible for legal and financial aspects of the Common Foreign and Security Policy as Relex Counsellor.

He has also served at the Permanent Mission of Italy to the International Organizations in Geneva and to the Permanent Mission of Italy to the United Nations in New York in charge for disarmament affairs. He has been the first head of the Statistical Office of the Ministry from 2000 to 2002.

He has lectured in with many Italian universities (Roma La Sapienza, LUISS, Roma TRE, LUMSA, Trento, Pavia, Firenze), holding seminars and courses in international affairs, particularly in multilateral diplomacy.

His most recent researches focus on diplomatic management, Social media for International Affairs and Books written by diplomats. He is author and editor of more than 30 books. His recent publications include several books on the activities of diplomats (Diplomatici, 2018) and a book on Management for diplomats (Manuale di management per diplomatici, 2016). He has also published, both in Italian and in English, the results of a comprehensive research on books written by Italian Diplomats (Through the Diplomatic Looking Glass, Diplo, 2007). His most recent books concern a photographic research on Italian Diplomatic History.

Browse through the list of videos related to the impact of the internet and social media on diplomacy:

For more information on this topic, you can consult the following resources:

Information technology and diplomacy in a changing environment (Discussion papers)

Author: Jovan Kurbalija, 1996, Center for the Study of Diplomacy, Diplomatic Studies Programme

In this paper Jovan Kurbalija analyses the impact of Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) on diplomacy.

Internet Guide for Diplomats

Authors: Jovan Kurbalija, Stefano Baldi, 2000, DiploProjects

The Internet Guide for Diplomats is the first guide specifically conceived and realised to assist diplomats and others involved in international affairs to use the Internet in their work. The book includes both basic technical information about the Internet and specific issues related to the use of the Internet in diplomacy. Examples and illustrations address many common questions including web-management for diplomatic services, knowledge management and distance learning.

Twitter for Diplomats

Author: Andreas Sandre, 2013, DiploFoundation

Twitter for Diplomats is not a manual, or a list of what to do or not to do. It is rather a collection of information, anecdotes, and experiences. It recounts a few episodes involving foreign ministers and ambassadors, as well as their ways of interacting with the tool and exploring its great potential. It wants to inspire ambassadors and diplomats to open and nurture their accounts – and it wants to inspire all of us to use Twitter to also listen and open our minds.

Social Media Influence on Diplomatic Negotiation: Shifting the Shape of the Table

Authors: Cathryn Clüver Ashbrook, Alvaro Renedo Zalba, 2021, Negotiation Journal, Volume 37, Issue 1

Social media is changing not only the atmosphere in which international negotiations take place; it is also changing the very substance of the deals. Because of the pace and proliferation of social media, negotiators must read “weak signals” early on—and anticipate a quickly organized, highly motivated opposition. However, diplomatic negotiators still lack the tools to engage in this sort of anticipatory strategy design. This article examines two recent cases, one involving the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership and the other involving a German Constitutional Court’s ruling on the European Central Bank’s Public Debt Purchasing Program, in which social media had a highly disruptive, unanticipated impact on international negotiations—to the point of forcing negotiators’ hands—and suggests institutional remedies to better anticipate the catalytic impact of advancing technology on diplomatic interactions.