If ever there was a time for governments to get their communications right, it is now. Governments everywhere are under scrutiny for what they say, how accurately they report facts, and what actions they are proposing. COVID-19 is spreading faster than press offices can get their messages out. Thanks to the Internet, the media and members of the public are posting stories which may not show governments in their best light. People need to know will they get sick, will they receive the treatments they need, and will they lose their jobs, their homes, their lives. What they are getting instead are mixed messages.

Governments are taking different approaches – serious lockdowns in Italy vs. business as usual in Sweden; all borders closed in Peru vs. an economy-ahead-of-quarantine approach in Brazil; wholescale testing in South Korea vs. travellers entering the UK from virus hotspots without so much as a swab or temperature check. There is little sign that governments are working collectively or consistently. Advice from the World Health Organization (WHO) secretary general is not heeded. Instead, we hear of front-line health workers in wealthy, developed countries still functioning without access to adequate protective clothing.

We see footage of people sprayed with toxic detergent or beaten in the street because they are desperately looking for food for their families.

We hear of emergency measures in Hungary which amount to the discarding of the democracy it fought to reinstate after 1989. These are images that will not easily be forgotten once the pandemic is over and countries try to repair their damaged reputation.

Meanwhile, the myths continue to circulate on social media that the pandemic is a hoax, or just another flu, or that it can be cured by sunlight or sips of warm water. Why are people so ready to believe fake news? Does it reflect a basic mistrust of official messages, as Hugo Mercier of the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) suggested? What can governments do to restore this possible loss of faith in officialdom?

Public diplomacy is at the forefront of no one’s mind at the moment, but states will be judged in the future for their behaviour towards their own citizens and to one another, so perhaps the first step at this time of crisis is for states to stop the tit-for-tat blame-laying, to stop playing the propaganda game, and to seize the opportunity for collective action and making use of the new technologies available to us.

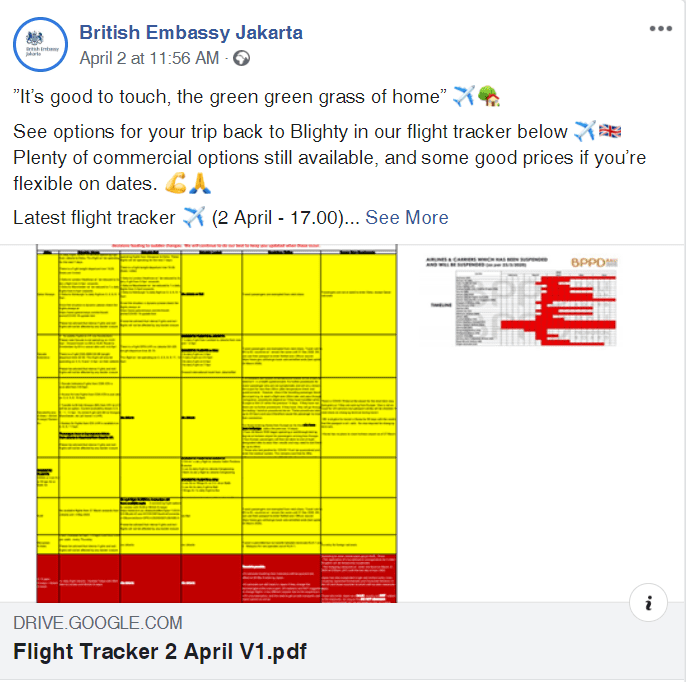

Twenty years ago, it would have been unimaginable to hold international conferences remotely. Hourly updates on support available for citizens stranded in foreign countries would have been impossible without Facebook.

Data on the spread of the virus and exchanges of what measures have proved effective would have taken days to compile and share. This crisis has forced the international community to adopt new ways of working, new methods of meeting, and new forms of communications. The technology has been around for a while. Other sectors of society have already undergone their digital transformation. In diplomacy, many governments have only slowly embraced the new tools and working practices, perhaps because of IT infrastructure difficulties, perhaps because of nervousness about confidentiality, while some remain reluctant to set aside the diplomatic protocols and rules of procedure appropriate for a non-digital era. This is the ideal opportunity for diplomatic services to change their mindset and find novel ways of collaborative working.

Without meeting up physically, 53 countries have signed up to the United Nations secretary general’s appeal on 23 March, backed by the Pope, for a global ceasefire. States that haven’t yet done so should join up, preferably without the same old tired ’It’s not us, it’s them’ defence. States could meet remotely to discuss packages of support for developing countries whose economies have almost completely shut down because of lockdowns elsewhere or for the hundreds of thousands of refugees and displaced persons who have no options for social distancing or protecting themselves. And states could collectively review ways of countering fake news and of maximising outreach to people who haven’t yet got the message that preventative measures apply equally to everyone, using whatever digital tools are appropriate.

This pandemic will pass in time, but our societies will have changed. Our diplomatic services need to change alongside them. How governments perform now in managing the pandemic internationally, working together instead of against each other, will shape future public perceptions at home and elsewhere of their competence, their honesty, and their dependability. And how they perform in future crises will depend on how well they have observed the lessons from this one.

Ms Liz Galvez was a senior diplomat with the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, taking early retirement in 2006 with the rank of counsellor. She has been teaching for DiploFoundation since 2009, providing training in public diplomacy and multilateral negotiating skills, and co-lecturing the courses E-Diplomacy and Public Diplomacy in which she discusses public diplomacy with focus on social media.