In the brightly lit aisles of a Sephora in Paris or a Target in Ohio, among the legacy brands of France and the United States, a new kind of aesthetic authority has taken hold. It announces itself not with bold proclamations but with the pastel packaging of serums, the whimsical design of animal-faced sheet masks, and the scientific promise of ingredients like snail mucin and fermented rice water. In the old calculus of international relations, where a nation’s standing was tallied in warships and trade surpluses, a new and altogether more luminous currency has entered the exchange. For the Republic of Korea, a country that spent the latter half of the twentieth century in a determined sprint toward industrial modernity, a period known as the “Miracle on the Han River“, one of its most potent instruments of global persuasion is not a semiconductor or a supertanker but something far more intimate: the promise of a flawless complexion. The global ascent of K-beauty has become a quiet but formidable pillar of the Hallyu, or Korean Wave, representing a masterstroke of diplomatic charm.

The soft power of skincare

That a nation might project power through its cosmetics is a distinctly twenty-first-century notion, a manifestation of what the political scientist Joseph Nye famously termed “soft power“, a concept involving the ability to attract and co-opt rather than coerce. This is cultural statecraft conducted at the bathroom mirror, an arena where the adoption of another country’s rituals nurtures an affinity that is both deeply personal and quietly pervasive. When a consumer in Paris or São Paulo commits to a ten-step skincare regimen, an act of diligence that can feel almost meditative, they are not merely purchasing a product; they are subscribing to a cultural practice. This transaction, repeated millions of times a day worldwide, helps to recast South Korea’s national image. It works to soften the harder edges of its twentieth-century story, a fraught geopolitics defined by the DMZ, a famously demanding corporate culture of chaebols, into an aesthetic that feels innovative, sophisticated, and, above all, aspirational. The nation of gritty resilience is now also the nation of the coveted “glass skin” glow, an image far more alluring than that of a heavily fortified border.

Prevention, not camouflage

The success of K-beauty is hardly an accident; it is the result of a quiet philosophical coup, executed over decades. Where the Western cosmetics industry has historically emphasised camouflage and correction, a foundation to cover, a concealer to hide, a harsh astringent to zap a blemish, the Korean approach is one of cultivation and prevention. It champions a ‘skin-first’ ideology, which posits that true beauty is achieved not through artifice but through the diligent, long-term pursuit of healthy, luminous skin. This creed has been brought to life by an engine of ceaseless innovation, born of a hyper-competitive domestic market where consumers are famously knowledgeable and demanding. This intense local pressure, a kind of aesthetic Darwinism, forces companies into a blistering cycle of research and development. The government, for its part, has not been a passive observer; it has actively supported the industry as a key export sector. Concepts that once seemed exotic, such as the cushion compact (an ingenious fusion of liquid foundation and a portable sponge), the pimple patch (a discreet hydrocolloid dressing), and the sleeping mask (a deeply hydrating overnight treatment), have migrated from the far corners of the Internet to the mainstream cosmetic counter. This is not folk wisdom, but advanced science, with companies investing heavily in dermatological research to stabilise novel ingredients, such as centella asiatica and propolis, and perfect their delivery into the skin.

Beauty diplomacy in action

What one sees on the global stage, the proliferation of Korean cosmetics in the chic department stores of Paris and the brightly-lit aisles of American drugstores, is not only the flourishing of an industry, but something more similar to a state-choreographed ballet. Behind the curtain, the South Korean government and its affiliated bodies, such as the industrious Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA), are not simply cheerleaders; they are the logistical architects and financial underwriters of this expansion. This is beauty diplomacy, a deliberate policy that harnesses the almost primal allure of cosmetics as an instrument of statecraft. The state’s hand is visible, if one knows where to look: in the subsidies that allow smaller, innovative brands to erect dazzling pavilions at international trade fairs, in the painstaking streamlining of export regulations that once felt like Gordian knots, and in the official designation of these products as cultural emissaries.

The calculus here extends far beyond the balance sheet, into the more nebulous, yet arguably more valuable, ledger of international goodwill. It is fundamentally about building relationships. Consider the discreet exchange in a foreign capital: a visiting dignitary is presented not with a customary pen or plaque, but with an immaculately packaged gift set of luxury Korean skincare. The gesture itself, intimate, concerned with personal well-being, is a disarming overture. This same gentle persuasion operates on a grander scale when a K-beauty exhibition opens in a new market, generating a public enthusiasm that formal diplomatic channels can rarely muster. It is, in essence, a charm offensive waged with essences and emulsions, a soft-power campaign fought not with stern communiqués but with the subtle allure of sheet masks and sleeping packs. By softening the ground in this way, by creating a warm and receptive public impression, these silent ambassadors in their jewel-like jars help pave the way for deeper, more consequential collaborations in technology and trade. It suggests, with a quiet confidence, that a nation’s global appeal can be cultivated with the same meticulous patience and artful layering as a flawless complexion.

The hallyu feedback loop

This aesthetic export, of course, rarely travels alone. It is woven, inextricably, into the fabric of the Korean Wave, creating a powerful cultural ecosystem where each element reinforces the others. A viewer, deeply immersed in a globally popular Netflix K-drama like Crash Landing on You, finds herself mesmerised by the impossibly dewy skin of the lead actress, Son Ye-jin, and soon discovers that the actress is a brand ambassador for a line of ampoules and creams. A K-pop devotee, streaming the latest music video from Blackpink, aspires to replicate the members’ immaculate complexions and learns they represent a Korean beauty brand. These television shows and musical acts are, in effect, global showcases, turning a particular shade of lipstick or a specific brand of essence into an international best-seller overnight. The synergy is amplified by a digital sphere of YouTube tutorials and TikTok trends, where international influencers act as cultural translators, demystifying the ten-step routine for a global audience. For many, a three-dollar Korean face mask is the initial point of entry into a sprawling cultural universe. The curiosity sparked by a skincare product can easily blossom into an appreciation for the films of Bong Joon-ho, a taste for the music of BTS, or even an inclination to learn the Korean language on Duolingo. All aspects of the Hallyu wave, movies, music, food, and beauty products, coalesce to create a comprehensive and highly appealing cultural experience.

From industrial grit to cultural glow

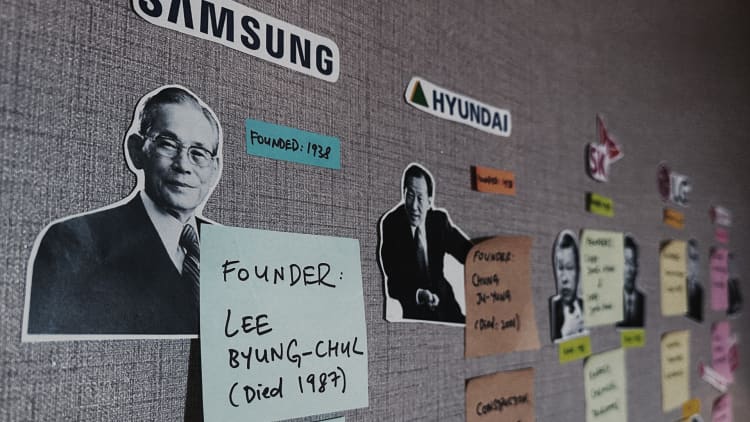

Ultimately, the global fascination with K-beauty has burnished South Korea’s national brand. It has helped the country complete its transition from a gritty industrial powerhouse, synonymous with Samsung and Hyundai, to a global arbiter of taste and a wellspring of cultural innovation. If the “Miracle on the Han River” was the nation’s first act, built on hardware and sheer will, then the Hallyu is its second, a more subtle triumph built on software and style. The image now projected is one of youthfulness, meticulousness, and forward-thinking creativity, an identity with tangible consequences. It inspires a robust tourist trade, with devotees flocking to Seoul’s Myeong-dong district on what they call “K-beauty pilgrimages” to haul back suitcases of products. It elevates the cachet of the “Made in Korea” label across all sectors, creating a halo effect for everything from fashion to technology. In this way, the quiet, persistent campaign for a healthier glow reveals itself to be a surprisingly potent form of modern statecraft. It is perhaps proof that the path to global influence need not always be paved with military might or economic leverage, but can sometimes be found in something as universal and intimate as the pursuit of radiant skin.

Click to show page navigation!