[Webinar summary] Decrypting the WannaCry ransomware: Why is it happening and (how) is it going to end?

Author: Andrijana Gavrilović

The WannaCry ransomware cyber-attack shook the whole world. The attack affected many countries, with victims ranging from health clinics and government institutions, to schools and businesses.

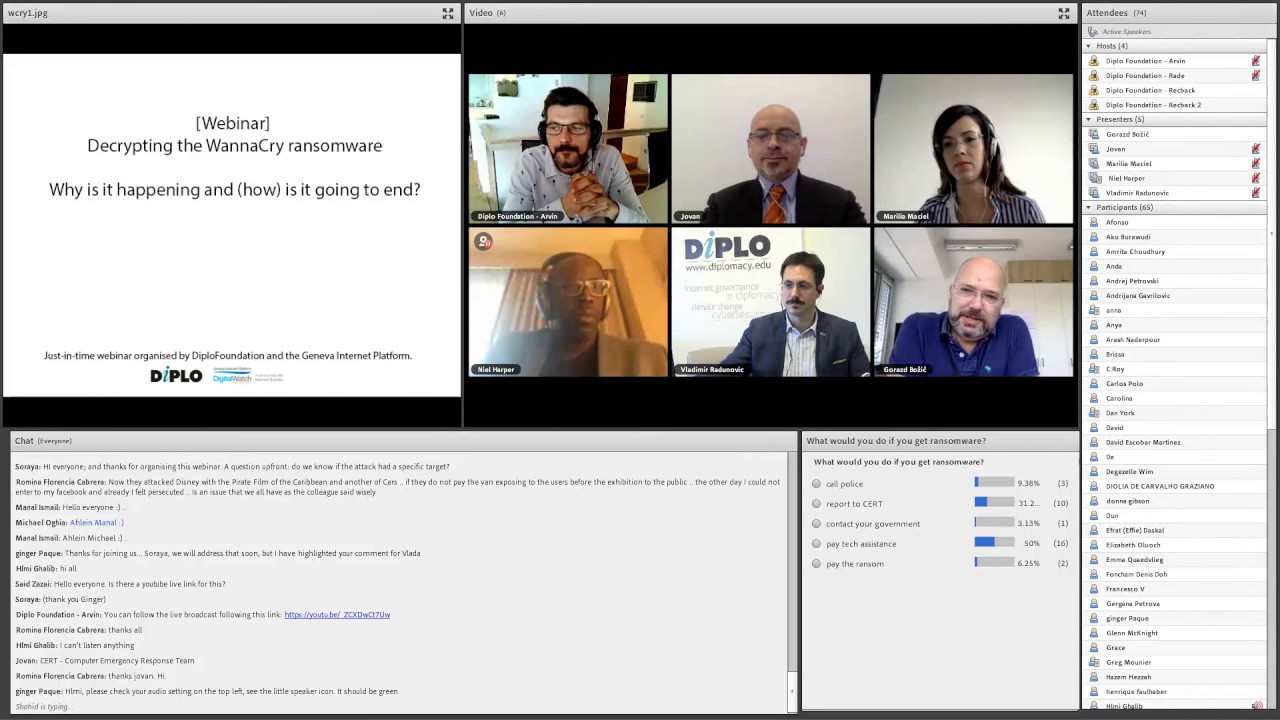

In a just-in-time webinar organised by DiploFoundation and the Geneva Internet Platform, experts from different fields shed light on the policy implications, including the technical, legal, diplomatic, and economic aspects. The discussion, held online on Thursday, 18th May, was divided into four stages: reaction, assessment, reflection, and prevention.

Experts included: Dr Jovan Kurbalija, Director of DiploFoundation and Head of the Geneva Internet Platform; Ms Marilia Maciel, DiploFoundation’s Digital Policy Senior Researcher; Mr Neil Harper from the Internet Society; Mr Arvin Kamberi, DiploFoundation’s Researcher and Multimedia Coordinator; Mr Gorazd Bozic, Head of the Slovenian National Computer Emergency Response Team (SI-CERT) and board member of ENISA. The moderator was Mr Vladimir Radunovic, Director of E-diplomacy and Cybersecurity at DiploFoundation.

Reacting to the attack

When an attack occurs, whom should we call? Is there a single hotline or phone number to dial? Should we call the police, report the attack to CERT, contact the government, pay for technical assistance, or, should we pay the ransom?

Bozic said that the response to ransomware varies from country to country. What it depends on is the situation in the country – whether a CERT exists, what kind of services it provides, whether the CERT is available to the public and enterprises, and what that the role of the police is. In most cases, it is good to contact the CERT first, since it may have information about the outbreak in question. What the CERT can do is to give advice on how to try and restore the data, it can give information and feedback about other infected systems – whether they paid the ransom, and if they did, whether they received an encryption key after payment; it can also advise on how to prevent such an attack from taking place again. Bozic said that having no back-up of the files on the infected computer would limit the options to paying the ransom. He also claims that if no one paid the ransom, this business model would die out, yet it is understandable why victims do pay.

Harper pointed out that there is a number of options for businesses, especially if they have established an ‘accident response procedure’, such as disconnecting the infected device from the network. This way, the bug track or vulnerabilities can be looked at, and then the business can disconnect their Outlook or their exchange server to stop the ransomware from self reciprocating. This way it is isolated and the victim can decide on the next steps to take. Harper stressed that contacting the national CERT is very important as the CERT will disseminate the information to other stakeholders, who will be prepared to respond to the ransomware. He also advised having strong back-up solutions because they can help the victim respond; copying data onto a cloud is not enough and encrypting the back-up is crucial!

Reflecting on the attack

Who is at fault? Can blame be assigned to the NSA, Microsoft, CEO-levels, IT departments or the end users?

Maciel considers assigning blame to be the wrong approach, as this is a shared responsibility – the best way to curb ransomware and other malware is to work together. The responsibility of individuals is to have their antivirus programs updated and their data backed-up. The responsibility of governments is to have their own systems updated and participate in procedures that the technical community puts in place. CERTs have a role to play, and so do the companies. Maciel pointed out that the companies need to take responsibility for their products. In this particular case, Microsoft reacted proactively, issuing a patch for the vulnerability, EternalBlue, as soon as they heard of it. The affected users did not install the patch for many reasons – some have older versions of Microsoft Windows which are hard to update; in many cases Microsoft itself stopped offering support for older versions of Windows; some users use pirated versions of the operating system; and some have issues due to geopolitical reasons – for example the citizens of Cuba, due to the UN’s blocking. Maciel once again underlined the responsibility companies have for their products, as a very common approach is patch and pray – putting their product on the market before the competitors do, before it is tested and safe.

Kurbalija said that we must be realistic about what governments can do in order to provide security for their citizens in cybersprace. Most governments do not have the tools and means to protect their citizens online, given that the Internet’s infrastructure is based on anonymity and decentralised organisation. The tools the military, the police, and border control had in the past, are very often beyond their reach when it comes to the cyber world. Therefore, Kurbalija believes that governments should be given the benefit of the doubt.

Harper highlighted the trend of governments developing offensive cyber capabilities, and a report indicates that 60 of them are doing so. However, this is not the right approach in terms of maintaining online trust. Governments are not working together and collaborating to stop cyber-attacks. The private sector should carry some of the responsibility, thinks Harper, but small and medium enterprises often do not have enough resources to update their systems – vulnerability management and patch management are resource-intensive processes. A lot of businesses are reluctant to deploy a patch in case it malfunctions, since this can hurt their service to customers and their reputation. He finished by pointing out that there are still critical systems which use Windows XP and Windows 95 and cannot be updated, which means a possible national security issue and potential loss of life.

Bozic picked up where Harper left off and pointed out that companies are pressured not to develop their own operating systems. Also, since no one is willing to pay a higher price for a secure system, consumer operating systems are used – until something cracks. Then blame gets assigned. Bozic stressed that the NSA can be blamed for WannaCry, but there was other ransomware that the NSA had nothing to do with. However, if governments are to blame, one of the solutions they can implement to end all ransomware is banning Bitcoin. The ransom is being paid in Bitcoin because money transfers can be anonymised; thus Bitcoin is an enabler of this business model. Answering a question from the audience, Bozic commented that the reason a kill-switch was put in WannaCry is still unknown. One of, and the most likely solution, is that WannaCry was a development version that escaped from the development environment and the kill-switch was there for development purposes.

Assessing the damage

How much did the attack cost and what was Bitcoin’s role?

Kamberi said that Bitcoin is a public ledger, in which everything is transparent and where every account can be tracked. The three accounts into which ransomware money is deposited can be constantly monitored from the blockchain. So far, approximately 50 bitcoins, or just over USD$ 105 000, were paid in ransom. Compared to other ransomware, this is not a large sum. For now, no one has accessed these wallets, and Kamberi is doubtful anyone will, since all eyes are on them. Bitcoin as a ledger is anonymous, but not completely anonymous. The ledger itself can be encrypted and privately protected, but the devices that actually interact with the wallets can be traced, especially by forces such as the NSA, Interpol, etc. Kamberi said that in order to access the money, the perpetrators of the attack would have had to be prepared to do so before the attack itself, which would have required a lot of resources and a lot of patience. Kamberi pointed out that there are much darker digital currencies than Bitcoin, like Darkcoin and Monero, which specialise in anonymising on the Internet. He concluded by naming other currencies, like the dollar, which are also used to pay ransom, and stressed that banning Bitcoin is not the solution. Banning Bitcoin would be like banning encryption.

Who is behind the attack? A group of experienced criminals, a group of inexperienced criminals, a government, the security industry?

Bozic said that there is not enough information to claim to know who is behind this attack. It seems like it is the work of copycats, inexperienced criminals. The speed at which it spread was working against it, and there were many malfunctions in this ransomware. Bozic pointed out that the largest number of attacks occurred within the Russian Federation, which is where WannaCry differentiates from other ransomware. Other ransomware does not encrypt the data of Russian citizens since the perpetrators avoid being chased by FSB, the Russian security service. This is why conspiracy theorists may believe that the NSA is behind the attack. However, Bozic reiterated that we do not know who is responsible.

The role of Digital Geneva Convention

Kurbalija believes that Microsoft’s proposal is a good, timely proposal which opens some important questions. It starts a discussion in one of the most tested international legal regimes – the Geneva Conventions and the international humanitarian law. However, Kurbalija said that had the Digital Geneva Convention been in effect, it would not have stopped WannaCry. As far as the future goes, the Digital Geneva Convention would not make prohibited behaviour impossible. The issues are much deeper, related to the architecture of the Internet. What the Convention could do is to raise the costs for perpetrators and increase the chance of identifying them, improve coordination between governments and other players. Kurbalija concluded that this proposed Convention opens up an interesting discussion on the possible tools and means to coordinate global action in the cybersecurity field.

Maciel thinks that governments should not make the situation worse by curbing encryption and putting limitations on it. If encryption is made weaker, it is weaker for both the criminals and the users. She also highlighted that exploiting vulnerabilities and zero days is not a way to make everyone safe. Maciel believes that governments should adopt basic product regulations that companies should follow when they put a product out. Another thing governments can do is to create mandatory ways for companies to report data leakage and cyber-episodes. Maciel concluded by highlighting that more co-operation between governments is needed.

Harper agreed that there is a number of stakeholders who hold responsibility for the protection from cyber-attacks. It is a collective responsibility which emphasises collaboration and co-operation. The collaboration can occur at an international level, in an organisation, or on a national level – where the government acts as a convener for a cybersecurity strategy that will incorporate various stakeholders.

Learn more about the attack: visit the dedicated space on the Digital Watch observatory. Join us for our next monthly briefing on Tuesday, 30th May, for a follow-up to the discussion, and read additional analysis in May’s newsletter, out 31 May.