A New Agenda for Peace | Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 9

Introduction

CHAPEAU

The challenges that we face can be addressed only through stronger international cooperation. The Summit of the Future, in 2024, is an opportunity to agree on multilateral solutions for a better tomorrow, strengthening global governance for both present and future generations (General Assembly resolution 76/307). In my capacity as Secretary-General, I have been invited to provide inputs to the preparations for the Summit in the form of action-oriented recommendations, building on the proposals contained in my report entitled “Our Common Agenda” (A/75/982), which was itself a response to the declaration on the commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the United Nations (Assembly resolution 75/1). The present policy brief is one such input.

PURPOSE OF THIS POLICY BRIEF

In the declaration on the commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the United Nations, heads of State and Government undertook to promote peace and prevent conflicts. Honouring this pledge will require major changes by Member States, in their own actions and in their commitment to uphold and strengthen the multilateral system as the only viable means to address an interlocking set of global threats and deliver on the promises of the Charter of the United Nations around the world.

Member States must provide a response to the deep sense of unease which has grown among nations and people that Governments and international organizations are failing to deliver for them. For millions of people, the sources of that disappointment are to be found in the horrors of hunger, displacement and violence. Inequalities and injustices, within and among nations, are giving rise to new grievances. They have sown distrust in the potential of multilateral solutions to improve lives and have amplified calls for new forms of isolationism. As the planet warms, marginalization grows and conflicts rage, young people everywhere have grown disillusioned at the prospects for their future.

The choice before us is clear. Unless the benefits of international cooperation become more tangible and equitable, and unless States can manage their competition and move beyond their current divisions to find pragmatic solutions to global problems, human suffering will worsen. The urgency of all countries to come together, to fulfil the promise of the nations united, has rarely been greater.1Declaration on the commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the United Nations, para. 1.

My report on Our Common Agenda offered a vision to deliver on this promise. It outlined a multilateral system that could be more just, networked and effective. Building this new multilateralism must start with action for peace, not only because war undermines progress across all our other agendas, but because it was the pursuit of peace that in 1945 unified States around the need for global governance and international organization.

This new multilateralism must recognize that the world order is shifting. It must adjust to a more fragmented geopolitical landscape. It must respond to the emergence of new potential conflict domains. It must also rise to address myriad global threats that have locked States into interdependence, whether they desire so or not. This new multilateralism demands that we look beyond our narrow security interests. The peace that we envisage can be pursued only alongside sustainable development and human rights.

The collective security system that the United Nations embodies has recorded remarkable accomplishments. It has succeeded in preventing a new global conflagration. International cooperation – spanning from sustainable development, disarmament, human rights and women’s empowerment to counter-terrorism and the protection of the environment – has made humanity safer and more prosperous. Peacemaking and peace- keeping have helped to end wars and prevent numerous crises from escalating into full-blown violence. Where wars broke out, collective action by the United Nations often helped shorten their duration and alleviate their worst effects.

Nonetheless, peace remains an elusive promise for many around the world. Conflicts continue to wreak destruction, while their causes have become more complex and difficult to resolve. This may make the pursuit of peace appear a hopeless undertaking. However, in reality, it is the political decisions and actions of human beings that can either sustain or crush hopes for peace. War is always a choice: to resort to arms instead of dialogue, coercion instead of negotiation, imposition instead of persuasion. Therein lies our greatest prospect, for if war is a choice, peace can be too. It is time for a recommitment to peace. In the present document, I offer my vision of how we can make that choice.

A WORLD AT A CROSSROADS

A GEOPOLITICAL TRANSITION

The United Nations is shaped fundamentally by the willingness of its Member States to cooperate. It was the “improvement in relations between States” (A/47/277-S/24111, para. 8) at the end of the cold war that helped forge consensus in the Security Council and empowered the Organization to address threats to collective security. It was against this backdrop that An Agenda for Peace was presented in 1992.

We are now at an inflection point. The post-cold war period is over. A transition is under way to a new global order. While its contours remain to be defined, leaders around the world have referred to multipolarity as one of its defining traits. In this moment of transition, power dynamics have become increasingly fragmented as new poles of influence emerge, new economic blocs form and axes of contestation are redefined. There is greater competition among major powers and a loss of trust between the global North and South. A number of States increasingly seek to enhance their strategic independence, while trying to manoeuvre across existing dividing lines. The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and the war in Ukraine have hastened this process. The unity of purpose expressed by Member States in the early 1990s has waned.

Today, the national security doctrines of many States speak of intensifying geostrategic competition in the decades to come. Military expenditures globally set a new record in 2022, reaching $2.24 trillion.2Nan Tian and others, “Trends in world military expenditure, 2022”, SIPRI Fact Sheet, April 2023. Arms control frameworks and crisis management arrangements that helped stabilize great power rivalries and prevent another world war have eroded. Their deterioration, at the global as well as the regional level, has increased the possibility of dangerous standoffs, miscalculations and spirals of escalation. Nuclear conflict is once again part of the public discourse. Meanwhile, some States have embraced the uncertainties of the moment as an opportunity to reassert their influence, or to address long-standing disputes through coercive means.

Geostrategic competition has triggered geoeconomic fragmentation,3Kristalina Georgieva, “Confronting fragmentation where it matters most: trade, debt, and climate action”, IMF blog, 16 January 2023. with fractures widening in trade, finance and communications and increasing concerns regarding transfers of technologies such as semiconductors. Efforts to secure access to both basic and strategic commodities, such as rare earth minerals, are transforming global supply chains. In some regions, polarized global politics are mirrored in the unravelling of several regional integration efforts that had contributed to regional stability for decades.

Nonetheless, the imperative of cooperation is evident. Unconstrained competition among nuclear powers could result in human annihilation. Failure to address other global threats poses existential risks for States and societies around the world. Even at the height of the cold war, two ideologically and politically antagonistic blocs, and an active Non-Aligned Movement, found avenues to advance common goals through international cooperation, arms control and disarmament, including through the United Nations. There are reasons to believe that Member States will continue to see the value of international cooperation even in a more fragmented and fractious global environment. They have been able to transcend their disagreements to mount collective action against critical threats, as the long-standing consensus behind the United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy demonstrates. Furthermore, a majority of States remain deeply invested in the multilateral system as essential to secure their sovereignty and independence, as well as to moderate the behaviour of major powers.

A SERIES OF INTERLOCKING THREATS

More than in any previous era, States are unable to insulate themselves from cross-boundary sources of instability and insecurity. Even the most securitized of borders cannot contain the effects posed by the warming of the planet, the activities of criminal groups or terrorists or the spread of deadly viruses. Transnational threats are converging. Their mutually reinforcing effects go well beyond the ability of any single State to manage.

The changing nature of armed conflict. The surge in the number of armed conflicts in the past decade reversed a 20-year decline.4Report of the Secretary-General on the state of global peace and security (A/74/786) In 2022, the number of conflict-related deaths reached a 28-year high.5Peace Research Institute Oslo, “New figures show conflict-related deaths at 28-year high, largely due to Ethiopia and Ukraine wars”, 7 June 2023. This has had catastrophic consequences for people and societies, including mass atrocities and crimes against humanity. Inter-State conflict may be resurging. Civil wars, which still represent the vast majority of conflicts today, are increasingly enmeshed in global and regional dynamics: close to half of all conflicts in 2021 were internationalized.6Uppsala University, “Armed conflict by type, 1946–2021”, Uppsala Conflict Data Programme database. Available at https://ucdp.uu.se/downloads/charts/graphs/png_22/armedconf_by_type.png This has increased the risk of direct confrontation among external actors, who, in certain situations, have become conflict parties in their own right. Non- State armed groups, including terrorist groups, have proliferated, and many of them retain close linkages with criminal interests. These groups often engage in illicit trafficking and diversion of small arms and light weapons and have access to the latest technology, as well as military-grade weapons acquired from poorly secured stock- piles and transfers from the illicit market, or from States themselves. The growing complexity of the conflict environment has made conflict resolution more difficult, as local and regional dynamics intersect in complex ways with the interests of external parties, and the presence of United Nations-designated terrorist groups operating across regions presents a host of challenges. Conflicts also exacerbate pre-existing patterns of discrimination. Misogyny, offline and online, fuels gender-based and sexual violence in all parts of the world, but in conflict settings the added challenges of institutional weakness, impunity and the spread of arms predominantly borne by men massively aggravate the risks.

Armed conflict has a dramatic negative effect on the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals. One quarter of humanity lives in conflict-affected areas. Conflict is a key driver for the more than 108 million people forcibly dis- placed worldwide – more than double the number a decade ago.7Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Global trends 2022”, 2022 Available at www.unhcr.org/global-trends Without a dramatic reduction in conflict, violence and the spread of weapons, the 2030 Agenda will remain out of reach for a large percentage of humanity.

Persistent violence outside of armed conflicts. The scourge of violence has shaped the lives and livelihoods not just of those in armed conflicts. Terrorism remains a global threat, even if countries in armed conflict are disproportionately affected. Misogyny is often part of the narratives used to justify such attacks, drawing attention to the intersection of extremism and gender-based violence. Other forms of violence have become existential challenges across many parts of the world. From 2015 to 2021, an estimated 3.1 million people lost their lives as a result of intentional homicides, a shocking figure which dwarfs that of the estimated 700,000 people who died in armed conflicts during the period.8United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Global Study on Homicide 2023 (forthcoming) Organized crime was responsible for as many deaths in this period as all armed conflicts combined. While roughly four out of five homicide victims are men, this violence has terrifying implications for women. Their killings are predominantly gender-based.9UNODC and United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN- Women), “Gender-related killings of women and girls (femicide/feminicide): global estimates of gender-related killings of women and girls in the private sphere in 2021 – improving data to improve responses”, 2022. Globally, an estimated one out of two children aged 2–17 years suffer some form of violence each year.10World Health Organization (WHO) and others, Global Status Report on Preventing Violence against Children 2020 (Geneva, WHO, 2020).

The perils of weaponizing new and emerging technologies. Technology and warfare have been intrinsically linked throughout human history. From sharpened stones to atom splitting, technologies to advance human existence have also been repurposed for destruction. Our era is no exception. Rapidly advancing and converging technologies have the potential to revolutionize conflict dynamics in the not-too-distant future. Incidents involving the malicious uses of digital technologies, by State and non-State actors, have increased in scope, scale, severity and sophistication (A/76/135, para. 6). The proliferation of armed uncrewed aerial systems (also referred to as drones) in armed conflict is another notable trend, with increased use of varying degrees of sophistication by both States and non-State actors, including terrorists. They have often been deployed against civilian targets, including critical infrastructure, and have presented a threat to peace operations. Developments in artificial intelligence and quantum technologies, including those related to weapons systems, are exposing the insufficiency of existing governance frame- works. The magnitude of the artificial intelligence revolution is now apparent, but its potential for harm – for societies, economies and warfare itself – is unpredictable. Advances in the life sciences have the potential to give individuals the power to cause death and disruption on a global scale.

The emergence of powerful software tools that can spread and distort content instantly and massively heralds a qualitatively different, new reality. As my policy brief on the integrity of public information11United Nations, “Our common agenda policy brief 8: information integrity on digital platforms”, June 2023. illustrates, misinformation, disinformation and hate speech are rampant on social media platforms and are deadly in volatile societal and political contexts. The ease of access to these technologies for non-State actors, in particular terrorist groups, poses a significant threat. Terrorist groups and affiliated supporters have misused these technologies to coordinate and plan attacks, including cyberattacks, to recruit new members and to incite hatred and violence. Meanwhile, social media platforms, operating largely without human rights-compliant regulations against online harm, have developed irresponsible business models that prioritize profit at the expense of the well-being and safety of their users and societies.

Rising inequalities within and among nations. Halfway to 2030, the rallying cry of the Sustainable Development Agenda to leave no one behind remains aspirational, with only 12 per cent of the Sustainable Development Goals on track and the rest in jeopardy. Targets under Goal 17 are a litany of unmet commitments. Inequalities in finance, trade, technology and food distribution and security are being entrenched rather than dismantled through a global partnership for development. Income inequality between the richest and poorest nations has increased as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic12The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022 (United Nations publication, 2022). and is still higher than inequality within most countries.13World Social Report 2020: Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World (United Nations publication, 2020). The relationship between inequality and conflict is non-linear and indirect, but we know that inequality can lead to conflict when it overlaps with differences in access and opportunities across groups defined around specific identities.14World Bank and United Nations, Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict (Washington, D.C., World

Bank, 2018). Vertical inequalities – those between the rich and poor within a society – also remain a key challenge and are closely associated with other forms of violence.15UNODC, “Global study on homicide: executive summary”, July 2019.

Shrinking space for civic participation. Growing grievances and demands for the meaningful engagement of different groups in the political, economic, social and cultural lives of their societies are increasingly met by States through the imposition of undue restrictions on the human rights of their citizens and by limiting avenues for participation and protest. Demands for more civic engagement have also been met with physical attacks and the use of force. Of note is the rise in threats, persecution and acts of violence against women, including those in politics, and human rights defenders. Digital tools have created previously inconceivable avenues for civic participation, in particular for young people. The same tools have been used to restrict civic space, however, by disabling the channels available for people to organize themselves or by tracking or surveilling those who protest.

The climate emergency. The uneven suffering created by the effects of climate change ranks among the greatest injustices of this world. The most vulnerable communities, including in small island developing States, the least developed countries and those affected by conflict, bear the brunt of a crisis that they did not create. Where record temperatures, erratic precipitation and rising sea levels reduce harvests, destroy critical infrastructure and displace communities, they exacerbate the risks of instability, in particular in situations already affected by conflict. Rising sea levels and shrinking land masses are an existential threat to some island States. They may also create new, unanticipated areas of contestation, leading to new or resurgent disputes related to territorial and maritime claims. Climate policies and green energy transitions can offer avenues for effective peacebuilding and the inclusion of women, Indigenous communities, the economically disadvantaged and youth. However, they can also be destabilizing if not managed properly. Failure to tackle head-on the challenges posed by climate change, and the inequalities it creates, through ambitious mitigation, adaptation and implementation of the loss and damage agenda, bolstered by adequate climate finance, will have devastating effects, for the planet as well as development, human rights and our shared peacebuilding objectives.

A NORMATIVE CHALLENGE

One of the greatest achievements of the United Nations is the development of a body of inter- national law that governs relations among sovereign States. International law fosters predict- ability of behaviour, which increases trust. Even as Member States recognize and emphasize the importance of international law, it is sometimes challenged. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation represents one of the latest such challenges. Each violation of international law is dangerous, as it undermines one of the purposes of the United Nations contained in Article 1 of its Charter.

As we mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, human rights are facing a pushback in all regions. We see a significant global retrenchment of human rights16United Nations, “The highest aspiration: a call to action for human rights”, 2020. and an erosion of the rule of law, including in contexts of armed conflict. Despite the recognition that the rule of law is the foundation for fair, just and peaceful societies, we are at grave risk of a rule of lawlessness, which would exacerbate global instability and turmoil. Growing polarization among States has also begotten competing interpretations of human rights norms. There are increasing challenges to advancing certain human rights, an underlying criticism that implementation has been subject to double standards and calls for national prioritization of international norms. For example, some States have voiced concerns that civil and political rights have been prioritized at the international level, at the expense of social, economic and cultural rights. However, these arguments have also been raised at times as a way to shift the focus away from a State’s own short- comings in meeting its international obligations. The position of the United Nations is emphatic and principled: all rights, be they civil, political, social, economic or cultural, are indivisible. All matter and ought to be realized fully, including the right to development.

Closely connected to this is the growing back- lash against women’s rights, including on sexual and reproductive health. We must dismantle the patriarchy and oppressive power structures which stand in the way of progress on gender equality or women’s full, equal and meaningful participation in political and public life. We – Governments, the United Nations and all segments of society – must fight back and take concrete action to challenge and transform gender norms, value systems and institutional structures that perpetuate exclusion or the status quo.

The United Nations is, at its core, a norms-based organization. It owes its birth to an international treaty, the Charter, signed and ratified by States. It faces a potentially existential dilemma when the different interpretations by Member States of these universal normative frameworks become so entrenched as to prevent adequate implementation. Rebuilding consensus on the meaning of and adherence to these frameworks is an essential task for the international system.

Principles for an effective collective security system

The collective security system envisioned in the Charter offers the promise of an ever more peaceful and just world. Although it has struggled to live up to its potential and has fallen disastrously short at times, its achievements are manifold, from advancing decolonization and promoting nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation to forestalling and mediating armed conflict, mounting large- scale humanitarian responses and promoting international norms and justice. Today, however, the chasm is widening between the potential of collective security and its reality.

Collective security is gravely undermined by the failure of Member States to effectively address the global and interlocking threats before them, to manage their rivalries and to respect and reinforce the normative frameworks that both govern their relations with each other and set international parameters for the well-being of their societies. These phenomena are rooted in the neglect of a set of principles that are the basis for friendly relations and cooperation among nations and within societies: trust, solidarity and universality. If we are to rise to the challenge, it is in these principles, taken together and carried forward by all States, and within countries, that action for peace must be grounded.

TRUST

In a world of sovereign States, international cooperation is predicated upon trust. Cooperation cannot work without the expectation that States will respect the commitments which they have undertaken. The Charter provides a set of norms against which the trustworthiness of each State should be assessed. In An Agenda for Peace in 1992, the Secretary-General warned of the need for consistent, rather than selective, application of the principles of the Charter, “for if the perception should be of the latter, trust will wane and with it the moral authority which is the greatest and most unique quality of that instrument” (A/47/277-S/24111, para. 82).

Trust is the cornerstone of the collective security system. In its absence, States fall back to their basic instinct to ensure their own security, which, when reciprocated, creates more insecurity for all. To help reinforce trust, confidence-building mechanisms have been of great value. These can range from crisis management hotlines to the monitoring of ceasefires or bilateral arms control agreements with verification provisions.17See https://disarmament.unoda.org/cbms/repository-of-military-confidence-building-measures/ Regional organizations and frameworks can play a crucial role in this regard.

The impartiality of the Secretariat is vital in helping to build trust among Member States. The good offices of the Secretary-General, and her or his envoys and mediators, are an impartial vehicle to help forge common ground between States or conflict parties in even the most complex of circumstances. Peacekeeping operations have proven effective in helping parties overcome mutual mistrust18Barbara Walter, Lise Morje Howard and Virginia Page Fortna, “The extraordinary relationship between peacekeeping and peace”, British Journal of Political Science, vol. 51, No. 4 (October 2021). and can help build trust in national institutions. Various initiatives led by the United Nations to promote military transparency, such as the United Nations Report on Military Expenditures19See https://disarmament.unoda.org/convarms/milex/ or the Register of Conventional Arms,20See https://disarmament.unoda.org/convarms/register/ are designed to increase inter-State trust and confidence-building through enhanced transparency.

If trust among States is vital for international cooperation, trust between Governments and their people is integral to the functioning of societies. Over the past several decades, a consistent finding is that trust in public institutions has been on the decline globally.21United Nations, “Trust in public institutions: trends and implications for economic security”, Decade of Action Policy Brief, No. 108, June 2021. Low levels of trust indicate low social cohesion, which in turn is often closely linked to high levels of economic, political and gender inequalities.22Human Development Report 2019: Beyond Income, Beyond Averages, Beyond Today – Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century (United Nations publication, 2019) The waves of protests that have occurred globally throughout the past decade are an example of the growing alienation of citizens, in particular young people, who do not trust public institutions and other institutional mechanisms to peacefully address grievances, in particular in a context where civic space has become narrower.

SOLIDARITY

A community of nations must be underpinned by a sense of fellowship that recognizes a collective duty to redress injustices and support those in need. My report on Our Common Agenda was, at its core, a call for more solidarity. The asymmetries and inequities that exist among and within States, and the structural obstacles that sustain these, are as much a barrier to peace as they are for development and human rights.23Human Development Report 2019: Beyond Income, Beyond Averages, Beyond Today – Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century (United Nations publication, 2019). If the purposes of the Charter are to be achieved, redressing the pervasive historical imbalances that characterize the international system – from the legacies of colonialism and slavery to the deeply unjust global financial architecture and anachronistic peace and security structures of today – must be a priority.

The concept of solidarity is embedded in the work of the United Nations. In the Millennium Declaration,24General Assembly resolution 55/2 the General Assembly recognized solidarity as one of the essential values for the twenty-first century, noting that global challenges must be managed in a way that distributes the costs and burdens fairly in accordance with basic principles of equity and social justice. The concept of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capacities, in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, for example, is grounded in this idea. Sustainable Development Goal 1725See https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal17 – revitalizing the global partnership for development – remains a yardstick: from fair trade and technology transfers to debt relief and higher levels of development assistance, it outlines measurable actions to redress imbalances at the global level. Together with the wider 2030 Agenda, its reach goes beyond sustainable development and pro- vides us with a blueprint for addressing underlying causes of conflict comprehensively.

Comprehensive commitments to equity and burden-sharing have been made explicit in the climate action,26See United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (see A/AC.237/18 (Part II)/Add.1 and Corr.1, annex I) humanitarian27Solidarity lies at the root of obligations under international refugee law, as reiterated by the Executive Committee of UNHCR in its decision no. 52 (XXXIX) on International Solidarity and Refugee Protection (see A/43/12/Add.1, chap. III.C). In the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, solidarity is emphasized as a core principle (see General Assembly resolution 73/195, annex) and sustainable development28See https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal17 agendas. They are equally integral to international peace and security. The global partnership for peacekeeping is an example of such solidarity, with States deploying their troops and police, often in situations of great harm and removed from their national interests, to support those in need and in the service of global peace. We must also ensure that the steps that we take to address the perils of weaponizing new and emerging technologies do not restrict access for countries of the global South to the huge benefits promised by such technologies for the advancement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

At the national level, solidarity has steadily eroded over the past decades. Economic policies advocating deregulation and limited government have concentrated wealth, dismantled social protections and disempowered the State to address mounting social challenges. The international financial crisis in 2008 as well as the COVID-19 pandemic have compounded the effects of these policies. Increasing discontent is compounded by rising inequalities in access to the more empowering opportunities of the twenty-first century – such as housing, higher education and technology – and by the lack of social mobility.

UNIVERSALITY

Two of the foundational principles of the United Nations are the sovereign equality of all its Members and the fulfilment by all Member States of their obligations under the Charter in good faith. Article 2 calls on all Member States to settle their international disputes by peaceful means and to refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations. The universality of the Charter is well recognized across the peace and security, sustainable development and human rights pillars of the United Nations. The 2030 Agenda was articulated around the universal promise of “leaving no one behind”, which requires a commitment by all States, rich or poor, to fulfil development targets. Similarly, the principle of universality is a cornerstone of international human rights law, embodied in Article 55 of the Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and reflected more recently in the creation of the universal periodic review.29See https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/upr/upr-main

Despite the universality of the norms underpinning them, peace and security engagements have not always been understood on a universal basis. They have at times been perceived as selective, or marred by double standards. A more deliberate and explicitly universal approach to the prevention of conflict and violence would align with the approach guiding action across the human rights and sustainable development pillars. It would help address two challenges: first, many of today’s threats to peace and security require universal action and mitigation by all States; second, instability, violence and the potential for conflict are not restricted to only a few States, as growing risks, while differentiated, exist in developed, middle income and developing States alike. The challenges of our times require universality in the implementation of commitments, not selectivity.

A vision for multilateralism in a world in transition

Achieving peace and prosperity in a world of interlocking threats demands that Member States find new ways to act collectively and cooperatively. My vision for a robust collective security system rests on Member States moving away from a logic of competition. Cooperation does not require States to forgo their national interest, but to recognize that they have shared goals. To achieve this vision, we must adapt to the geopolitical realities of today and the threats of tomorrow. I propose a series of foundational steps which, if implemented by Member States, would create opportunities and momentum currently lacking in collective action for peace. These building blocks, as well as the actions proposed in the next section, take into consideration the recommendations put forward by the High-level Advisory Board on Effective Multilateralism.

The Charter and international law. Without the basic norms enshrined in the Charter – such as the principles of sovereignty, non-intervention in domestic affairs and the pacific settlement of disputes – international relations could degenerate into chaos. The obligation for Member States to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, as contained in Article 2 (4) of the Charter, remains as vital as ever. The legitimacy of collective enforcement actions authorized by the Security Council must be carefully safeguarded.

Diplomacy for peace. The driving force for a new multilateralism must be diplomacy. Diplomacy should be a tool not only for reducing the risks of conflict but for managing the heightened fractures that mark the geopolitical order today and carving out spaces for cooperation for shared interests. This demands, above all else, a commitment to the pacific settlement of disputes. The underutilization of the different tools referred to in Article 33 of the Charter remains one of our greatest collective shortcomings. The pacific settlement of disputes does not demand new tools, for those that exist remain relevant, potent and based on consent. However, they often fall short of their promise when the will of Member States to deploy them is lacking. It is incumbent on all actors to rely on peaceful means as their first line of defence to prevent armed conflict.

Prevention as a political priority. From my first day in office, I have called on Member States to prioritize prevention. The evidence is staggering: prevention saves lives and safeguards development gains. It is cost effective.30World Bank and United Nations, Pathways for Peace However, it remains chronically underprioritized. For A New Agenda for Peace to succeed, Member States must go beyond lip service and invest, politically and financially, in prevention. Effective prevention requires comprehensive approaches, political courage, effective partnerships, sustainable resources and national ownership. Above all, it needs greater trust – among Member States, among people and in the United Nations.

Mechanisms to manage disputes and improve trust. Throughout the cold war, confidence-building and crisis management mechanisms helped forestall direct confrontations among major powers, a third world war and nuclear cataclysm.

However, these structures have deteriorated in the past decade and have not kept pace with the shifting geopolitical environment. We need durable and enforceable mechanisms, in particular among nuclear powers, that are resilient to shocks which could trigger escalation. Efforts to enhance the transparency of military posture and doctrines, including those related to new technologies, are critical. Avoiding direct confrontations is the primary goal of these crisis management systems, but they should be underpinned by more sustained dialogue and shared data, at the bilateral and multilateral level, to address the underlying sources of tensions and foster a common understanding of existing threats.

The Security Council can serve as one of these mechanisms. Its ability to manage disputes among its permanent members may be limited owing to the veto, but the engagement of the P5 in the day-to-day business of the Council – in close cooperation with the elected members – can be a powerful incentive for dialogue and compromise, which in turn can help rebuild trust. The permanent members have not only a special responsibility, but a shared interest, in maintaining the credibility of the Council. I call upon them to work together despite their differences to meet their responsibilities under Chapters V to VIII of the Charter.

Robust regional frameworks and organizations. In the face of growing competition at the global level and threats that are increasingly transnational, we need regional frameworks and organizations, in accordance with Chapter VIII of the Charter, that promote trust-building, transparency and détente. We also need strong partnerships between the United Nations and regional organizations. Regional frameworks and organizations are critical building blocks for the networked multilateralism that I envisage. They are particularly urgent in regions where long-standing security architectures are collapsing or where they have never been built.

National action at the centre. Member States have the primary responsibility, as well as an ability unmatched by others, to prevent conflict and build peace. Decades of practice have demonstrated that successful engagements in this area are led and owned by national actors. That does not mean that State actors can implement these initiatives alone – the involvement of all society is necessary for their success. Too many opportunities to address the drivers of conflict within a State are lost because of lack of trust and a concern that such action would internationalize issues that are domestic in nature. The fear of external interference has at times been a significant inhibitor of early national action. A clear signal of a shift in focus to the national level – to national ownership and nationally defined priorities – would help assuage such concerns and build trust. This does not preclude, however, that situations deemed by the Security Council to be a threat to international peace and security might require international leadership and attention.

People-centred approaches. For national action to sustain peace to be effective, it must be people-centred, with the full spectrum of human rights at its core. Governments must restore trust with their constituents by engaging with, protecting and helping realize the aspirations of the people that they represent. The United Nations must follow suit. Civil society actors, including women human rights defenders and women peacebuilders, play a crucial role in building trust in societies, by representing the most vulnerable or marginalized and those often unrepresented in political structures. Displaced people often face compounded levels of vulnerability, and addressing their needs requires political solutions and political will.

Eradication of violence in all its forms. In the 2030 Agenda, Member States committed to significantly reducing all forms of violence and related death rates. My vision for A New Agenda for Peace is designed to boost progress towards this goal. Violence perpetrated by organized criminal groups, gangs, terrorists or violent extremists, even outside of armed conflicts, threatens lives and livelihoods around the world. Gender-based violence can be a precursor of political violence and even armed conflict. Not all forms of violence are linked to peace and security dynamics, and eradicating violence in all its forms should not be misunderstood for a call to internationalize domestic issues. There is, however, much to learn from how conflict and violence have been addressed through prevention and peacebuilding approaches at the national level. Every violent death is preventable, and it is our collective moral responsibility to achieve this goal. Building on Sustainable Development Goal 16.1,31See https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal16 I invite each Member State to consider the ambitious target of halving violent death rates in their societies by 2030.

Prioritizing comprehensive approaches over securitized responses. Responses to violence, including addressing the threat posed by non-State armed groups such as terrorists and violent extremists, cannot be effective if not part of a comprehensive approach with a political strategy at its core. Failure to tackle the root causes of violence can lead to oversecuritized responses, including in counter-terrorism and counterinsurgency operations. These can be counterproductive and reinforce the very dynamics they seek to overcome, as their far-reaching consequences – blowback from local populations, human rights violations and abuses, exacerbation of gender inequalities and distortion of local economies – can be powerful drivers for recruitment into terrorist or armed groups. Military engagement, within the limits of international law, including international humanitarian law and international human rights law, may be necessary. However, it should be underpinned by development and political strategies to intelligently tackle the structural drivers of conflict. United Nations and regional peace operations can play important roles in this respect: mobilizing collective action, promoting comprehensive approaches with strong civilian, police and development dimensions and – most importantly – pursuing political solutions and sustainable peace. Similarly, effective disarmament actions could be a powerful preventive tool in support of comprehensive responses.

Dismantling patriarchal power structures. For as long as gendered power inequalities, patriarchal social structures, biases, violence and discrimination hold back half our societies, peace will remain elusive. We must listen to, respect, uphold and secure the perspectives of women impacted by compounding forms of discrimination, marginalization and violence. This includes Indigenous women, older persons, persons with disabilities, women from racial, religious or ethnic minorities and LGBTQI+ persons and youth. Gendered power dynamics also impact and severely constrain men and boys – with devastating consequence for us all. Transformative progress on the women and peace and security agenda requires consideration of the role of men, who have traditionally dominated decision-making, and addressing intergenerational power dynamics.

Ensuring that young people have a say in their future. Young people, in particular, have a key role to play and must be enabled to participate effectively and meaningfully. As I noted in my policy brief on youth engagement,32United Nations, “Our Common Agenda policy brief 3: meaningful youth engagement in policy and decision-making processes”, April 2023 our youth are essential to identifying new solutions that will secure the breakthroughs that our world urgently needs. Their active participation in decision-making processes enhances the legitimacy of peace and security initiatives. Governments must encourage greater representation of youth in decision-making and elected positions and enact special measures to ensure their participation. The youth, peace and security agenda must be institutionalized and funded.

Financing for peace. Action for peace, not solely to address crises and their immediate consequences, but to prevent them and tackle their underlying drivers, requires resources commensurate to the complexity of this endeavour. This starts with bolstering the implementation of all the Sustainable Development Goals, in particular Goal 17, which would drastically improve the ability of developing countries to close their current financing gaps. It is not charity, but eminently fair, to redress past and current injustices, in particular those in international trade and the global financial system. It must also involve a significant increase – in quantity as well as sustainability and predictability – in resources that are channeled to support national action for peace.

Not a single conflict-affected country is on track to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals related to hunger, good health or gender equality.33Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2022 (Paris, 2022) In the declaration on the commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the United Nations, Member States committed to promoting peace and preventing conflicts. They must make the case to their legislatures and treasuries that these Goals, which are the enablers of so many others, require stepped-up investment now, despite pressures pulling in the opposite direction. Investing in prevention is manifestly an investment in the 2030 Agenda. International financial institutions have an important responsibility in this regard. They must help redress the current inequalities in the global financial system.34United Nations, “Our Common Agenda policy brief 6: reforms to the international financial architecture”, May 2023 But their responsibility goes farther. They should be agents not only for global financial stability, but for peace. This requires that international financial institutions more systematically align their mechanisms with the needs of the collective security system and ensure that Member States affected by conflict and violence have a greater say in their decision-making.

Strengthening the toolbox for networked multilateralism. A universal and more effective approach to peace and security and the interlocking threats that Member States face requires a more comprehensive and flexible use of the tools at our disposal. The United Nations, regional partners and other actors have developed a rich and diverse toolbox: good offices and mediation to support political processes; action to promote disarmament, non-proliferation and arms control; counter-terrorism and the prevention of violent extremism; the promotion of human rights and the undertaking of long-term work to bolster the rule of law and access to justice; and the engagement of peace operations. These tools can be deployed to help societies tackle the drivers of conflict, as well as its manifestations. They have often been approached as discrete; more deliberate, coherent and integrated action to draw on this diverse toolkit in support of Member States, at the national, regional and global levels, is required. This has to go beyond traditional peace and security tools and encompass the full range of capacities needed to respond to the magnitude of global threats that we face.

An effective and impartial United Nations Secretariat. My vision for an effective collective security system relies on an international civil service that is strong, efficient and impartial. Member States must respect the exclusively international character of the United Nations Secretariat and not seek to influence it. The impartiality of the Secretariat is and will remain its strongest asset, and needs to be fiercely guarded, as required by the Charter, particularly as fractures at the global level widen. Trust on the part of Member States in the international civil service, in turn, demands that the latter be truly representative of the diversity of the membership. The scale of challenges facing us today and tomorrow, and the unforeseen nature and impact of technological change, will also demand a great deal of humility, creativity and perseverance from the international civil service.

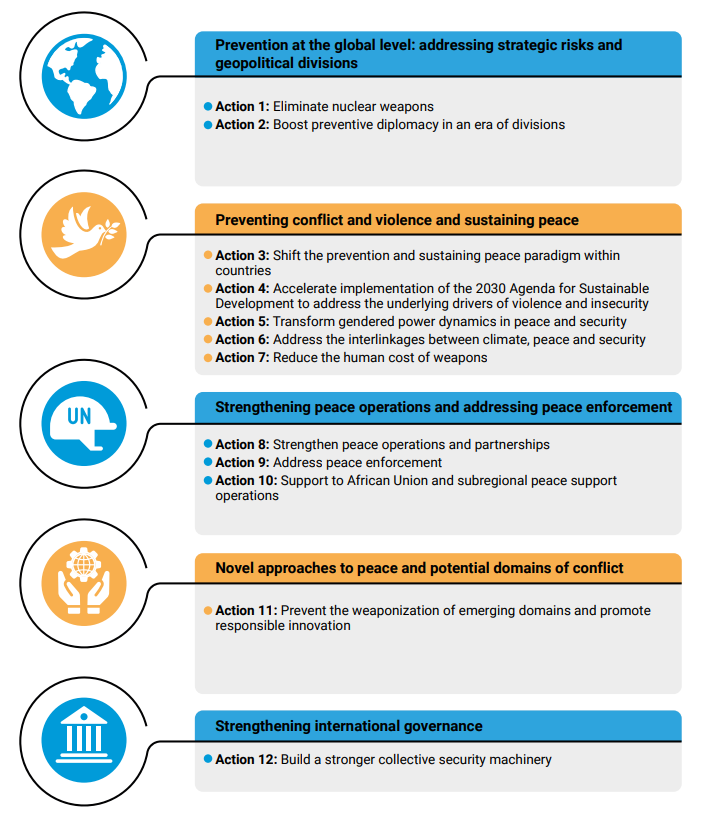

Recommendations for action

To achieve more effective multilateral action for peace, the following recommendations are presented for the consideration of Member States.

PREVENTION AT THE GLOBAL LEVEL: ADDRESSING STRATEGIC RISKS AND GEOPOLITICAL DIVISIONS

In an era of global fragmentation, where the risk of bifurcating politics, economies and digital spheres is acute, and where nuclear annihilation and a third world war are no longer completely unthinkable, we must step up our global prevention efforts. The United Nations should be at the centre of these efforts; to eliminate nuclear weapons, to prevent conflict between major powers; and to manage the negative impacts of strategic competition, which could have implications for the poorest and most vulnerable countries. By helping Member States manage disputes peacefully and preventing competition from escalating into confrontation, the United Nations is the pre-eminent hub of global prevention efforts.

ACTION 1: ELIMINATE NUCLEAR WEAPONS

Fifty-five years since the adoption of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, the nuclear disarmament and arms control regime is eroding, nonproliferation is being challenged, and a qualitative race in nuclear armaments is under way. Member States must urgently reinforce the barrier against the use of nuclear weapons. The statement by the permanent members of the Security Council in January 2022, reaffirming that a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought, was a welcome step. However, risk reduction does not suffice when the survival of humanity is at stake. The non-proliferation regime needs to be buttressed against a growing array of threats. Non-proliferation and disarmament are two sides of the same coin – progress in one requires progress in the other. As stated in my agenda for disarmament, the existential threat that nuclear weapons pose to humanity must motivate us to work towards their total elimination.

Recommendations

- Recommit urgently to the pursuit of a world free of nuclear weapons and reverse the erosion of international norms against the spread and use of nuclear weapons.

- Pending the total elimination of nuclear weapons, for States possessing nuclear weapons, commit to never use them. Take steps to avoid mistakes or miscalculations; develop transparency and confidence-building measures; accelerate the implementation of existing nuclear disarmament commitments; and reduce the role of nuclear weapons in national security strategies. Engage in dialogue on strategic stability and to elaborate next steps for further reductions of nuclear arsenals.

- States with the largest nuclear arsenals have a responsibility to negotiate further limits and reductions on strategic nuclear weapons.

- For the Security Council, commit to the imposition of punitive measures to restore international peace and security for any use of or threat of use of nuclear weapons, consistent with its mandate.

- Reinforce the non-proliferation regime through adherence to the highest nuclear safeguards standards, ensuring that they keep pace with technological developments and ensure accountability for non-compliance with non-proliferation obligations. Strengthen measures to prevent the acquisition of weapons of mass destruction by non-State actors.

ACTION 2: BOOST PREVENTIVE DIPLOMACY IN AN ERA OF DIVISIONS

One of the greatest risks facing humanity today is the deterioration in major power relations. It raises anew the spectre of inter-State war and may hasten the emergence of blocs with parallel sets of trade rules, supply chains, currencies, Internets or approaches to new technologies. Diplomacy must be prioritized by all sides to bridge these growing divides and ensure that unmitigated competition does not trample humanity. Diplomatic engagement is important among countries that think alike. However, it is crucial between those which disagree. During moments of high geopolitical tension in recent history, from Suez to the Cuban missile crisis, diplomacy saved the world from war or helped find ways to end it. It requires risk-taking, persistence and creativity. The Black Sea Initiative shows that, even in the most complex of situations, diplomatic engagement and innovative use of multilateral instruments can help find common ground.

Diplomacy at the global level must both reinforce and be bolstered by regional frameworks that build cooperation among Member States. Such frameworks help States address differences through concrete steps and protocols and inspire confidence. They can encompass a range of confidence-building measures and norms to reduce tensions and give rise to greater regional cooperation, as was the case during the Helsinki process in Europe.

I commit to deploying my good offices to help Member States manage deepening divisions in global politics and prevent the outbreak of conflict. My good offices are available also to assist Member States in building or rebuilding regional frameworks. They are equally applicable to reinforce disarmament and in new potential domains such as outer space or cyberspace. I stand ready to work with all Member States to help overcome the current divides in politics, economics and technology and will make my envoys and senior officials available to pursue this goal. Ultimately, the good offices of the Secretary-General are a tool not just to address the immediate threat of armed conflict but to protect humanity’s shared future.

Recommendations

- Make greater use of the United Nations as the most inclusive arena for diplomacy to manage global politics and its growing fractures, as a platform for Member States to engage even when they lack formal diplomatic relations, are at war or do not recognize each other or one side.

- Seek the good offices of the Secretary- General to support action to reverse the deterioration of geopolitical relations and keep diplomatic channels open. This could include the establishment of United Nations-facilitated or sponsored frameworks to encourage crisis communications mechanisms and agree on responsible behaviours and manage incidents in the naval, aerial, cyberspace and space domains to guard against escalation between major powers.

- Reinforce and strengthen United Nations capacities to undertake diplomatic initiatives for peace and support United Nations envoys deployed to that effect. Bringing together global and regional actors, design new models for diplomatic engagement that can address the interests of all involved actors and deliver mutually beneficial outcomes.

- Building on the experience of the United Nations in the Black Sea Initiative, seek the good offices of the Secretary-General and his convening powers to protect global supply and energy chains and prevent economic links from fraying and bifurcating as a result of strategic competition. This could include finding bespoke solutions to future supply chain disruptions of key commodities and services, as well as major digital disruptions.

- Deploy the Secretary-General’s good offices to maintain a free, open and secure Internet and prevent a rupturing in digital systems between States.

- Repair regional security architectures where they are in danger of collapsing; build them where they do not exist; and enhance them where they can be further developed. The United Nations can work to further such regional efforts in a convening and supporting role.

- For the United Nations, regional organizations and their respective Member States, operationalize rapid responses to emerging crises through active diplomatic effort.

PREVENTING CONFLICT AND VIOLENCE AND SUSTAINING PEACE

ACTION 3: SHIFT THE PREVENTION AND SUSTAINING PEACE PARADIGM WITHIN COUNTRIES

In order to complement diplomatic action at the international and regional level, a focus on prevention at the national level is essential. In today’s interlocking global risk environment, prevention cannot apply only to conflict-affected or “fragile” States. To be successful, prevention first requires an urgent shift in approach, by which all States agree to recognize prevention and sustaining peace as goals that all commit to achieve. In line with Sustainable Development Goal 16.1, a universal approach to prevention means tackling all forms of violence, not only in conflict settings. Prevention has been undercut by a lack of trust, as it is often perceived as a cloak for intervention. A renewed commitment to prevention must start by addressing that lack of trust, along with investment in national prevention capacities and infrastructures for peace. Whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches grounded in sustainable development that leaves no one behind would make national prevention strategies more effective. They should be multidimensional, people-centred and inclusive of all the different components of society. The United Nations, when so requested, will offer its extensive support for the development and implementation of these strategies.

Recommendations

- Develop national prevention strategies to address the different drivers and enablers of violence and conflict in societies and strengthen national infrastructures for peace. These strategies can help reinforce State institutions, promote the rule of law and strengthen civil society and social cohesion, so as to ensure greater tolerance and solidarity.

- In line with my call to action for human rights,35United Nations, “The highest aspiration: a call to action for human rights”, 2020 ensure that human rights in their entirety – economic, social and cultural rights as well as civil and political rights – are at the heart of national prevention strategies, as human rights are critical to guarantee conditions of inclusion and protect against marginalization and discrimination, thus preventing grievances before they arise.

- Recognize the fundamental importance of the rule of law as the basis for multilateral cooperation and political dialogue, in accordance with the Charter, and as a central tenet of sustaining peace.

- Member States seeking to establish or strengthen national infrastructures for peace should be able to access a tailor-made package of support and expertise.

- Provide more sustainable and predictable financing, including through assessed contributions36See General Assembly resolution 76/305 to peacebuilding efforts, in particular the Peacebuilding Fund, to support these strategies, as a matter of urgency.

- For groups of Member States and regional organizations, develop prevention strategies with cross-regional dimensions to address transboundary threats, collectively harvesting and building on the wealth of knowledge and expertise existing at the national level on effective conflict prevention measures.

ACTION 4: ACCELERATE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE 2030 AGENDA FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT TO ADDRESS THE UNDERLYING DRIVERS OF VIOLENCE AND INSECURITY

Prevention and sustainable development are interdependent and mutually reinforcing. Full achievement of the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals is critical, both in their own right and because sustainable development is ultimately the only way to comprehensively address the interlinked, multidimensional drivers of violence and insecurity. However, the speed of implementation of the 2030 Agenda is falling short of the pace required to meet its ambition, in particular in countries affected by conflict. People must be at the centre of our efforts to attain development, overcome poverty and reduce the risks of conflict and violence arising from inequality, marginalization and exclusion. International financial institutions have a responsibility to lend their support and, more broadly, to better address the needs of developing countries, as highlighted in my policy brief on reforms to the international financial architecture.United Nations, “Our Common Agenda policy brief 6: reforms to the international financial architecture”, May 202337United Nations, “Our Common Agenda policy brief 6: reforms to the international financial architecture”, May 2023

Recommendations

- Accelerate implementation of proven development pathways that enhance the social contract and human security, such as education and health care.

- Consider new and emerging ways to protect livelihoods and provide social protection in communities emerging from conflict and in post-conflict countries, such as through temporary universal basic incomes, which can promote resilience and social cohesion and break the cycle of violence.

- For international financial institutions, align funding mechanisms to help address the underlying causes of instability through inclusive sustainable development.

ACTION 5: TRANSFORM GENDERED POWER DYNAMICS IN PEACE AND SECURITY

As generational gains in women’s rights hang in the balance around the world, so does the transformative potential of the women and peace and security agenda. Incrementalism has not worked and the realization of the agenda in its entirety is urgent. More political will is required. Precipitating women’s meaningful participation in all decision-making, eradicating all forms of violence against women, both online and offline, and upholding women’s rights would not just help shift power, but also result in giant steps forward in sustaining peace.

Recommendations

- Introduce concrete measures to secure women’s full, equal and meaningful participation at all levels of decision- making on peace and security, including via gender parity in national government cabinets and parliaments, and in local institutions of governance. Support quotas, targets and incentives by robust accountability frameworks with clear milestones towards achieving women’s equal participation.

- Commit to the eradication of all forms of gender-based violence and enact robust and comprehensive legislation, including on gender-based hate speech, tackle impunity for perpetrators and provide services and protection to survivors.

- Provide sustained, predictable and flexible financing for gender equality. Allocate 15 per cent of official development assistance (ODA) to gender equality, and provide a minimum of 1 per cent of ODA in direct assistance to women’s organizations, especially grass-roots groups mobilizing for peace.

ACTION 6: ADDRESS THE INTERLINKAGES BETWEEN CLIMATE, PEACE AND SECURITY

It is critical to find concrete and mutually beneficial ways to address the effects of the climate crisis and respond to the urgent call for action from countries on the front lines. Increasing climate-related investment in conflict contexts is critical: only a very small share of climate finance flows to these countries, where compounding risk factors increase vulnerability to climate shocks. Climate policies must be designed in such a way that they do not lead to adverse effects on societies and economies and do not lead to the emergence of new grievances that can be instrumentalized politically. A business-as-usual approach will fail in a warming world. Innovative solutions to address the climate crisis, protect the most vulnerable, tackle the differentiated impacts on women and men and promote climate justice will send a resounding signal of solidarity.

Recommendations

- Recognize climate, peace and security as a political priority and strengthen connections between multilateral bodies to ensure that climate action and peacebuilding reinforce each other.

- For the Security Council, systematically address the peace and security implications of climate change in the mandates of peace operations and other country or regional situations on its agenda.

- Establish, under the aegis of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a dedicated expert group on climate action, resilience and peacebuilding to develop recommendations on integrated approaches to climate, peace and security.

- Establish a new funding window within the Peacebuilding Fund for more risk-tolerant climate finance investments.

- For the United Nations system, regional and subregional organizations, establish joint regional hubs on climate, peace and security to connect national and regional experiences, provide technical advice to Member States and help accelerate progress on this agenda.

ACTION 7: REDUCE THE HUMAN COST OF WEAPONS

At the heart of our peace and security engagements is a commitment to save human beings from violence. Armed conflicts are increasingly fought in populated centres, with devastating and indiscriminate impacts on civilians. Pursuant to Article 26 of the Charter, we must reverse the negative impact of unconstrained military spending and focus on the profound negative societal effects of public resources diverted to military activity rather than sustainable development and gender equality – an issue long emphasized as a concern, including in the Beijing Declaration and

Platform for Action38www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/01/beijing-declaration – and adopt approaches underpinned by the imperative to address the humanitarian, gendered, disability and age-related impacts of certain weapons, methods and means of warfare. Member States should commit to reducing the human cost of weapons by moving away from overly securitized and militarized approaches to peace, reducing military spending and enacting measures to foster human-centred disarmament.

Recommendations

- Building on Securing Our Common Future: An Agenda for Disarmament:

- Strengthen protection of civilians in populated areas in conflict zones, take combat out of urban areas altogether, including through the implementation of the Political Declaration on Strengthening the Protection of Civilians from the Humanitarian Consequences Arising from the Use of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas, adopted on 18 November 2022, and establish mechanisms to mitigate and investigate harm to civilians and ensure accountability of perpetrators;

- Achieve universality of treaties banning inhumane and indiscriminate weapons, such as the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons and its Protocols; the Convention on Cluster Munitions and the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines;

- Reduce military expenditures, renew efforts to limit conventional arms and increase investment in prevention and social infrastructure and services, with a strong focus on redressing gender inequalities and structural marginalization, to buttress sustainable peace and steer societies back towards implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals;

- Request the Secretary-General to prepare an updated study on the social and economic impact of military spending;

- Stop the use by terrorist and other non-State armed groups of improvised explosive devices.

Small arms and light weapons and their ammunition are the leading cause of violent deaths globally, in conflict and non-conflict settings alike. As recognized in my Agenda for Disarmament, their proliferation, diversion and misuse undermine the rule of law, hinder conflict prevention and peace- building, enable criminal acts, including terrorist acts, human rights abuses and gender-based violence, drive displacement and migration and stunt development. Regulatory frameworks and policy measures are essential, but insufficiently implemented. Addressing factors that can affect their demand will also be important.

Recommendations

- Strengthen, develop and implement regional, subregional and national instruments and road maps to address challenges related to the diversion, proliferation and misuse of small arms and light weapons and ammunition.

- Set national and regional targets and measure progress toward the implementation of regulatory frameworks, including via data collection and monitoring.

- Pursue whole-of-government approaches that integrate small arms and light weapons control into development and violence reduction initiatives at the national and community levels, as well as in the national prevention strategies proposed under action 3.

STRENGTHENING PEACE OPERATIONS AND ADDRESSING PEACE ENFORCEMENT

ACTION 8: STRENGTHEN PEACE OPERATIONS AND PARTNERSHIPS

Peace operations – peacekeeping operations and special political missions – are an essential part of the diplomatic toolbox of the Charter of the United Nations. From special envoys working to broker peace agreements and regional offices that serve as forward platforms for preventive diplomacy to multidimensional peacekeeping operations, these missions will remain a central component of the continuum of United Nations responses to some of the most volatile peace and security contexts of today. Peace operations help operationalize diplomacy for peace by allowing the Organization to mount tailored operational responses, including by mobilizing and funding Member State capacities and capabilities that no single actor possesses.

Peacekeeping represents effective multilateral- ism in action, built on a partnership of all countries coming together to support the most vulnerable who are under threat. It brings Member States closer to the United Nations and gives those who deploy their troops and police a direct stake in our collective security. Since its conception 75 years ago, peacekeeping has continuously adapted to an ever-growing set of mandated tasks, ranging from the preservation of ceasefires to the protection of countless civilians from violence and abuse – achieving positive results despite challenges and limitations.

That said, in a number of current conflict environments, the gap between United Nations peace- keeping mandates and what such missions can actually deliver in practice has become apparent. The challenges posed by long-standing and unresolved conflicts, without a peace to keep, driven by complex domestic, geopolitical and transnational factors, serve as a stark illustration of the limitations of ambitious mandates without adequate political support. To keep peacekeeping fit for purpose, a serious and broad-based reflection on its future is required, with a view to moving towards nimble adaptable models with appropriate, forward-looking transition and exit strategies.

Recommendations

- For the Security Council, ensure that the primacy of politics remains a central tenet of peace operations: they must be deployed based on and in support of a clearly identified political process. The Security Council should provide its full support throughout, with active, continuous and coherent engagement with all parties.

- For the Security Council, not to burden peace operations with unrealistic mandates. Mandates must be clear, prioritized, achievable, sufficiently resourced and adapted to changing circumstances and political developments.

- For the Security Council and the General Assembly, undertake a reflection on the limits and future of peacekeeping in the light of the evolving nature of conflict with a view to enabling more nimble, adaptable and effective mission models while devising transition and exit strategies, where appropriate. This should clearly reflect the comparative strengths and successes of peacekeeping, as well as its doctrinal and operational limitations, as a tool that relies on strategic consent and the support of critical parties.

- Peace operations must be significantly more integrated and should leverage the full range of civilian capacities and expertise across the United Nations system and its partners, as part of a system of networked multilateralism and strengthened partnerships.

- In peace operations, fully leverage the use of data and digital technologies to effectively track conflict trends, understand local sentiment, enable inclusive dialogue, monitor impact and help guide evidence-based decisions. To this end, build on the strategy for the digital transformation of peacekeeping and critical innovations in mediation, good offices and peacemaking, in line with the Quintet of Change39See www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/09/un_2.0_-_quintet_of_change.pdf towards a United Nations 2.0 and the recommendations contained in action 2.

- Exit strategies and transitions from peace operations need to be planned early and in an integrated and iterative manner to achieve successful mission drawdowns and ensure that gains are consolidated and the risk of relapse into conflict or escalation is minimized.

- Renew their support and recommit to further peacekeeping reform that builds on the progress achieved through the Action for Peacekeeping initiative and the reform of the United Nations peace and security pillar. These efforts must make peacekeeping operations more versatile, nimble and adaptable.

ACTION 9: ADDRESS PEACE ENFORCEMENT

The increasing fragmentation of many conflicts, and the proliferation of non-State armed groups that operate across borders and use violence against civilians, has increased the need for multinational peace enforcement and counter-terrorisand counter-insurgency operations. Member States should urgently consider how to improve such operations and related aspects of the national and international response to evolving threats.

Recommendations

- For the Security Council, where peace enforcement is required, authorize a multinational force, or enforcement action by regional and subregional organizations.

- Accompany any peace enforcement action by inclusive political efforts to advance peace and other non-military approaches such as disarmament, demobilization and reintegration, addressing main conflict drivers and related grievances. Avoid actions that cause harm to civilian life, violate human rights, reinforce conflict drivers or the ability of violent extremist groups to increase recruitment.

- When countries or regional organizations willing to conduct peace enforcement lack the required capabilities, provide support to those operations directly. Peace enforcement action authorized by the Security Council must be fully in line with the Charter of the United Nations and international humanitarian and human rights law and involve effective and transparent accountability measures, including to the Security Council.

- In counter-terrorism contexts, ensure accountability and justice, including by advancing prosecution, rehabilitation and reintegration strategies. Make available appropriate expertise to support counter- terrorism operations through the creation of strategic action groups with support from the United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Coordination Compact, backed as needed by Member State contributions.

ACTION 10: SUPPORT TO AFRICAN UNION AND SUBREGIONAL PEACE SUPPORT OPERATIONS

The proliferation of non-State armed groups that operate across borders has presented a major and growing threat in several regions of Africa, as have other conflict drivers and crises related to the interlocking threats described above. This calls for a new generation of peace enforcement missions and counter-terrorism operations, led by African partners with a Security Council mandate under Chapters VII and VIII of the Charter of the United Nations, with guaranteed funding through assessed contributions. Decisions on this are long overdue, and progress must be made. The importance of these operations as part of the toolkit for responding to crises in Africa, alongside the full range of available United Nations mechanisms, is evident and the case for ensuring that they have the resources required to succeed is clear. This is the case for operations across the full spectrum from preventive deployments to peace enforcement.

Recommendations

- For the Security Council and General Assembly, ensure that operations authorized under Chapters VII and VIII of the Charter of the United Nations have the required resources to succeed, including assessed contributions where required. Requests related to African Union and subregional organizations’ peace support operations should be considered in a more systematic manner and no longer be considered exceptional.

NOVEL APPROACHES TO PEACE AND POTENTIAL DOMAINS OF CONFLICT

ACTION 11: PREVENT THE WEAPONIZATION OF EMERGING DOMAINS AND PROMOTE RESPONSIBLE INNOVATION

New technologies have the potential to transform the nature of conflict and warfare, putting human beings at increasing risk. The ease with which they can be accessed by non-State actors, including terrorist groups, poses a major threat. They raise serious human rights and privacy concerns, owing to issues such as accuracy, reliability, human control and data and algorithmic bias. The benefits of new and emerging technologies cannot come at the expense of global security. Governance frameworks, at the international and national level must be deployed to mini- mize harms and address the cross-cutting risks posed by converging technologies, including their intersection with other threats, such as nuclear weapons.

Tackling the extension of conflict and hostilities to cyberspace

The urgency of efforts to protect the safety and security of cyberspace has grown exponentially over the past decade, with a proliferation of malicious cyberincidents impacting infrastructure providing services to the public and critical to the functioning of society. Non-State actors, including terrorists, are also active in cyberspace. Cyberspace is not a lawless domain: States have affirmed that the Charter of the United Nations and international law apply to cyberspace (see A/77/275). Concrete progress at the multilateral level, as a result of work undertaken under the auspices of the General Assembly over the past two decades, has led all States to agree to be guided in their use of information and communications technologies by specific norms of responsible State behaviour. However, additional action is needed, and States should take concrete measures to prevent the extension and further escala- tion of conflict to the cyberdomain, including to protect human life from malicious cyberactivity.

Recommendations