A Global Digital Compact – an Open, Free and Secure Digital Future for All | Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 5

2023

Introduction

Chapeau

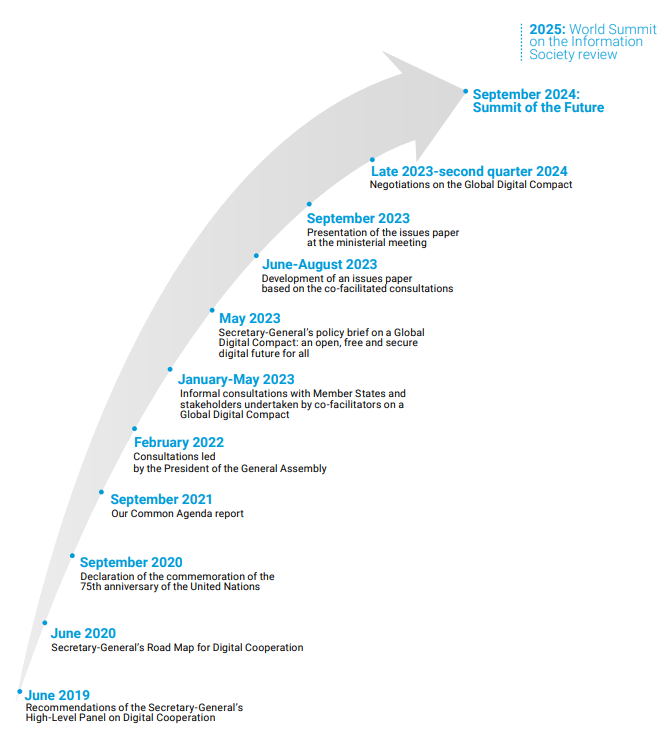

The challenges we face can only be addressed through stronger international cooperation. The Summit of the Future in 2024 is our opportunity to agree on multilateral solutions for a better tomorrow, strengthening global governance for both present and future generations (A/RES/76/307). The Secretary-General is invited to provide inputs to the preparations for the Summit in the form of action oriented recommendations, building on the proposals in the Our Common Agenda (A/75/982) report, which was itself a response to the UN75 Declaration (A/RES/75/1). This policy brief is one such input. It elaborates on the ideas first proposed in Our Common Agenda, taking into account subsequent guidance from UN Member States and intergovernmental and multi-stakeholder consultations, and rooted in the purposes and principles of the UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and other international instruments.

Purpose of this policy brief

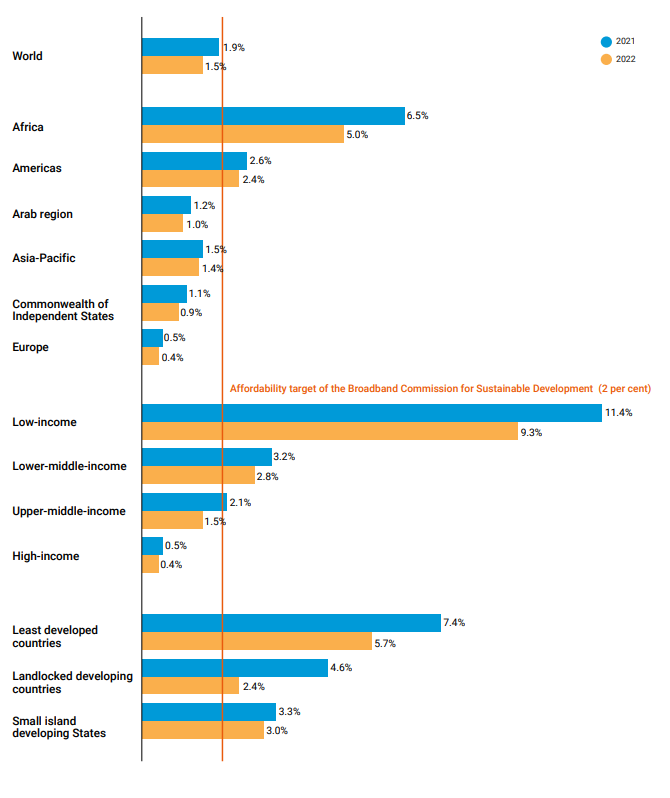

Our digital world is one of divides. In 2002, when governments first recognized the challenge of the digital divide, one billion people had access to the Internet. Today, 5.3 billion are digitally connected. Yet the divide persists across regions, gender, income, language and age groups. 89 percent of people in Europe are online, but only 21 percent of women in low-income countries use the Internet.1See International Telecommunication Union (ITU), Measuring digital development: Facts and Figures 2022 (Geneva, 2022). Digitally deliverable services now account for almost two-thirds of global services trade yet in some parts of the world access is unaffordable. The cost of a smart phone in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa is more than 40% of average monthly income and African users pay more than three times the global average for mobile data.2See International Telecommunication Union (ITU), Measuring digital development: Facts and Figures 2022 (Geneva, 2022). Less than half the world’s countries track digital skills and the data that exists highlights the depth of digital learning gaps.3See Wiley, Digital Skills Gap Index 2021 (New York, Wiley & Sons, 2021), white paper. Available at https://dsgi.wiley.com/download-white-paper.

Two decades since the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), the digital divide is still a gulf.

Data divides are also growing. As data is collected and used in digital applications it generates huge commercial and social value. While monthly global data traffic is forecast to grow more than 400 per cent by 2026, activity is concentrated among a few global players.4See United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), Industrial Development Report 2020: Industrializing in the digital age (Vienna, UNIDO, 2020). Many developing countries are at risk of becoming mere providers of raw data, while having to pay for the services that their data helps to produce.

The innovation divide is even more stark. Digital technologies have moved beyond the Internet and mobile devices into autonomous intelligent systems and networks, generative artificial intelligence (AI), virtual and mixed reality, distributed ledger technologies (such as blockchains), digital currencies and quantum technologies. The wealth generated by these innovations is highly unequal, dominated by a handful of big platforms and States.5The United States and China account for half of the world’s hyperscale data centres, 70 per cent of global AI talent and almost 90 per cent of the market capitalization of the world’s largest digital platforms. See United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Digital Economy Report 2021 (UNCTAD/DER/2021).

Inequality is rising. Enormous investments in technology have not been accompanied by spending on public education and infrastructure. Digital technology has led to massive gains in productivity and value. But these benefits are not resulting in shared prosperity.6See Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, Power and progress: our thousand-year struggle over technology and prosperity (New York, Hachette Book Group, 2023). The wealth of the top 1% is growing exponentially: between 1995 and 2021, they accounted for 38% of the increase in global wealth, while the bottom 50% took 2%.7See Lucas Chancel and others, World Inequality Report 2022 (World Inequality Laboratory, 2021). Digital technologies are accelerating the concentration of economic power in an ever smaller group of elites and companies: the combined wealth of tech billionaires, $2.1 trillion in 2022, is greater than the annual GDP of more than half of the G20 economies.8See Forbes, “Here are the richest tech billionaires 2022”, 5 April 2022.

Behind these divides is a massive governance gap. We lack even basic guardrails in new technologies. It is harder to bring a soft toy to markets today than an AI Chatbot. Because such digital technologies are privately developed, governments are constantly playing catch up to regulate them in the public interest. Decades of underinvestment in state capacities means that public institutions in most countries are ill equipped to assess and respond to digital challenges. Very few can compete with private actors to harness talent and offer incentives to digitally skilled people to work in the public sector. We are hollowing out public administrations at a time when they are most needed to support safe and equitable digital transformations.

As we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of digital technologies has brought unparalleled opportunities for how we live, learn, work and communicate. It has also brought great harm through irresponsible and malicious use and criminal abuses, as well as negative unintended consequences and environmental impacts. With states vying for political and military advantage through technological dominance, the risks of destabilizing competition, escalation or accidents mount. Even as societies grapple with these threats, newer technologies are raising fundamental questions for the features that make humans unique.

FIGURE I

DISPARITIES IN AFFORDABILITY OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY SERVICES WORLDWIDE (2022)

Data-only mobile broadband (2GB) basket prices as percentage of gross national income per capita,

2021-2022.

Source: International Telecommunication Union, affordability of ICT services. Available at www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/2022/11/24/ff22-affordability-of-ict-services

We urgently need to find ways to harness digital technologies for the benefit of all. We need national and international governance arrangements that prevent their misuse. We must shape innovation in ways that reflect universal human values and protect our planet. Unilateral regional, national or industry actions are insufficient: this cooperation must be global and multistakeholder to prevent digital inequalities becoming irreversible global chasms.

I propose the development of a Global Digital Compact that would set out principles, objectives and actions to advance an open, free, secure and human-centred digital future, one that is anchored in universal human rights and that enables the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals.

I outline three areas where the need for multistakeholder digital cooperation is urgent. I set out how a Global Digital Compact can help realize the UN75 Declaration’s commitment to ‘shaping a shared vision on digital cooperation’ by providing an inclusive global framework. Such a framework is essential for the multistakeholder action required to overcome digital, data and innovation divides and the governance essential for a sustainable digital future.

What does a shared vision on digital cooperation involve?

Closing the digital divide and advancing the Sustainable Development Goals

We have already set ambitious goals for universal and meaningful connectivity. The 2022 Kigali Declaration, agreed at the ITU World Telecommunication Development Conference, details what that involves: available, interoperable, quality and sustainable infrastructure, inclusive, affordable and secure coverage, as well as the capacity and skills for people to make full and safe use of connectivity. At the Transforming Education Summit of September 2022, 90 percent of the 133 national commitments referenced digital learning and skills. Follow-up actions include initiatives to expand public digital learning opportunities to make free and open education resources accessible to teachers, learners and families in rural as well as urban communities.9See www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/report_on_the_2022_transforming_education_summit.pdf

Concerted action is now needed to connect the remaining 2.7 billion of the global population, more than 1 billion of which are children and most of whom live in least developed countries (LDCs); policy and financial investments to make broadband and mobile devices affordable and reliable; and a global effort to strengthen digital learning and skills, with targeted efforts for women, girls and youth, so that people can take full advantage of the opportunities of connectivity and employers and workers can adapt to digital transformation.

Supply side initiatives are not enough for a human-centered digital transformation. A demand pull is also needed through the provision of digital public goods and services that are meaningful for people and communities. Governments, including in the G20 context and multistakeholder partnerships, such as the Digital Public Goods Alliance, are exploring options to develop digital public infrastructure. These public goods harness huge amounts of data that, if safely governed and effectively used, can help countries leapfrog their development and accelerate Agenda 2030. To enable schools, medical facilities, businesses and cultural institutions to pool resources and draw on public data, digital public infrastructure must be open, inclusive, secure and interoperable. The capacities of public administrations to manage and provide digital services must be urgently built.

As societies invest in these goods, a wealth of knowledge, best practice and experience is being gathered. The task before us now is to create common frameworks and standards for digital public infrastructure and services, build multistakeholder partnerships to scale up their provision and ensure that people and public servants have the skills and opportunities to use and create value from digital technologies.

We must also nurture innovation for development in areas where we are falling behind. We know digital technologies’ cross-cutting potential to advance progress across the SDGs beyond quality education (SDG 4) and industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9).

What we have not yet done is harness data at scale, make it globally accessible and use it to inform national and international development plans and programmes, as well as public private partnerships, e-commerce, tech entrepreneurship and capital investments. Progress towards achieving 41% of the 92 environmental SDG indicators, for example, cannot currently be globally measured due to a lack of interoperable data and standardized reporting. Overcoming this fragmentation and adopting global environmental data standards are critical to enable action to address the triple planetary crisis. Networks, such as the UNEP-facilitated Coalition for Digital Environmental Sustainability (CODES), can help promote common sustainability standards and access to environmental data, and align incentives to accelerate green transitions. Urgent investments are needed in ‘data commons’, which pool data and digital infrastructure across borders, build flagship datasets and standards for interoperability and bring together data and AI expertise from public and private institutions to build insights and applications for the SDGs.

FIGURE II

GLOBAL DIGITAL COOPERATION AND THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

Digital IDs linked with bank or mobile money accounts can improve the delivery of social protection coverage and serve to better reach eligible beneficiaries. Digital technologies may help to reduce leakage, errors and costs in the design of social protection programmes.

Drone technology can monitor crops and provide information on how much water is needed. Software systems available through mobile apps can monitor and analyse data to help farmers to decide when to plant, fertilize, irrigate and harvest their crops

Novel platform-based vaccine technologies and smart vaccine manufacturing techniques help to produce greater numbers of higher-quality vaccines. Open-source platforms can help accelerate and scale up vaccine delivery.

Accessible and affordable connectivity allows young people to use open, free and high-quality digital skills and training platforms. Smart digital platforms can be made accessible in local languages and used to align curricula with internationally recognized standards and certification.

Connectivity enables women and girls to access information and communicate for their safety and development. It can allow girls to access support services, learn about sexual and reproductive health and express their voices.

Internet of things-based precision irrigation and leakage management systems enable the monitoring and management of water resources. In urban areas, artificial intelligence systems draw upon data such as rain forecasts and the number of rooftops to determine rainfall run-off.

Next-generation digital networks have lower energy consumption, and smart grids can support electrification and more affordable connectivity. Artificial intelligence technology can be used for predictive maintenance of electrical utilities, enabling automatic backups and limiting downtime.

Internet availability leads to more jobs. Labour force participation and wage employment increase in areas with Internet availability. Use of local-language videos and decision support applications on smartphones supports personalized advice resulting in better jobs

Mobile digital technologies are enabling high-quality communications infrastructure and networks to expand into underserved remote and rural areas. Data and artificial intelligence technologies can accelerate innovation and productivity in key sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing.

Digital public goods and applications such as mobile money are enabling access to financial and other services for all members of societies, including women and girls, rural communities and displaced people.

Intelligent systems deploy information from remote sensors to guide traffic signals and maximize the efficient flow of commuters in urban areas. They can be used to design safe transportation for vulnerable and underserved communities.

Digital technologies such as 3D printing, the Internet of things, big data, cloud computing and blockchain can support a circular economy and supply chain resilience, in particular in manufacturing industries.

Information and communications technology solutions can help to cut nearly 10 times more carbon dioxide than they emit. Digital technologies combined with ecological design can help to reduce natural resources and other materials used in products by up to 90 per cent, lessening the impact of material extraction.

Satellite imaging and machine learning can help find and collect the 5 trillion pieces of ocean plastic trash. Online portals and mobile-based tools can connect the plastics supply chain, track the flow of waste materials, and help create transparent digital marketplaces for plastic waste.

Sensors and monitors connected to the Internet of things, cloud-based data platforms, blockchain-enabled tracking systems and digital product passports unlock new capabilities for the measurement and tracking of environmental and social impacts across value chains.

Public technologies and e-government services, where well designed and applied, enable people to access public services, reduce waste and corruption and create data that allow public institutions to target needs more effectively.

Partnerships between States, private sector and civil society leverage the capacity of digital tools to provide solutions for development across the Sustainable Development Goals. Examples include the Digital Public Infrastructure Alliance, the Coalition for Digital Environmental Sustainability and public-private partnerships for disaster response.

Making the online space open and safe for everyone

We have committed to applying human rights online and to specific measures to protect people and communities, especially women, children, youth and older persons, persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples, ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities. Yet in every society around the world harm is rampant. Open, safe and secure use of the Internet is slipping – potentially permanently – away from us.

Government shutdowns of the Internet, data-fueled state surveillance and predatory business models pose serious risks to human rights. Disinformation, hate speech, malicious and criminal activity in cyber space raise the risks and costs for everyone online.

UN processes addressing cyber security have identified norms of responsible state behaviour to help safeguard cyber peace and security and are exploring confidence and capacity building measures to advance them. States are also exploring legally-binding arrangements to tackle criminal threats as well as capacity for governments and judiciaries to counter, investigate, prosecute and adjudicate cybercrime. Regions and states are putting in place legislation for online safety. Some digital platforms are investing resources to better detect and respond to online abuse and curricula are being introduced to build digitally literate citizens capable of thinking critically and taking protective action.

Yet these approaches are proving insufficient to address harms. The onus for safety should not lie with users. Profiting from online presence and users’ data must not become a race to the bottom of corporate responsibility. We need transparency, accountability, oversight and capacities to make the online space open, safe and secure. As the High level Advisory Body on Effective Multilateralism has also emphasized, this must be a collective effort to ensure that regional, national or industry initiatives, however well-meaning, do not further fragment the Internet.

Action in four areas is essential.

First, we must balance the incentive for governments and industry to maximize data collection with principles and standards for policies and practices that protect data and the right to privacy. Personal data should only be collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes and its processing must be relevant and limited to what is necessary for them. People need to be able to control their personal data and how it is used. Public and commercial digital platforms need to enable meaningful opt in and out choices and people need the knowledge and skills to use them.

Second, we must apply the same safe design approaches and standards that we use across physical industries – cars, food, pharmaceuticals, toys – to digital technologies and platforms. Developing a shared understanding of what constitutes physical and mental harm based on universal human rights, and aligning safety standards across regions, countries and industry, can help build a global culture of digital trust and security. Ethics and safety teams cannot be an optional add on: technology companies must invest in standing capacities for responsible development and risk management.

Third, we must strengthen accountability for harmful and malicious acts online. The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights provide a framework to assess risks, mitigate and provide remedy for harm when necessary. As my forthcoming Policy Brief on Information Integrity on Digital Platforms highlights, given the transnational nature of digital platforms, transparency and safety measures must be interoperable; prompt redressal should not be the privilege of a few.

Fourth, we must protect the global nature of the Internet and the physical infrastructure that underpins it. 10For example, new undersea cables, which promise to connect more than 1.4 billion Africans, are owned by a handful of commercial actors.

The Internet is governed by long-established multistakeholder institutions. While legal and regulatory approaches may differ among jurisdictions, concerted effort must be made to maintain active policy compatibility and interoperability of the Internet.

Governing AI for humanity

The pace of digital technology development is challenging our governance systems. Tools that worked well in the past – public policy processes and legislation – are too siloed to anticipate and too slow to respond to the multiple ways in which innovations impact us.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) developments show how dangerous this governance gap has become. Companies are racing to bring AI technology to the marketplace before outputs are explainable and reliable and before their consequences are comprehensively assessed. Education is being transformed overnight. The ability to create believable content at scale and at low cost is intensifying misinformation and disinformation threats. Jobs may shift abruptly without sufficient time for institutions to adapt. States may be incentivized to develop and deploy AI-enabled systems for data collection, judicial proceedings, surveillance and warfare without the guardrails in place to ensure it is lawful. Introducing autonomy into weapon systems without human accountability and control may lead us into unchartered waters in international security. The potential for escalation and for global harms that we cannot mitigate is urgent.

AI holds immense potential for our economies, societies and planet. Applied well, AI can help resource efficiency, climate mitigation, disaster response and productive economic transformation. We are beginning to realize the scale of its disruptive potential, positive and negative but. we have yet to come together to consider the issue, much less collaborate to identify risks and agile ways of mitigating them.

I welcome the growing interest among AI experts on how best to govern the development and use of AI We need a global, multidisciplinary conversation to examine, assess, and align the application of AI and other emerging technologies. The over 100 sets of ethical AI principles that have been developed by different stakeholders share many common ideas, including the need for AI applications to be reliable, transparent, accountable, overseen by humans and capable of being shut down.11See UNESCO, Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence (UNESCO, Paris, 2022).

Available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381137. Different stakeholders are adapting or elaborating new frameworks for risk-management and redress. They need to be harmonised and effective across borders. Industry self-regulation is not enough. We need to bring stakeholders together in a meaningful effort to consider the implications of emerging technologies and ensure they align with universal human rights and values, before their widespread application in our societies, economies, militaries, and politics.

We also need to bend the arc of digital investments more towards solving societal problems and shared global challenges. Digital innovations, if consciously applied, can help overcome obstacles to SDG progress. But only if they rest on a diverse global base. Without engaging global talent and diverse and representative datasets, digital solutions will not achieve the scale we need to achieve the SDGs. And without involving public administrations, small and medium enterprises and communities in crafting locally relevant applications, they will not have the impact we seek.

A Global Digital Compact

Digital technologies today resemble natural resources such as air and water. Our wellbeing and development depends on their global availability. Their potential can be optimized only through shared access and use. Much as we are adapting our stewardship of energy and water in the climate crisis, we must collectively address the risk of digital-derived harms and maximize the potential for common good.

Some of the most crucial parts of the digital space already work this way. Internet protocols are managed through international frameworks and open standards. Much of the open-source software that enables them is community-stewarded. Information available on the Internet, such as the Digital Library of Commons, is provided through public networked arrangements. These public goods are not consistently global and they are vulnerable to harmful attacks and to neglect.

As the High-level Advisory Body on Effective Multilateralism notes, we have yet to put in place a global framework where states and non-state actors participate fully in shaping our shared digital space, and which promotes and supports interoperable governance across digital domains. Until we do so, our responses to digital challenges will be piecemeal, partial and off pace.

The UN is only one actor in this firmament. But it is the only global entity that can convene and facilitate the collaboration needed. The Organization must meet its responsibilities to support governments, companies, experts and civil society to engage effectively, through knowledge, data gathering, best practice sharing and where requested, technical assistance. It must lead by example in breaking down the silos of digital activity and building capacities across the three pillars of the Organization – peace and security, human rights and sustainable development.

Vision, purpose and scope

A Global Digital Compact would articulate a shared vision of an open, free, secure and human-centred digital future that rests on the purposes and principles of the UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The purpose of the Compact would be to advance multistakeholder cooperation to achieve this vision. It would articulate shared principles and objectives and identify concrete actions for their implementation. It would establish a global framework to bring together and leverage existing digital cooperation processes to support dialogue and collaboration by regional, national, industry and expert organizations and platforms, according to their respective mandates and competencies, and facilitate new governance arrangements where needed.

The Compact would be initiated and led by Member States with full participation of other stakeholders. Implementation would be open to all relevant stakeholders, including digital platforms, private sector actors, digital technology-focused coalitions and civil society organizations. Endorsement of the Compact’s principles and objectives and commitment to align respective policies and practice with them would be a requirement for participation in its implementation.

Objectives and actions

The Compact should set out principles and objectives for multistakeholder action. The principles set out in the 2005 Tunis Agenda and important multistakeholder processes since then offer a good basis on which to build.

FIGURE III

EXISTING PRINCIPLES RELEVANT TO A GLOBAL DIGITAL COMPACT

Sources: NETmundial Multistakeholder Statement; High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation; the Rights, Openness, Accessibility to all, Multi-stakeholder Participation principles of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; Tunis Agenda for the Information Society.

Objectives could be aligned with the broad objectives or themes being explored in jointly facilitated consultations. To support their practical implementation, the Compact should also identify achievable and measurable actions. Potential objectives and related actions could include the following objectives.

A. DIGITAL CONNECTIVITY AND CAPACITY-BUILDING

I propose the following objectives:

- Close the digital divide to connect all people, especially vulnerable groups, to the Internet in ways that are meaningful and affordable

- Empower people, through digital skills and capabilities, to participate fully in the digital economy, protect themselves from harm and pursue their physical and mental well-being and development

Accordingly, I propose the following actions:

Member States should:

- Commit to putting in place policies and new financial models to encourage telecommunications operators to bring affordable connectivity to hard-to-reach areas

- Commit to strengthening or instituting public education for digital literacy and transdisciplinary skills and to incentivize lifelong learning for workers

All stakeholders should:

- Agree to common targets for universal and meaningful connectivity and commit to track- ing progress against them

- Commit to extending the connectivity mapping and building currently being undertaken for schools to medical facilities and relevant public institutions

- Commit to coordinating actions, subsidies and incentives for digital technical and vocational training and public access facilities, in particular for women and girls and people living in rural areas

- Set the target of creating 1 million “digital champions” for the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, a quarter of them in Africa, by creating a capacity development network that leverages existing initiatives to pool training content, trainers and case studies, develop common competency frameworks and deliver a Digital for Sustainable Development Goals training standard

Multilateral organizations should:

- Set a revised target of $100 billion for pledges to the Partner2Connect Digital Coalition by 2030 (International Telecommunication Union)

- Accelerate efforts to connect all schools to the Internet by 2030 (Giga initiative of the International Telecommunication Union and the United Nations Children’s Fund)

B. DIGITAL COOPERATION TO ACCELERATE PROGRESS ON THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

I propose the following objectives:

- Make targeted investments in digital public infrastructure and services, and advance global knowledge and the sharing of best practices on digital public goods to serve as a catalyst for progress on the Sustainable Development Goals

- Ensure that data are a force multiplier for progress on the Goals by making data representative, interoperable and accessible

- Pool data, AI expertise and infrastructure across borders to generate innovations for meeting the Goal targets

- Develop environmental sustainability by design and globally harmonized digital sustainability standards and safeguards to protect the planet

Accordingly, I propose the following actions:

Member States should:

- Develop, with other stakeholders, a framework of design principles that are based on best practices, and a set of definitions for safe, inclusive and sustainable digital public infrastructure

- Build and maintain a global repository of experiences for digital public infrastructure and digital public services

- Allocate an agreed percentage of total international development assistance for digital transformation, with a particular focus on public administration capacity-building

All stakeholders should:

- Commit to completing the identification of gaps in Sustainable Development Goal data and make 90 per cent of Goal tracking data available and publicly accessible by 2030

- Commit to fostering open and accessible data ecosystems that enable earlier, faster and more targeted disaster mitigation and crisis response, including through the Complex Risk Analytics Fund of the United Nations and the Systematic Observations Financing Facility of the World Meteorological Organization

- Create collaborative research initiatives for data and AI applications for the Goals in priority areas such as agriculture, education, energy, health and green transitions

- Commit to building a global online resource of trusted and open environmental data for researchers and policymakers, together with the necessary licences, quality standards, infrastructure and safeguards to support green digital transformation

Multilateral and regional organizations should:

- Establish pooled financing mechanisms to support governments in planning and designing digital public infrastructure and services

- Expand voluntary purpose codes of the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in order to track and report financing for data and digital transformation across all development sectors and Sustainable Development Goals

- Utilize the common blueprint on digital transformations, to be devised by the United Nations as an end-to-end guide for digital development and as a tool for leveraging a new digital window in the joint Sustainable Development Goals trust fund to assist country-led digital transformation initiatives supported by resident coordinators and United Nations country teams

C. UPHOLDING HUMAN RIGHTS

I propose the following objectives:

- Make human rights the foundation of an open, safe and secure digital future, with human dignity at its core

- End the gender digital divide by ensuring that online spaces are non-discriminatory and safe for women and by expanding women’s participation in the technology sector and digital policymaking

- Apply international labour rights regardless of the mode of work and protect workers against digital surveillance, arbitrary algorithmic decisions and loss of agency over their labour

Accordingly, I propose the following actions:

Member States should:

- Commit to establishing a digital human rights advisory mechanism, facilitated by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, that would provide practical guidance on human rights and technology issues, building on the work of the human rights mechanisms and experts, showcase good practices and convene stakeholders to explore effective and coherent responses to legislative or regulatory issues

All stakeholders should:

- Commit to reflecting existing legal commitments in regional, national and industry policies and standards and take specific measures to protect and empower women, children, young people, older persons, persons with disabilities, Indigenous Peoples and ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities to fully benefit from digital technologies

- In the case of Governments, employers and workers, commit to upholding labour rights, supported by the International Labour Organization, and promote meaningful and equitable employment opportunities through innovative regulation, social protection and investment policies

D. AN INCLUSIVE, OPEN, SECURE AND SHARED INTERNET

I propose the following objectives:

- Safeguard the free and shared nature of the Internet as a unique and irreplaceable global public asset

- Reinforce accountable multi-stakeholder governance of the Internet to help harness its potential to advance the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals and leave no one behind

Accordingly, I propose the following actions:

Member States should:

- Commit to avoiding blanket Internet shutdowns, which run counter to efforts to close the digital divide, and ensure that targeted measures are proportional, non-discriminatory and undertaken only as necessary for transparently reported and legitimate aims and in accordance with international human rights law

- Commit, in the context of United Nations cyber-diplomacy processes, to refraining from actions that would disrupt, damage or destroy critical infrastructure that provides services across borders or the infrastructure that underpins the general availability and integrity of the Internet

All stakeholders should:

- Commit to upholding net neutrality, non-discriminatory traffic management, technical standards, infrastructure and data interoperability, and platform and device neutrality to support an open, interconnected Internet

E. DIGITAL TRUST AND SECURITY

I propose the following objectives:

- Strengthen cooperation across Governments, industry, experts and civil society to elaborate and implement norms, guidelines and principles relating to the responsible use of digital technologies

- Develop robust accountability criteria and standards for digital platforms and users to address disinformation, hate speech and other harmful online content

- Build capacity and expand the global cybersecurity workforce and develop trust labels and certification schemes as well as effective regional and national oversight bodies

- Mainstream gender in digital policies and in technology design and ensure zero tolerance for gender-based violence, in order to create a more equal and connected world for women and girls

Accordingly, I propose the following actions:

All stakeholders should:

- Commit to developing common standards, guidelines and industry codes of conduct to address harmful content on digital platforms and promote safe civic spaces, as follows:

F. DATA PROTECTION AND EMPOWERMENT

I propose the following objectives:

- Ensure that data are governed for the benefit of all and in ways that avoid harming people and communities

- Provide people with the capacity and tools to manage and control their personal data, including options and skills to opt in or out of digital platforms, and the use of their data for training algorithms

- Develop multilevel and interoperable standards and frameworks for data quality, measurement and use, in full respect of intellectual property rights, to enable safe and secure data flow and an inclusive global economy

Accordingly, I propose the following actions:

Member States and regional organizations should:

- Legally mandate protections for personal data and privacy, based on, for example, the African Union Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection and the European Union General Data Protection Regulation. Such protections could:

- Consider the adoption of a declaration on data rights that enshrines transparency, to ensure scrutable data-driven decisions, interoperability and portability, and protections against behaviour manipulation and discrimination

- Consider the call by the High-level Advisory Board on Effective Multilateralism to seek convergence on principles for data governance through a Global Data Compact in a new International Decade for Data

All stakeholders should:

- Commit to developing common definitions and data standards for interoperability, access to data according to type of data, and data quality and measurement and to their monitoring and enforcement

- Commit to enhancing agency and control by people over the use of their personal data, including opt-out choices, enhanced interoperability, data portability and encryption options

- Consider the recommendation by the High-level Advisory Board on Effective Multilateralism on the multi-stakeholder development of a Global Data Compact for adoption by Member States by 2030

G. AGILE GOVERNANCE OF AI AND OTHER EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES

I propose the following objectives:

- Ensure that the design and use of AI and other emerging technologies are transparent, reliable, safe and under accountable human control

- Make transparency, fairness and accountability the core of AI governance, taking into account the responsibility of Governments to identify and address the risks that AI systems could entail and the responsibility of researchers and companies developing AI systems to monitor, transparently communicate and address such risks

- Combine international guidance and norms, national regulatory frameworks and technical standards into a framework for agile governance of AI, with an active exchange of lessons learned and emerging best practices across borders, industries and sectors In the case of regulators, coordinate – across digital, competition, taxation, consumer protection, online safety and data protection policies as well as labour rights, to ensure the alignment of emerging digital technologies with our human values

Accordingly, I propose the following actions:

Member States should:

- Urgently launch, together with industry, a global collaborative research and development effort to ensure that AI systems are safe, fair, accountable, transparent, interpretable, trustworthy and aligned with human values. They should also consider mandating that a mini- mum percentage of investments in AI be allocated to AI governance and ensuring that AI systems are aligned with human values. In that respect, Member States should consider the recommendation by the High-level Advisory Board on Effective Multilateralism that a fund be developed to incentivize research and preparedness on the existential risks that could arise from ungoverned AI evolution

- Establish a high-level advisory body for AI within the framework of the Global Data Compact. This body could include Member State experts, relevant United Nations entities, industry representatives, academic institutions and civil society groups that would meet regularly to consider emerging regional, national and industry AI governance arrangements. It could offer perspectives on how ethical, safety and other regulatory standards could be aligned, interoperable and compliant with universal human rights and rule of law frameworks. The advisory body could publicly share the outcomes of its deliberations and, where relevant, offer recommendations and ideas on the governance of AI technologies, including options for internationally agreed measures and standards

- Agree with industry associations to develop sector-based guidelines in order to ensure that technology developers and other users have applicable, relatable guidance for the design, implementation and audit of AI-derived tools in specific settings. Relevant United Nations entities, such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization through its recommendation on the ethics of AI and the World Health Organization (WHO) through its Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: WHO guidance, could support stakeholders in developing sector-specific due diligence and impact assessments

- Commit, together with technology developers and digital platforms, to reinforcing transparency and accountability measures, including establishing human rights and ethics teams and transdisciplinary and independent oversight boards, documenting and reporting cases of harm caused by AI systems, sharing lessons learned and developing redressal measures

- Commit to building cross-domain and multistakeholder regulatory capacity in the public sector, including judicial capacity as noted by the High-level Advisory Board on Effective Multilateralism, to ensure that regulations and public procurement of systems based on AI and other emerging technologies advance inclusion, safety, security and the prompt addressing of risks as they arise

- Consider prohibitions on the use of technology applications whose potential or actual impacts cannot be justified under international human rights law, including those that fail the necessity, distinction and proportionality tests

H. GLOBAL DIGITAL COMMONS

I propose the following objectives:

- Develop and govern digital technologies in ways that enable sustainable development, empower people, and anticipate risks and harms and address them effectively

- Ensure that digital cooperation is inclusive and enable all relevant stakeholders to contribute meaningfully according to their respective mandates, functions and competencies

- Agree that the foundations of our cooperation are the Charter of the United Nations, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the framework of universally recognized human rights and international humanitarian law

- Enable regular and sustained exchange across States, regions, industry sectors and issues to support the learning of lessons and best practices, governance innovation and capacities and to ensure that digital governance is continuously aligned with our shared values

Accordingly, I propose the following actions:

All stakeholders should:

- Commit to sharing governance and regulatory experience, align international principles and frameworks with national measures and industry practices, improve regulatory capacity and develop agile governance measures to keep up with the rapid pace of technology

- Commit to taking forward the principles, objectives and actions set out in the Global Digital Compact through a framework for sustained, practical multi-stakeholder cooperation as described below

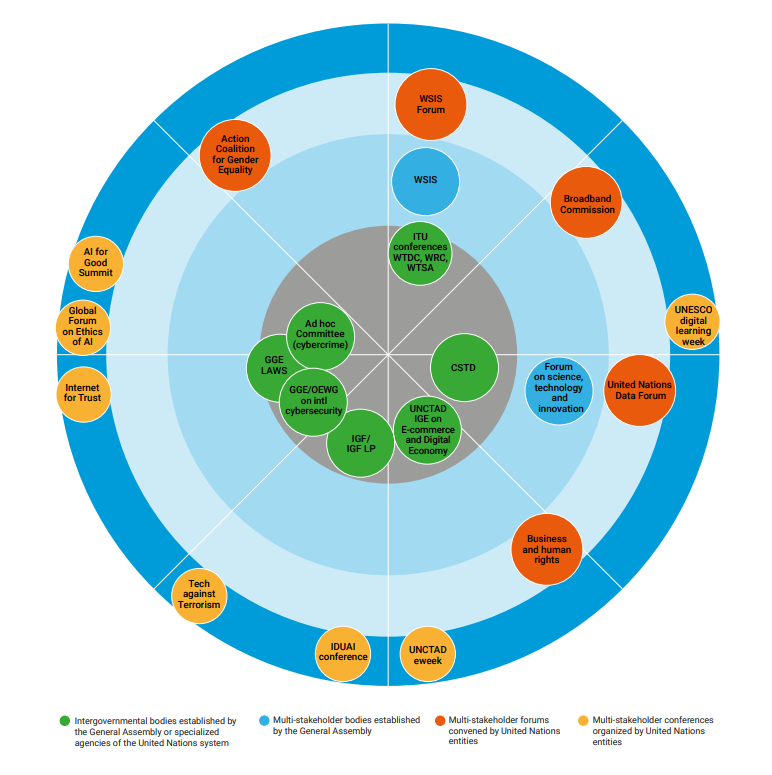

Implementation, follow up and review

The success of a Global Digital Compact will rest on implementation. Different stakeholders would be responsible for implementing the Compact at national, regional and sectoral levels taking into account regional contexts and respecting national policies, mandates and competencies. Existing cooperation mechanisms, especially the Internet Governance Forum and WSIS, as well as UN entities, including ITU, OHCHR, UNCTAD, UNESCO and UNDP, would play an important role in supporting implementation, providing issue and sectoral knowledge, guidance and practical expertise to facilitate dialogue and action on agreed objectives.

But these individual efforts must be underpinned by sustained, networked collaboration. Without this, we will not overcome the fragmented and irregular policy discussions that have characterized digital coordination to date. Without a transparent and accountable implementation framework, duplication of efforts will persist and policy and technical standard setting functions will continue to be blurred across forums. We need a networked multilateral arrangement that supports the establishment of converging agendas, facilitates communication across different work areas, incentivizes the participation of relevant policy actors and the alignment of norms and standards. Such a global framework is essential to support knowledge sharing, best practices and lessons learning on digital governance that can be translated into national and regional regulatory arrangements and industry standards. The High level Advisory Body on Effective Multilateralism has proposed the establishment of a global Commission on Just and Sustainable Digitalization to meet these objectives.

Multikstakeholder implementation

Digital technologies could be used to permit wider consultation, communication and information sharing, especially among civil society organizations. Opportunities for participation could be regularly reviewed so that the Compact implementation framework remains inclusive and keeps pace with technology developments.

Multistakeholder participation could be supported by a Trust Fund that could, inter alia, sponsor a Digital Cooperation Fellows programme and civil society participation, as well as the maintenance of a UN portal.12A Digital Cooperation Fellowship initiative could draw on the model of the United Nations Disarmament Fellowship Programme. To support young people’s input, my Envoys on Technology and on Youth could draw on the proposed UN Youth Town Hall.13See Policy brief 3 (A/77/CRP.1/Add.2)

A Digital Cooperation Forum

Regular convening of the Compact implementation framework would be essential to keep pace with technology developments. The Summit of the Future, in establishing a Global Digital Compact, could task me to convene an annual Digital Cooperation Forum to support tripartite engagement and follow up on Compact implementation.

The Digital Cooperation Forum would support Member States, private sector and civil society stakeholders, as the HLAB also recommends, to:

- Discuss and review implementation of agreed GDC principles and commitments.

- Facilitate transparent dialogue and collaboration across digital multistakeholder frameworks and reduce duplication of effort where relevant and appropriate.

- Support evidence-based knowledge and information sharing on main digital trends.

- Pool lessons learned and promote cross-border learning on digital governance.

- Identify and promote policy solutions to emerging digital challenges and governance gaps, and

- Highlight policy priorities for individual and collective stakeholder decision-making and action.

The Digital Cooperation Forum would accommodate existing forums and initiatives in a hub and spoke arrangement and help identify gaps where multistakeholder action is required. Existing forums and initiatives, many of which are listed in Annex 1, would support the translation of Compact objectives into practical action, within their respective areas of expertise. The Digital Cooperation Forum would help promote communication and alignment among them and focus collaboration around the priority areas set out in the Compact. Internet governance objectives and actions, for example, would continue to be supported by the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) and relevant multistakeholder bodies (ICANN and IETF). The recently-established IGF Leadership Panel, in accordance with its mandate to enhance the impact of these bodies, could share IGF outputs in the Compact implementation framework leveraging relevant expertise from the Multi-stakeholder Advisory Group (MAG) of the IGF.14See the terms of reference of the Internet Governance Forum Leadership Panel, available at www.intgovforum.org/en/content/terms-of-reference-for-the-igf-leadership-panel.

Actions proposed in this Policy Brief to address governance gaps could strengthen Compact implementation. Where relevant, they would support collaboration in priority areas, including in the preparation of the annual Digital Cooperation Forum. These include, for example, the Digital Human Rights Advisory Mechanism, and initiatives in support of digital public infrastructure and capacity development.

A hub and spokes arrangement would also help stakeholders to identify and address gaps in multistakeholder cooperation, such as international data and AI governance. The High-Level Advisory Body on AI, for example, would facilitate structured exchange of national and industry experiences to align AI development with human rights and values and to assist researchers and innovators with practical guidance on developing responsible and trustworthy AI.

To support the preparation of the agenda of the Digital Cooperation Forum, I would establish a tripartite Advisory Group, drawn from a diverse and representative group of state, non-state and UN participatory stakeholders, and building upon the experience of multistakeholder implementation of the Road Map on Digital Cooperation. Membership would rotate every two years to enable the participation of diverse stakeholders and benefit from wide skills and perspectives. Preparation of the Forum could also include regional consultations facilitated by UN regional economic commissions in cooperation with regional organizations, so that the priorities and perspectives of different regional contexts are reflected in the agenda and content of discussions. The commissions could also facilitate context-specific follow up and exchange.

The Digital Cooperation Forum would be informed by an annual report provided by my Envoy on Technology, building on input provided through a digital platform open to contributions from stakeholders and publicly accessible. The report would provide data-driven updates on progress across actions agreed in the Compact and resulting stakeholder initiatives. A live and accessible UN portal would provide a single entry point to access the wide range of UN data resources and tools now available on digital developments.

The Forum would be action-oriented, focused on assessing and communicating digital governance progress and gaps, facilitating peer learning and exchange and distilling – much faster than we do now – key trends and challenges in emerging technologies. It would catalyze practical efforts such as a potential global network of digital regulators cutting across regulatory domains.15One such example is the International Competition Network launched in 2001 in New York by antitrust officials from 14 jurisdictions. It would not seek to negotiate outcomes but rather to reflect, via accessible mapping, visuals and policy notes.16The International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development have a long-standing tradition of such policy briefs where progress is being made and where we need to go.

Conclusion

Almost four years have passed since the High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation published its report. More than two years have passed since the release of my Roadmap on Digital Cooperation and Our Common Agenda which outlined options for practical action to advance digital cooperation. The High Level Advisory Body has offered important new ideas. The time for talking about the need for digital cooperation has long passed. We need to focus on how we make this a reality. We need to act now, and with speed, if we are to recover the potential of digital technologies for the equitable and sustainable development that is slipping away from us and the planetary crisis that confronts us. We must work together if we are to restore the trust that unconsidered, irresponsible or malicious use has damaged in and among societies, the private sector and states. And we must commit to sustained follow up and review so that agreed principles and priorities are translated into practice and we do not retreat into siloed debates.

The ideas set out in this Policy Brief are neither exclusive nor exhaustive. They can provide a basis for discussion and debate in the consultations on the Global Digital Compact currently underway. The UN system stands ready to assist your deliberations in considering them and in exploring new ideas. Whatever directions we take, they must be towards concrete and meaningful multistakeholder action if we are not to leave our planet, people and our humanity behind.

FIGURE IV

TIMELINE OF THE GLOBAL DIGITAL COMPACT

Annex I: UN intergovernmental and multistakeholder digital cooperation bodies and forums

This list does not include UN programmatic initiatives to advance UN and/or multistakeholder cooperation in specific issue areas, for example, ITU’s Partner2Connect Digital Coalition to accelerate universal and meaningful connectivity in the hardest-to-connect communities.

1. Intergovernmental bodies established by the UN General Assembly or UN specialized agencies (listed alphabetically)

Ad Hoc Committee to Elaborate a Comprehensive International Convention on Countering the Use of Information and Communications Technologies for Criminal Purposes (since 2021); Commission on Science and Technology for Development (annual since 2006 to serve, inter alia, as the focal point for system-wide follow-up to the outcomes of the World Summit on the Information Society); Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security (six since 2004); ITU Plenipotentiary Conference and ITU conferences (every four years); World Radio communication Conference, World Telecommunication Development Conference and World Telecommunication Standardization Assembly; Group of Governmental Experts on Emerging Technologies in the Area of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems in the context of the objectives and purposes of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (since 2016); Open-ended Working Group on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security (2019– 2021); open-ended working group on security of and in the use of information and communications technologies (since 2021); United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Intergovernmental Group of Experts on E-commerce and the Digital Economy (since 2016).

2. UNGA-established multistakeholder bodies

Internet Governance Forum (annual, since 2005); multi-stakeholder forum on science, technology and innovation for the Sustainable Development Goals (annual since 2016 as part of the Technology Facilitation Mechanism; hosted by the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the Secretariat); World Summit on the Information Society, implementation, follow-up and review processes (every 10 years, since 2005).

3. Multistakeholder forums convened by UN entities

Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development to promote universal connectivity and its working groups (since 2010, hosted by ITU and UNESCO); Gender Equality Forum Action Coalition on technology and innovation for gender equality (since 2021, organized by UN Women); UN Forum on Business and Human Rights to promote dialogue and cooperation on business and human rights (since 2011, hosted by OHCHR under the guidance of a Working Group established by the Human Rights Council); WSIS Forum facilitating the implementation of the WSIS Action Lines for advancing sustainable development (since 2009, co-organised by ITU, UNESCO, UNDP and UNCTAD and the WSIS Action Lines Co-Facilitators); UN World Data Forum (since 2017, organized by DESA).

4. Selected multistakeholder conferences organized by UN entities

Artificial Intelligence for Good Global Summit (since 2017, organized by ITU and co-convened with Switzerland); Global Forum on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence (since 2022, UNESCO); International Forum on Artificial Intelligence and Education (since 2019, co-organized by UNESCO and China); Internet for Trust Conference (UNESCO in 2023); Tech against Terrorism (since 2017, Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate); UNCTAD eWeek (biennially since 2015); UNESCO digital learning week (since 2011); International Day for Universal Access to Information conference (since 2016, UNESCO).

5. Other multistakeholder platforms

Development to promote universal connectivity and its working groups (since 2010, hosted by ITU and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)); Action Coalition on Technology and Innovation for Gender Equality of the Generation Equality Forum (since 2021, organized by the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN-Women)); Forum on Business and Human Rights to promote dialogue and cooperation on business and human rights (since 2011, hosted by the Ofice of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights under the guidance of a working group established by the Human Rights Council); World Summit on the Information Society Forum facilitating the implementation of its action lines for advancing sustainable development (since 2009, co-organized by ITU, UNESCO, the United Nations Development Programme and UNCTAD and the action lines co-facilitators); United Nations World Data Forum (since 2017, organized by the Department of Economic and Social Affairs).

FIGURE V

UN INTERGOVERNMENTAL AND MULTI-STAKEHOLDER DIGITAL COOPERATION BODIES AND FORUMS

Abbreviations: AI, artificial intelligence; CSTD, Commission on Science and Technology for Development; GGE, group of governmental experts; IGE, intergovernmental group of experts; IDUAI, International Day for Universal Access to Information; IGF, Internet Governance Forum; LAWS, Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems; LP, Leadership Panel; OEWG, open-ended working group; WRC, World Radiocommunication Conference; WSIS, World Summit on the Information Society; WTDC, World Telecommunication Development Conference; WTSA, World Telecommunication Standardization Assembly

Annex II. Select UN documents on digital technologies

GENERAL ASSEMBLY

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights, resolution 217 A (III), December 1948

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, resolution 2200 A (XXI), December 1966

- Guidelines for the regulation of computerized personal data files, resolution 45/95, December 1990

- World Summit on the Information Society, resolution 56/183, December 2001

- Science and technology for development, resolution 58/200, December 2003 (and subsequent resolutions)

- The right to privacy in the digital age, resolution 68/167, December 2013 (and subsequent resolutions)

- Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, resolution 70/1, September 2015

- Outcome document of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the overall review of the implementation of the outcomes of the World Summit on the Information Society, resolution 70/125, December 2015

- Developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security, resolution 53/70, since 1998 (and subsequent resolutions)

- Impact of rapid technological change on the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals and targets, resolution 73/17, November 2018

- Information and communications technologies for sustainable development, resolution 76/189, December 2021

- Countering the use of information and communications technologies for criminal purposes, resolution 74/247, December 2019 (and subsequent resolutions)

- Declaration on the commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the United Nations,resolution 75/1, September 2020

- Follow-up to the report of the Secretary-General entitled “Our Common Agenda”, resolution 76/6, November 2021

- Effective promotion of the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities, resolution 76/168, December 2021

- Countering disinformation for the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, resolution 76/227, December 2021

- Strengthening national and international efforts, including with the private sector, to protect children from sexual exploitation and abuse, resolution 77/233, December 2022

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL

- Prevention, protection and international cooperation against the use of new information technologies to abuse and/or exploit children, resolution 2011/33, July 2011

- Socially just transition towards sustainable development: the role of digital technologies on social development and well-being of all, resolution 2021/10, June 2021

- Open-source technologies for sustainable development, resolution 2021/30, July 2021

- Assessment of the progress made in the implementation of and follow-up to the outcomes of the World Summit on the Information Society, resolution 2022/15, July 2022 (and previous resolutions since 2006)

- Science, technology and innovation for development, resolution 2022/16, July 2022

HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL

- Human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises, resolution 17/4, June 2011

- The promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet, resolution 20/8, July 2012 (and subsequent resolutions)

- The right to privacy in the digital age, resolution 28/16, March 2015 (and subsequent resolutions)

- Rights of the child: information and communications technologies and child sexual exploitation, resolution 31/7, March 2016

- Accelerating efforts to eliminate violence against women and girls: preventing and responding to violence against women and girls in digital contexts, resolution 38/5, July 2018

- New and emerging digital technologies and human rights, resolution 41/11, July 2019 (and subsequent resolutions)

- Freedom of opinion and expression, resolution 44/12, July 2020

- Human rights of older persons, resolution 48/3, October 2021

- Countering cyberbullying, resolution 51/10, October 2022

- Neurotechnology and human rights, resolution 51/3, October 2022

UNITED NATIONS TREATY BODIES

- Committee on the Rights of the Child, general comment No. 16 (2013) on State obligations regarding the impact of the business sector on children’s rights, April 2013

- Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, general recommendation No. 35 (2017) on gender-based violence against women, updating general recommendation No. 19, July 2017

- Committee on the Rights of the Child, general comment No. 25 (2021) on children’s rights in relation to the digital environment, March 2021

INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Plenipotentiary Conference, Constitution and Convention of the International Telecommunication Union, 1992

- Resolutions adopted at the ITU Plenipotentiary Conferences, most recently in 2022 in Bucharest

- Resolutions adopted at the World Radiocommunication Conferences, the next one to be held in Dubai in 2023

- Resolutions adopted at the World Telecommunication Standardization Assemblies, most recently held in 2022 in Geneva

- Resolutions adopted at the World Telecommunication Development Conferences, most recently held in 2022 in Kigali

- Radio Regulations and Revisions, Edition of 2020, World Radiocommunication Conferences

- International Telecommunication Regulations and the World Conference on International Telecommunications

UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION

- Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage, October 2003

- General Conference resolution 38 C/53 of 10 August 2015 endorsing the “ROAM” principles for Internet universality.

Declarations and recommendations

- Windhoek+30 Declaration: Information as a Public Good, April–May 2021

- Recommendation on the ethics of artificial intelligence, November 2021

- Recommendation on open science, November 2021

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME

- Promotion of activities relating to combating cybercrime, including technical assistance and capacity-building, Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice resolution 20/7, April 2011

- Strengthening international cooperation to combat cybercrime, Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice resolution 26/4, May 2017

- Improving the protection of children against trafficking in persons, including by addressing the criminal misuse of information and communications technologies, Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice resolution 27/3, May 2018

- Declaration adopted at the Fourteenth United Nations Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, A/CONF.234/16, March 2021

WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY

- Digital health, resolution 71.7, May 2018

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION

- Unified data policy, resolution 1, October 2021

WORLD SUMMIT ON THE INFORMATION SOCIETY (GENEVA AND TUNIS, 2003–2005)

- Geneva Declaration of Principles, WSIS-03/ GENEVA/DOC/0004

- Geneva Plan of Action, WSIS-03/GENEVA/ DOC/0005

- Tunis Commitment, WSIS-05/TUNIS/DOC/7

- Tunis Agenda for the Information Society, WSIS-05/TUNIS/DOC/6 (Rev.1)

Annex III: Consultations

This Policy Brief builds upon the foundation laid by the Report of the Secretary-General’s High level Panel on Digital Cooperation of June 2019, the Secretary-General’s Road Map on Digital Cooperation of June 2020 and the Report of the Secretary-General entitled Our Common Agenda (A/75/982).

It has benefitted from interaction with different stakeholders representing governments, international organizations, civil society, including academia and youth, private sector, and the technology community. These consultations and meetings were held over nine months between June 2022 and March 2023 in person in Barcelona, Berlin, Brasilia, Brussels, Bucharest, Doha, Geneva, Kigali, Mexico City, Nairobi, New Delhi, New York, Riyadh, Tokyo, Valletta and Vienna as well as online.

The following UN entities contributed inputs – DESA, ILO, ITU, the Office of the Special Envoy on Youth ,OHCHR, UN Women, UNCTAD, UNDP, UNESCO, UNDP, UNEP, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIDO, UNODA, UNODC, WFP, WIPO, WHO and WMO. More than eighty stakeholders submitted inputs and forty supplementary documents online. The IGF Leadership Panel’s inputs have also informed the Policy Brief.