How the theory of ‘good governance’ failed in practice

Twenty years ago, ‘good governance’ became the buzz-word among theoreticians of economic development. The assumption was that, once in place, good government would lead the drive toward national development. Mick Moore has recently offered a rather sceptical assessment of the latest in this line of development theories .

At the time, it was argued that better governance would naturally follow once states became more democratic, more accountable, more transparent, and more firmly bound by the rule of law. Disagreements soon emerged over the ‘core content’ of good governance, and the list of expectations became increasingly expansive. Questions about timing and sequencing were brushed aside with the formula: ‘the faster the better’ – a kind of shock-and-awe approach. Little thought was given to how local elites – including bureaucracies – might respond (see Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy by Daniel P. Carpenter). These actors may have had their own agendas, or they may have skilfully redirected the structural reform programme to serve partisan interests (see Politics in Time by Paul Pierson).

On the way to meet reality, the theory lost some of its spots (and relevance). One began to speak of good enough governance‘, ‘political settlements’, and ‘working with the grain’. These less ambitious goals made perfect sense as ‘second best solutions’. The main problem from the point of view of theory is that ‘good enough’ and similar terms describe unique and incommensurable compromises – they do not mark linear and stately progress toward the eutopia of good governance. In my youth, one called it disparagingly ‘muddle through’. So what is the point of wasting time on theory – unless it is to focus attention on the obvious, at the expense of context?

Why the West is obsessed with theory

Why our Western passion for ‘theory’? Theory appears all over the place and creeps into the analysis of social reality. I am reading Neil Gross’s biography of Richard Rorty. This work is wrapped around a ‘theory of self-affirmation’, which purports to explain the philosopher’s emergence. The conclusion identifies twelve ‘theoretical propositions’ that have emerged from the study. One homely sentence would have sufficed: Rorty was an ambitious young man.

In the introduction, the author writes: ‘I believe the social-scientific research enterprise must encompass two interrelated but distinct phases: a phase of theory building, in which the goal is to develop theories about the mechanisms generative of particular outcomes, and a phase of systematic empirical investigation, in which an attempt is made to assess the causal significance of the theorised mechanisms across a large number of cases.’ This apes the differentiation between theoretical and experimental physics and ignores the (to me self-evident) fact that cause–effect relationships in the physical world are intrinsically different from those prevailing in social reality.

The term ‘mechanism’ has been emphasised to show what is, for me, a baffling view of the social world as akin to a Copernican system. This position is predicated on the view that necessary conditions – rather than enablers – drive the social world. Once these conditions are in place, the rest can be derived – so the topos.

Here is a quote from an unimpeachable philosopher, Friedrich Hayek (see Individualism & Economic Order by Friedrich Hayek):

‘There is an essential distinction […] between a permanent legal framework so devised as to provide all the necessary incentives to private initiative to bring about the adaptations required by any change and a system where such adaptations are brought about by central direction.’

The necessary legal framework drives private initiative, which is a sufficient, albeit subordinate, cause once the necessary conditions are in place. (Just for the record: in Philosophical Investigations, Ludwig Wittgenstein rejected this separation, but his insights do not seem to have percolated far). Structure drives function. The necessary legal framework drives private initiative, which is a sufficient, albeit subordinate, cause once the necessary conditions are in place.

How Confucian thought offers a relationship-based alternative

Beyond truth and usefulness: Is this really the only way forward?

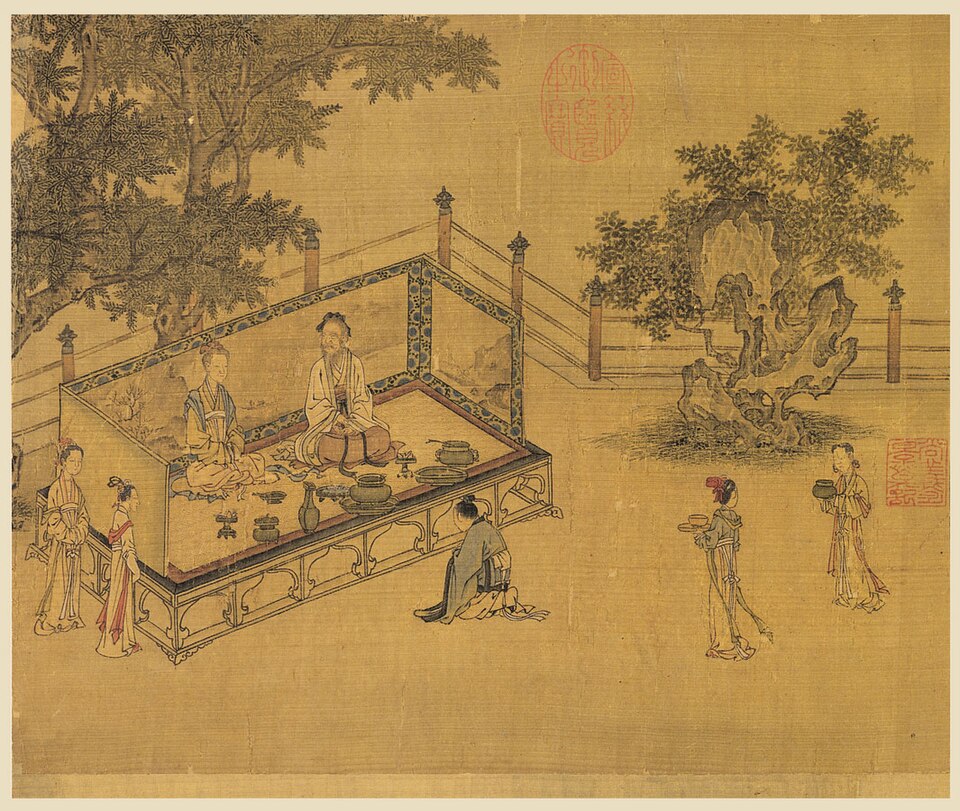

Now contrast this Western faith in abstract mechanisms with the Confucian emphasis on relationship and reverence – expressed through the concept of xiao, or family reverence. As The Chinese Classic of Family Reverence (Henry Rosemont Jr. and Roger T. Ames) explains: ‘It is family reverence (xiao) that is the root of excellence, and whence education (jiao) is born.’

Family reverence begins with protecting the body received from one’s parents and culminates in moral distinction, public service, and honour for one’s family name. Proper behaviour is anchored not in structure but in intention, responsibility, and personal conduct.

A passage from the same text illustrates how family reverence once sustained broader order:

‘Of old when enlightened (ming) kings used family reverence to bring proper order to the empire, they would not presume to neglect the ministers of the smallest state, how much less so the dukes, earls, and other members of the high nobility. Thus all of the different vassal states participated wholeheartedly in their service to these former kings. Those who would bring proper order to the vassal states would not presume to ignore the most dispossessed, how much less so the lower officials and common people. Thus the various families all participated wholeheartedly in their service to these former lords. Those who would bring proper order to the various families would not presume to overlook their servants and concubines, how much less so their wives and children. Thus all the people participated wholeheartedly in their service to the parents. In such a world, the parents while living enjoyed the comforts that parents deserve, and as spirits after death took pleasure in the sacrificial offerings made to them.’

Hence the empire was peaceful (he) and free of strife, natural disasters did not occur, and man-made calamities were averted. In this way the enlightened kings used family reverence to bring about order to the empire.’

The logic moves from ruler to minister, from noble to commoner, from family head to servant – always rooted in care, attention, and reciprocity. Such reverence bound people together, allowing the entire social fabric to function smoothly. The result? An empire described as peaceful (he), free of strife, immune to natural and man-made disaster.

Confucius is quoted at length here to underline his disdain for impersonal structures and his trust in emotional enablers: reverence, wholehearted participation, and attentiveness to those in one’s care. Relationships are central to his thought, and these emotional ties soften hierarchy. The emphasis is on practice, not the abstraction of theory.

This contrast is not just historical or philosophical – it points to a fundamentally different way of thinking about social order: one in which function tempers structure, and where rationality and emotion coexist.

Conclusion: Two logics, one challenge

Let me offer two tentative conclusions.

First, the Western obsession with theory – underpinned by a search for universal ‘truth’ – is not a necessity. Theory should help us understand reality, not obscure it. At its worst, theory elides emotional context and moral agency, offering necessity in place of responsibility.

Second, Sinic civilisation emphasises sufficient conditions, emotional intention, and personal responsibility. Action must be wholehearted, grounded in reverence and relational awareness.

Neither approach is flawless. Neither is inherently superior. That is the fate of the ‘crooked timber of humanity’. What matters is becoming aware of the differences – and using both stances in complementary ways. Whether that insight survives translation is uncertain. Western and Sinic cultures differ in deep and fundamental ways (see The Geography of Thought by Richard E. Nisbett). Becoming aware of the differences, and taking a step back from asserting culturally based ‘self-evident truths’, may be the first step to being able to converse and to learn from each other.

The post was first published on DeepDip.

Explore more of Aldo Matteucci’s insights on the Ask Aldo chatbot.

Click to show page navigation!