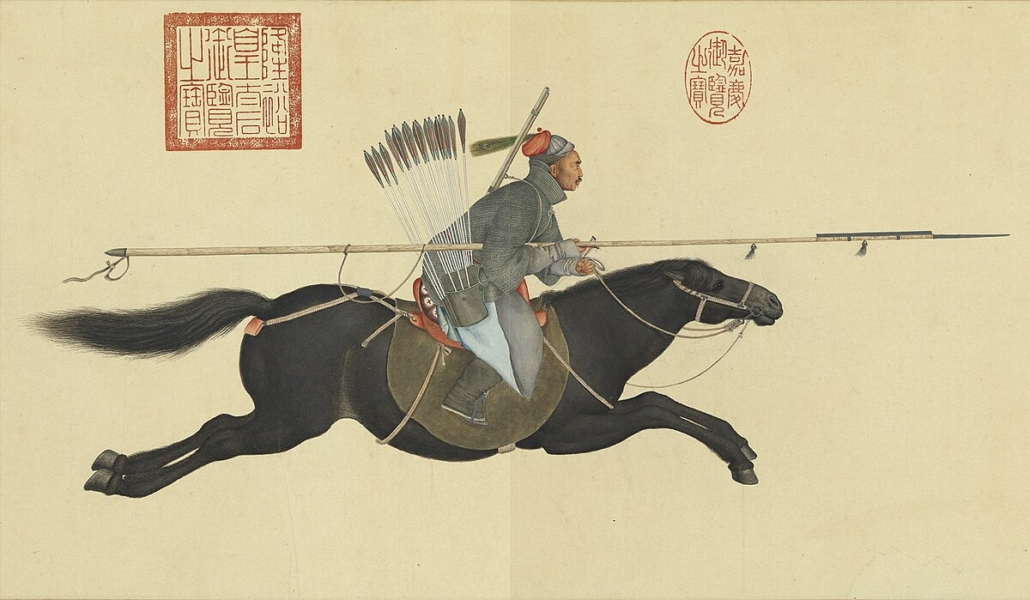

At the ‘border’ between nomadism and settled agriculture much exchange took place. Occasionally, however, nomads penetrated deep into settled country to raid and plunder (see The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, 221 BC to AD 1757 by Thomas J. Barfield; see The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians by Peter Heather). For the agriculturalist, the nomad coming ‘out of the blue’ was the ultimate scourge – the ‘other’, pillaging and killing. Defence was difficult: mobility and surprise were on the nomad’s side. Religion may have been the moral answer to the emergence of long-distance warfare on horseback, which left victims in its wake. Nomadic warfare and non-local religions are co-terminous (see Die großen Philosophen by Carl Jaspers).

This fear was worldwide. The Greeks spoke of the ‘barbarian’. In Chinese thought, hua had its negative counterpart in i, or barbarian (see The Great Wall of China: From History to Myth by Arthur Waldron).

Settled states developed many strategies:

- Trade and diplomacy (see Old World Encounters by Jerry H. Bentley)

- Indirect control through client states (see The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire by Edward N. Luttwak)

- Attempted conquest (see The Art of Not Being Governed by James C. Scott)

- Isolation (see The Great Wall: China Against the World 1000 BC–AD 2000 by Julia Lovell)

These strategies worked for a time, but centralised control overburdened settled states. Sooner or later the nomads struck.

The settler’s primeval fear of the ‘other’ – the elusive nomad – lives on today. Carl Schmitt argued that ‘morality is defined by good/evil, economics by profit/loss, aesthetics by beauty/ugliness. Politics is defined by friend/enemy’ (see Leo Strauss and the Politics of American Empire by Anne Norton). Leo Strauss carried this worldview to the USA, influencing neo-con advisors to President George W. Bush. His language was redolent of Wild West imagery – or worse (see At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America by Philip Dray).

The Ming dynasty illustrates the danger: ‘The basic problem was an inability to compromise, even over decades during which a high military cost was being paid for inflexibility. To the extent that the Great Wall is itself a product of this inability, it sums up one major continuity in Chinese foreign policy. The failure to reconcile pragmatic and idealised visions of the world, and the tendency to inject morality into political controversies, are enduring characteristics’ (see The Great Wall of China: From History to Myth by Arthur Waldron). After intrigue had doomed all other policies, the Wall – burdensome and futile – became the only consensual option.

Enablers, like horsemanship, open new ways of doing things. They create infinite possibilities. Once one path is chosen, alternatives fade and the chosen path feels inevitable. Enablers may arise through chance, curiosity, or emulation. They do not require visions or beliefs, but may lead to them afterwards. Such visions may be no more than fabulations from evidence. This is how human consciousness works, so we must take fabulation into account (see Who’s in Charge? Free Will and the Science of the Brain by Michael R. Gazzaniga). Visions and values may stabilise action, creating path-dependent outcomes.

What to do with enablers? We can pragmatically adapt to the differentiation they introduce. Or, like imperial China, we may inject morality into policy, clinging to ideals rather than compromise. As a friend quipped: ‘Moralism is what one does when no longer able to sin.’ Might this also apply to policy – and international policy?

The post was first published on DeepDip.

Explore more of Aldo Matteucci’s insights on the Ask Aldo chatbot.