Free trade and sailors’ rights: An 1812 diplomatic ’embarrassment’

Updated on 05 April 2024

The first US war of choice was the US-UK war of 1812-1814[1]. It ended with the Treaty of Ghent, signed on 24 December 1814. It ended not as the result of military victory or principled resolution of the issue: the defeat of Napoleon changed the context in decisive ways and rescued diplomats from their quandary. For the war was the result of diplomatic embarrassment.

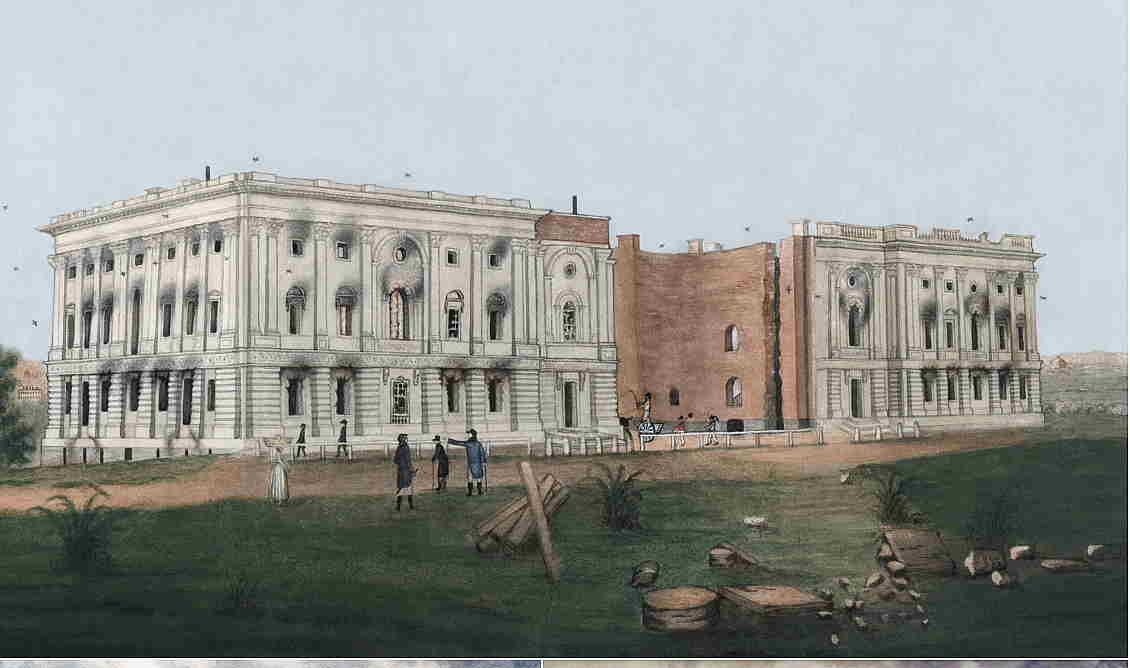

(British forces burned the White House)

Two issues in particular, on which the conciliation could not be found, precipitated the war.

Neutrality vs. sanctions

Britain and France were at war. Both sides resorted to economic warfare – trade with the enemy was prohibited. Neutrals – like the US – were enjoined to respect it by abstaining both from trade and contraband. The United States’ view was that Britain’s restrictions violated its right to trade with whomever it wished.

Economic sanctions are effective only if they are universal. This material fact inevitably forces neutral countries to “take sides”.

As the case of Iran shows, the issue is still unresolved today. After WWII neutral Switzerland was enjoined not to trade with the Communist Block. A compromise was found in voluntary compliance resp. limiting trade to the “courant normal” – verifiable assurances that Switzerland would not become a conduit for contraband. We have not progressed much beyond this point.

There is of course, a further option. In 1807–1808, President Jefferson and Secretary of State Madison even resorted to the drastic step of prohibiting all Americans from engaging in any form of international trade in order to stop France and Britain from fighting: “This embargo, said Jefferson, was a grand liberal experiment in “peaceful coercion” that if effective might do away with the instrument of war altogether and usher in an enlightened era of universal peace. (…) Although the embargo destroyed America’s overseas trade and devastated the country’s seaports, Jefferson and Madison persisted in its enforcement for fifteen months, even to the point of virtually warring against their own citizens.” [2]

Impressment of “American” sailors

The British had a problem: British sailors deserted and joined the American merchant marine. The British Admiralty estimated that as many as 10 to 15 percent of the 145,000 seamen in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars deserted to the American merchant marine – and a majority were mostly personally and politically disaffected Irish.

Britain did not recognize the right of a British subject to relinquish his citizenship, emigrate and transfer his national allegiance as a naturalized citizen to any other country (and in any case many naturalization papers at the time were forgeries).

Might is right

The British did not waste much time arguing the fine points of international law. They did it – blockading US harbors and searching ships. War ensued.

The British claimed emergency powers: they had not much of a legal case. By then the “right to trade” was well established. “Freedom of the seas” was also well established – in fact Britain had much fought over it in the past.

British behavior that led to war was a good example of extra-territorial application of national policies. Coercion of uninvolved countries into abiding by policies of warring parties was – in emergent principle – against the “spirit of Westphalia”, which, in the case of the Swiss Confederation, had acknowledged its neutral status. It helped that Switzerland was small, and all countries had equivalent interest in its becoming neutral.

Not all issues can be adjudicated

Circumstances rescued both sides from the diplomatic embarrassment. Neither side could win militarily, so the military option proved futile. And Napoleon, the cause of the disturbance, had been defeated.

Far from seeing this historical anecdote as an “embarrassment”, I find this humbling lesson reassuring. We need not be “right” in order to seek peace. Some issues are best left unresolved in principle.

[2] Gordon S. WOOD (2012): Mr. Madison’s weird war. New York Review of Books, June 21st.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!