The telegraph: How it changed diplomacy

Visit the other stops on our journey:

The period between the end of Renaissance diplomacy (early 16th century) and the start of the golden age of diplomacy and technology (early 18th century) was shaped by the Reformation and religious wars. Central Europe came out divided, while around it, new, more centralised states appeared, such as France, England, and Austria.

In this intermediate period, we focus on two remarkable personalities who made a long-lasting impact on diplomacy – Hugo Grotius and Cardinal Richelieu, and one important event – the Peace of Westphalia.

By the 16th century, the Christian Commonwealth had disappeared. Without the key roles of the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor as the ultimate arbiters in international conflicts, there were conceptual gaps in international affairs.

The Dutch philosopher Hugo Grotius was the first to offer a comprehensive concept that would overcome these gaps. Namely, he introduced schools of natural law and international law. According to Grotius, we – as individuals – have natural rights in order to protect ourselves. We are entitled to these natural rights as human beings. Through natural law, Grotius tried to establish a minimum moral consensus that could help society build itself and overcome the divisions of the escalating religious conflicts. Grotius started developing this approach with the idea that individuals, empowered by natural rights, are sovereign, and sovereign people create sovereign nations (opposing the existing idea that sovereignty is a divine right given to kings).

On this foundation, he developed the first theory of international law in his work On the Law of War and Peace (De Jure Belli ac Pacis) in 1625. Another book by Grotius also had a lasting impact in the field of international law, namely The Free Seas (Mare Liberum), where he formulated the new principle that the sea was an international territory and that all nations were free to use it for seafaring trade. As we will see, the teachings of Grotius influenced the construction of the Peace of Westphalia. The Grotius notion of the sovereignty of individuals has been re-emerging in discussions around the sovereignty of personal data.

The French statesman Cardinal Richelieu was another person whose legacy remains until today. He developed the idea of diplomacy as a continuous process and permanent activity. The idea of the permanence of diplomacy started developing during the Renaissance, with the introduction of permanent ambassadors. It took full form in the time of Richelieu. Institutionally, in 1626, Richelieu established the first modern ministry of foreign affairs in, more or less, the same format we know today.

Richelieu also argued that diplomacy should be governed by raison d'êtat (national interest). The interests of the state are primary and eternal. They are above sentiments, prejudice, and ideologies.

Richelieu was also the main architect of the expansion of French diplomacy. By the 18th century, the French language had become the lingua franca of diplomacy, and has remained so until recently.

Peace of Westphalia

ʻWestphaliaʼ is probably one of the most frequently used historical references in modern international relations and politics. The Peace of Westphalia is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. These two documents ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peace to the Holy Roman Empire, closing a period of European history when approximately eight million people were killed.

The Swearing of the Oath of Ratification of the Treaty of Münster.

Source: Encyclopædia Britannica.

The Peace of Westphalia established the sovereignty of states as independent political units. The system based on nation states replaced the one based on the ultimate sovereignty of the Roman Catholic Pope and the Holy Roman Empire.

The Westphalia peace negotiations began after all sides in the war were exhausted by 30 years of fighting and destruction. Ultimately, they reached a compromise which did not satisfy anyone (a good basis for compromise). The peace deal was the result of very long negotiations that lasted 4 years. The first 6 months were dedicated to agreeing on the question of precedence, which was highly controversial due to the participation of 200 rulers and more than 1,000 diplomats.

ʻWestphaliaʼ was a milestone event marking the beginning of the modern era and the sovereign states which have lasted until today.

Congress of Vienna (1814/1815)

The 18th century was a period when European diplomacy tried hard to maintain a balance between five great powers: Britain, France, Austria, Russia, and Prussia. The French Revolution and the attempts of Napoleon I to conquer Europe have shaken the continent's state system and paved the way for the Congress of Vienna (1814/1815).

The Congress was one of the biggest events in the history of diplomacy and laid the basis for a peace that lasted almost 100 years. It was organised in quite a relaxed atmosphere, and included salons, banquets, balls, and an exceptional cuisine. Austrians paid great attention to the social aspects of the event.

Congress of Vienna, August Friedrich Andreas Campe

Source: Encyclopædia Britannica

Two personalities marked the Vienna Congress: Prince de Talleyrand, French minister of foreign affairs, and Klemens von Metternich, Austrian minister of foreign affairs. They were the key shapers of the peace deal.

The peace talks were organised in order to deal with Europe after the Napoleonic Wars, and Talleyrand managed the impossible. Despite being on the losing side, he managed to influence the outcome of the negotiations, and proved an able negotiator for the defeated France. Simultaneously, Metternich brilliantly mastered his dual role of social representation and political leadership. His moderation of the Congress produced a long-lasting European order.

The Final Act of the Congress of Vienna comprised all the agreements in one great instrument. It was signed on 9 June, 1815. The Congress of Vienna survived the test of time – 100 years without a major global war, up until the outbreak of the First World War.

The invention of the telegraph

The 19th century was also an era of great scientific and technological breakthroughs, with the telegraph being the most important invention for diplomacy.

The word ‘telegraph’ derives from the Greek words 'têle' (‘at a distance’) and 'gráphein' (‘to write’). A variety of other terms were used for the telegraph, among others 'tachygraph' from the Greek word ‘tachos’ (‘speed’), highlighting the temporal aspect of communication. Arguments over the naming of this new device centered around its spatial vs temporal impact. Spatial impact prevailed and we got 'telegraph' instead of 'tachygraph'.

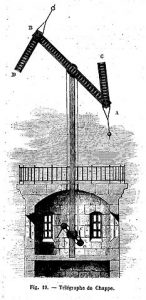

The first mechanical telegraph (the semaphore) was invented in 1792 in France by Claude Chappe. It consisted of towers built in a line across the countryside. To facilitate the message transmission, Chappe developed a code book of 92 symbols. For that time, the communication speed was incredible as the message could be transmitted from Paris to Lille (a distance of 230 km) in 10 minutes. This system was invented during the French Revolution and was used in the Napoleonic Wars (1789–1815).

By 1844, France had some 5,000 km of semaphore communication lines used mainly by the military. The only civilian use of the telegraph was for the national lottery, which, coincidentally, was also a good source of revenue for the running of the telegraph system.

Great Britain and Germany also developed mechanical telegraph systems, again, mainly for military use.

We can make one historical parallel here between Chappe’s mechanical telegraph and ‘Minitel', a French predecessor of the internet. Similarly, the two inventions gave France a slight advantage, but France missed the opportunity to capitalise on it. The mechanical telegraph was run over by the electrical one, and Minitel was replaced by the internet.

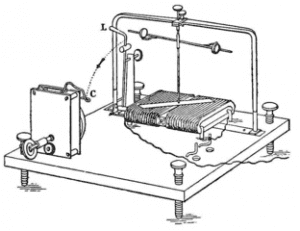

The invention of the electric telegraph was more a process than a moment of creative illumination, and different countries claim credit for the invention.

The electric telegraph is often called the 'internet of the 19th century' or 'the Victorian internet'. as Tom Standage wrote in his book The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century's On-Line Pioneers. As the English historian Robert Sabine described this process, 'The electric telegraph did not, strictly speaking, have an inventor. It grew little by little towards perfection, with each inventor adding his bit.'

Some of these additions are listed below.

- The functional principle of transmitting a message over distance was introduced by the semaphore, i.e. Chappe’s 'mechanical' telegraph in 1792.

- Electric batteries, invented by the Italian Volta in 1800, were an important pre-invention.

- The German physicist Sömmerring experimented with electrochemical reactions and some proto-versions of the telegraph.

- In 1820, Ampère conceptualised a needle-telegraph device.

- An important step in the process of the invention of the electric telegraph was the work of the Russian diplomat Baron Pavel Schilling. During his posting in Germany, Schilling developed an electric telegraph in 1832. His invention was successfully tested in St Petersburg where, via the electric telegraph, he connected a number of buildings of the Russian Chief Admiralty.

- In Britain, Cooke and Wheatstone were the first to use the telegraph in 1838 for commercial purposes by establishing a more efficient communication among the growing network of railway lines. As all the trains used the same railway lines, the exact location of each train was of the utmost importance for the normal functioning of the system. Telegraphy then spread quickly to other commercial activities, including the support of trade and financial transactions.

- In 1844, Samuel Morse (who was incorrectly credited as the inventor of the telegraph) settled the first telegraph line between Washington and Baltimore. Morseʼs main contribution to telegraphy was the invention of a special code, named the Morse Code after him, for exchanging text messages via telegraph lines.

From1858 to 1866, there were various attempts to lay a transatlantic cable which resulted in establishing a fully reliable link in 1866. After this, the New York and London stock exchanges became linked and frequently exchanged information. This boosted economic activities enormously.

Changes in diplomatic activities

The telegraph affected the distribution of power. Prior to the introduction of the telegraph, the big banking family Rothschild developed a communication system based on couriers and carrier pigeons which connected the main European economic centres. This gave them a competitive advantage which disappeared with the introduction of the telegraph. James de Rothschild once said that 'it was a crying shame that the telegraph has been established'.

One of the unforeseen consequences of the telegraph was the impact it had on the emancipation of women, as they were often employed as telegraph operators. With secure jobs, greater rights, and the possibility of education, women in industrialised countries started getting more important positions.

Techno optimism: The former British ambassador Edward Thornton wrote: ‘Steam was the first olive branch offered to us by science. Then came a still more effective olive branch - this wonderful electric telegraph, which enables every man who happens to be within reach of a wire, to communicate instantaneously with his fellow man all over the world.’

Techno scepticism: Some rulers were cautious of the potential social impact the telegraph might bring. For example, the Russian Tsar Nicolas I considered the telegraph to be 'subversive'. Afraid of its potential to disseminate information, he declined an offer by Morse to develop the countryʼs first telegraph lines. As a result, Russia lagged greatly behind other major powers.

Cable geostrategy: The control of telegraph cables became of crucial geostrategic importance. The control of the telegraph meant the control of information, an important element of power. Additionally, big powers laid cables in order to create their own global telecommunications infrastructures. Until the 1880s, the 'cable rush' was mainly inspired by commercial and telecommunications needs.

Towards the end of the century, Great Britain controlled most of the global telegraph network. A number of reasons led to Britain's dominant position:

- It started laying submarine cables in order to facilitate communication with its remote colonies, mainly India.

- Its control of the seas helped Britain to lay submarine telegraph cables without any major obstacles.

- The high cost of developing and maintaining its telegraph network was partly compensated by commercial traffic, since the main strategic telegraph outposts coincided with the main trade routes (Gibraltar, Malta, Cyprus, Alexandria, Aden, Singapore, Hong Kong, etc.).

Britain established a starting advantage that was difficult for many countries to reach in the forthcoming decades. Other countries realised relatively late both the importance of having a telegraph network and the extent of the British dominance.

Although France pioneered the development of the telegraph, it was a latecomer in the development of a global telegraph cable network. It was only after a series of crises (Tonkin, Siam, Fashoda) that the French started taking seriously the lack of a telegraph network and the British dominance.

During the 1898 Fashoda Incident in Africa, French plans to control Africa from the west (Dakar) to the east (Djibouti) clashed with the British ambitions to establish a north–south control over the continent, from Cairo to Cape Town.

Two colonial projects collided in Fashoda, a small village in present-day Sudan. Even though France had an advantage on the field, it didn’t have the means to communicate this to its headquarters. On the other hand, the British conveyed false information to London about the difficult position of the French troops in Fashoda. The technological advantage was so strong that the French officials were forced to ask their British counterparts to send a message to Paris via the British telegraph.

After this crisis, France and Germany realised that they have to close the 'cable gap' and started developing their own global cable networks.

The United States started to emerge as a global political and economic power, which could be seen in the extent of its global cable network. Unsuccessful attempts to establish a transatlantic link are often cited as one of the reasons that the USA purchased Alaska, then known as Russian America. Faced with difficulties in establishing a transatlantic link, the Western Union president Hiram Sibley urged the purchase of Alaska in order to establish a 16,000 mile land-based wire between the USA and Europe. This terrestrial telegraph scheme was abandoned in 1868 when the transatlantic cable proved to be a success. Alaska, though, remained part of the United States.

The telegraph gradually became part of international negotiations and diplomatic tactics.

A new topic on the diplomatic agendas

The telegraph appeared early on the diplomatic agendas. In the mid-19th century, the first international agreements were signed in order to manage telegraph communication.

The most developed network of bilateral agreements took place in Germany which was at the time divided into many small states. In 1849, Prussia and Saxony concluded the first bilateral agreement and others followed. Only one year later, the German states and Austria established the Austro-German Telegraph Union (AGTU).

Other European countries started concluding bilateral agreements which led to the establishment of the West European Telegraph Union (WETU) in 1855, a regional organisation that included Belgium, France, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and Switzerland. Other countries subsequently joined WETU.

In the end, bilateral arrangements could not keep pace with the intensity of technological developments. The need for a comprehensive multilateral arrangement was obvious, and the first multilateral arrangement was adopted in 1865 in Paris with the establishment of the International Telegraph Union (ITU).

In 1868, the International Bureau of Telegraph Administration was established in Bern, which is considered to be the first permanent international organisation.

One of the main international legal issues raised in 1865 at the International Telegraph Conference held in Paris, was the neutral status of submarine telegraph cables. France, later joined by Germany and other states, requested the protection of submarine telegraph cables in case of war. The main opponent was Great Britain since it both controlled most submarine cables and the technology for managing them (including cable-cutting tools). At the end, cables remained outside the regulations covering the conduct of war.

Many important political decisions which influenced the future development of the telegraph were adopted at the next diplomatic conference, the International Telegraph Convention of St Petersburg, in 1875. One of the most controversial issues was the control of the content of telegraph communication. While conference participants from the USA and the UK promoted the principle of the privacy of telegraph correspondence, Russia and Germany insisted on limiting this privacy in order to protect state security, public order, and public morality. A compromise was reached through an age-old diplomatic technique: diplomatic ambiguity.

While Article 2 of the St Petersburg Convention guaranteed the privacy of telegraph communication, Article 7 limited this privacy and introduced the possibility of state censorship. The United States, which did not participate, refused to sign the convention because of 'the censorship article'.

The introduction of new topics on diplomatic agendas influenced the organisation of diplomatic services and led to the emergence of new posts in diplomatic missions, such as military attachés, as well as diplomats in charge of economic and cultural affairs.

The use of new tools in diplomacy

It was in the 1850s that the telegraph started to be used as a tool in diplomatic services. The telegraph was initially used in diplomacy for internal communication between diplomatic missions and headquarters. This also included communication regarding personal, ceremonial, and organisational matters. During the Congress of Paris (1856), British representatives received instructions from prime minister Palmerstone through coded telegrams.

In 1866, the US State Department sent a cable to the US Mission in Paris. The encrypted message that passed through British and French cables did not prove to have any diplomatic importance, but it did go down in the history of diplomacy and technology as one of the most expensive tech experiments in diplomacy. The cost of the dispatch of this telegram was US$20,000, while the total annual budget of the US State Department at the time was US$150,000. This huge bill triggered a court case between the State Department and the telegraph company. Eventually, after the decision of the Supreme Court, the US government was forced to pay for this expensive diplomatic experiment.

By the end of the 19th century, the telegraph was being used in day-to-day diplomatic activities, triggering mixed reactions. The British ambassador to Venice, Sir Horace Rumbold, commented on the negative impact of the telegraph on the independence of diplomats in their function: 'the telegraphic demoralisation of those who formerly had to act for themselves and are now content to be at the end of the wire'. Diplomats also frequently complained about the lack of time for a proper and analytical approach to diplomatic activities.

The telegraph also became part of diplomatic tactics. Three telegrams had a considerable impact on the development of international relations and, to a certain extent, changed the course of history:

- The Ems Telegram is usually considered to be an example of how technology could be used for achieving strategic and military objectives. In the 1870s, Bismarckʼs objective was to unify Germany, and his first step was to start a war with France. How did a dispatch help Bismarck achieve his aim? In a time of crisis in the relations between France and Prussia, the Prussian king, who was not very keen on starting a war with France, sent Bismarck a telegram from Ems in which he reported on his meeting with the French ambassador and asked Bismarck to inform the diplomatic corps and press. Bismarck shortened the original telegram and forwarded it to the French, which provoked a war and led to German unification of 1871.

- The Zimmerman Telegram became part of history because it influenced the USA to abandon its neutrality and enter World War I in 1916. The telegram was sent by the German foreign minister to the German ambassador in Mexico, allegedly asking him to offer Mexico parts of California and Texas in exchange for Mexico, thereby joining Germany in the war. The telegram was intercepted by British intelligence and rewritten in such a way as to provoke a strong anti-neutrality sentiment in the USA. This ultimate goal was achieved and the USA entered the war.

- The July Crisis telegram was sent during the July Crisis of 1914 just before the start of WW I. The major problem, which led to the failure of diplomacy, was the diplomatsʼ inability to cope with the volume and speed of electronic communication. As Prof. Stephen Kern noted: 'This telegraphic exchange at the highest level dramatised the spectacular failure of diplomacy, to which telegraphy contributed with crossed messages, delays, sudden surprises, and unpredictable timing.' Diplomats 'failed to understand the full impact of instantaneous communication without the ameliorating effect of delay'.

The important rationale for the July Crisis example is that speed and immediacy do not necessarily provide positive results. On the contrary, it is likely that they can lead to reckless moves and miscommunications.

The most important aspects of the telegraph

The need for urgent replies

The speed of message transfer has been linked to urgency. If a message travels for months, one can afford time to prepare a proper response. This situation changed with the telegraph. The immediacy of sending back messages required immediate responses from diplomats abroad. This led towards potential hasty and, sometimes, not properly prepared responses.

The problem of coordinating communication

Urgency led towards the problem of coordinating communication. Very often, telegrams would arrive in the wrong order, creating considerable confusion with serious consequences, as was the case prior to the First World War: During a delicate exchange on the Alabama dispute, the US foreign secretary Granville warned the British prime minister Gladstone of this risk: 'This telegraphing work is despairing. It will be a mercy if we do not get into some confusion.'

The need to prepare concise messages

The telegraph was an expensive medium, so the content of each telegram had to be carefully considered. Diplomats had to improve the quality of diplomatic reportage. They had to abandon long and descriptive memos and master the skill of concise and precise writing. The telegraph is a good example of how technology influenced style and etiquette.

The emergence of foreign policy bureaucracy

Although the first ministries of foreign affairs were established earlier, their number increased at the end of the 19th century as a result of bureaucratic expansion.

French diplomacy grew from 70 diplomats in 1814 to 170 diplomats a century later. The Habsburg Empire had 51 diplomats in the mid-19th century and 146 in 1918. Foreign ministries achieved the shape that they, more or less, retained until today: they mainly consisted of geographical departments handling bilateral relations with various countries; entrance exams gradually replaced family ties as the main recruitment method; new diplomats were trained in diplomatic academies; and a sense of professionalism started to prevail.

The centralisation of diplomacy

Easier communication via the telegraph and well-equipped ministries led to the centralisation of diplomatic services. Previously independent diplomatic missions came under the control of their headquarters, and instructions could easily be sent via the telegraph.

1814–1914: Statesmen (from leaders to followers)

Statesmen and diplomats were essentially unprepared for the sudden appearance of this new technology which overwhelmed them and contributed to the fact that they ceased to be the creators of policies and became mere followers of events which were getting out of their control. Unprepared to handle the new technology, diplomats who used to meet and manage international peace through direct communication suddenly became involved in the frenetic world of 'modern diplomacy' conducted via telegraphs and telephones.

The period after the Vienna Congress was decisive for diplomatic developments, and was heavily influenced by technology (the telegraph and telephone). In this period, the basis was laid for the diplomacy we have today: embassies, ministries, communication, and diplomatic reporting. By studying this period we can learn how not to repeat the same mistakes and how to create more optimal solutions for potential confusions and conflicts.

Meanwhile in … China

The first telegraph lines in China were established during the 1860s when imperial powers used them to connect with their colonies to Europe. The government of the Qing dynasty was initially very reluctant about establishing their own telegraphic lines fearing that they might be used by the European powers. The first Chinese line was established in 1871 from Hong Kong to Shanghai by Denmark’s Great Northern Telegraph Company. This also meant an introduction of the telegraphic code for Chinese which greatly differed from the alphabet code. A few years later, the Chinese built themselves a line mainly used for military purposes. In 1876 China’s first telegraph school was opened. Its students learned how to operate, but also how to construct telegraphs and how to lay its lines. In this way China secured an educated class of telegraph operators.

In 1881 the government established the Imperial Chinese Telegraph Administration (ICTA) that took control over all existing networks in the country, save the foreign ones. By 1900, it had 14,000 miles of telegraph lines connecting all the cities along the coast. However, its prices were high and delays in transmission frequent so it did not have such a deep impact on Chinese society as it did in many other countries.

Cheers! Champagne

Champagne, the celebration drink, was named after the Champagne region in northeast France where the drink is made.

This sparkling wine was discovered by accident. The cold Champagne winters stopped fermentation, and when the yeast cells awoke again in spring, the released carbon dioxide caused the bottles to explode. Monks, who were the winemakers, thought that they were ‘possessed’ and called champagne ‘the wine of the devil’ (‘le vin du diable’).

Another story tells that champagne was invented by the monk Dom Pérignon. This was later proven wrong as documents showed that an Englishman had already produced it. At first, Perignon tried to eliminate the bubbles from the wine but without any success. Since he couldn't fight it, Pérignon decided to try to perfect the art, and he is today credited as the inventor of champagne. When he tasted champagne for the first time, he exclaimed, ’Come quickly, I am drinking the stars!’

Reims, the capital of the Champagne region, became the official location for crowning incoming French kings from the 9th century, and the wines used during the coronation were champagne wines. By the 18th century, champagne was so established that it was the only wine served at the Fête de la Fédération festival held in July 1790 to celebrate the French Revolution.

One of the important traditions related to champagne is its use during ship launchings. This so-called ‘christening’ ceremony is performed by breaking a sacrificial champagne bottle over the bow as the ship is launched. A maritime superstition held that a ship that wasn’t properly christened would be unlucky, and a champagne bottle that didn't break was a particularly bad omen.

The love of champagne also united the European powers at the Congress of Vienna in 1814/1815. During the nine months of negotiations, delegates enjoyed the finest champagne wines. It is said that Lord Richard Lyons, British ambassador to Paris, offered at least five courses of Moet and Chandon champagne at his diplomatic dinners because he found it made the US senators more flexible. He is famous for his quote: ‘If you're given champagne at lunch, there's a catch somewhere.’

Since the 19th century, champagne wines have been fashionable at royal weddings and every other great ceremony. In 1889, and again in 1900, champagne was served at the World’s Fairs in Brussels and Paris.

Watch the recording of our August Masterclass The telegraph: How it changed diplomacy. Consult the PPT presentation.

Recordings from all sessions are available on our YouTube channel.

The telegraph and diplomacy [An interview with Tom Standage]

This month, Dr Kurbalija interviewed journalist and author Tom Standage to talk about the impact that the invention of the telegraph had on the geopolitics of the time.

Standage is deputy editor of The Economist and is responsible for the newspaper’s digital strategy and the development of new digital products. He is the author of six history books, including Writing on the Wall: Social Media — The First 2,000 Years, the New York Times bestseller A History of the World in 6 Glasses (2005), and The Victorian Internet (1998) on the history of the telegraph.

For more information on this topic, you can consult the following resources:

The Rise of Modern Diplomacy 1450-1919,

Author: M.S. Anderson (1993) Longman

Though international relations and the rise and fall of European states are widely studied, little is available to students and non-specialists on the origins, development and operation of the diplomatic system through which these relations were conducted and regulated. Similarly neglected are the larger ideas and aspirations of international diplomacy that gradually emerged from its immediate functions.

This impressive survey, written by one of our most experienced international historians, and covering the 500 years in which European diplomacy was largely a world to itself, triumphantly fills that gap.

Dynamics of Modern Communication: The Shaping and Impact of New Telecommunication Technologies

Author: Patrice Flichy (1995) Sage Publications, London

Combining political economy with the sociology of innovation, Dynamics of Modern Communication is a comprehensive social history of communication technology from 1790 to the present. Author Patrice Flichy presents a careful critique and historical analysis of the social shaping and impact of the major communication technologies of the past 200 years. From the semaphore and telegraph to contemporary information technologies like the phonograph, photograph, telephone, radio, cinema, and television, this book focuses on the relationship between technological change and the social changes in which they were situated. Particular emphasis is put on four social processes: the birth of the modern state at the end of the 18th century, the development of stock markets, the transformation of private life in the modern nuclear family, and the individualism of the late 20th century.

Servants of Diplomacy, A Domestic History of the Victorian Foreign Office

Author: Keith Hamilton (2021) Bloomsbury publishing

Servants of Diplomacy offers a bottom-up history of the 19th century foreign office and in doing so, provides a ground-breaking study of modern British diplomacy. Whilst current literature focuses on the higher echelons of the Office, Keith Hamilton sheds a new light on the administrative and social history of Whitehall which have, until now, been largely ignored.

Hamilton’s examination of the roles and actions of the Foreign Office’s domestic staff is exhaustive, with close attention paid to: the keepers of the office, keepers of the papers, the carriers of the papers and the efforts made to adapt to growing technological changes. Hamilton’s exhaustive analysis also focuses on the reforms of 1905-06 and the Queen’s Messengers during wartime.

Drawing extensively from Foreign Office and Treasury archives and private manuscript collections, this is essential reading for anyone with an interest of British diplomatic history

The Electric Telegraph

Author: Robert Sabine, (2012), HardPress Publishing

The work is divided into Two Parts: the First being confined to a short history of the Electric Telegraph, and descriptions of many of the past and existing methods and apparatus; the Second Part being confined exclusively to the more scientific matter relating especially to Cable York.

Mapping World Communication (War, Progress, Culture),

Author: Armand Mattelard; translated from the French by Susan Emmanuel and James A. Cohen (1994), University of Minnesota Press

With the trenchant wit and keen insight that have earned him international acclaim, Armand Mattelart offers a history of modern communications that exposes the connection between militarism and the evolution of the media industry, while questioning the notion that technological innovation is always synonymous with progress. The history of modern media emerges in this account largely as a history of state control, wielded to discipline internal populations and combat external enemies.

With dazzling detail, Mattelart moves from the rise of the postal stamp to international telegraphy to the world press, and finds in each the hand of state strategy.

The American Leonardo: A Life of Samuel F.B. Morse.

Author: Mabee Carleton, (Purple Mountain Pr Ltd, New York)

This new edition of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography (originally published in 1943 by Alfred A. Knopf) describes the life and career of Morse, with attention to his artistic achievements, his inventions, his faith, and the contradictions of his character. This edition features color reproductions of some of Morse's paintings. Mabee is professor emeritus of history at State University of New York in New Paltz.

The Media's Impact on International Affairs: Then and Now

Author: Neuman, Johanna, (1996), The Johns Hopkins University Press

This paper argues, in contrast, that satellite television, and the coming clashes in cyberspace, are but the latest intrusions of media technology on the body politic. Throughout history, whenever the political world has intersected with a new media technology, the resulting clash has provoked a test of leadership before the lessons learned were absorbed into the mainstream of politics. Eventually, the turmoil caused by a new media technology's impact on diplomacy is absorbed and forgotten, until the next media invention begins the process anew.

The Information Age: An Anthology of Its Impacts and Consequences.

Authors: David S. Alberts and Daniel S. Papp (eds.), (2012), CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

With the fall of communism in Eastern Europe and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Cold War ended, and the half-century-old bipolar international system disappeared. These were earthshaking events that rightly received and are receiving extensive study and analysis. They occurred for a host of reasons, many of which were related to the internal political, economic, social, and cultural dynamics of communist states. Several of the more important reasons were the resentment of citizens of communist states toward the institutions and individuals that governed them; a resurgence of nationalism within multinational states; the inability of communist states to transition successfully from centralized political, economic, and administrative structures to more decentralized structures; inadequate economic growth rates and declining standards of living; the inability of communist states to diffuse technical advances throughout productive sectors of society; and over-emphasis on defense spending.

The Victorian Internet,

Author: Tom Standage, (1998), London: Phoenix

The Victorian Internet tells the colorful story of the telegraph's creation and remarkable impact, and of the visionaries, oddballs, and eccentrics who pioneered it, from the eighteenth-century French scientist Jean-Antoine Nollet to Samuel F. B. Morse and Thomas Edison. The electric telegraph nullified distance and shrank the world quicker and further than ever before or since, and its story mirrors and predicts that of the Internet in numerous ways.